In 2023, we must take on the technocrats

We are being ruled by ‘experts’ who have failed us time and again.

Donate to spiked this Christmas, and help keep us free, fearless and independent.

Perhaps the only positive quality of the hapless Liz Truss and her short-lived 2022 premiership was her willingness to question the ‘orthodoxy’. In particular, she took issue with the obstinacy and failures of the institutions that oversee the British economy – from the Treasury and the Bank of England to the Office for Budget Responsibility. The great irony is that, after her brief free-market experiment crashed and burned last year, these very institutions and the technocratic outlook they embody became more powerful than ever. By the end of 2022, after an all-too-brief hiatus, technocracy had re-established itself as the driving force in British politics.

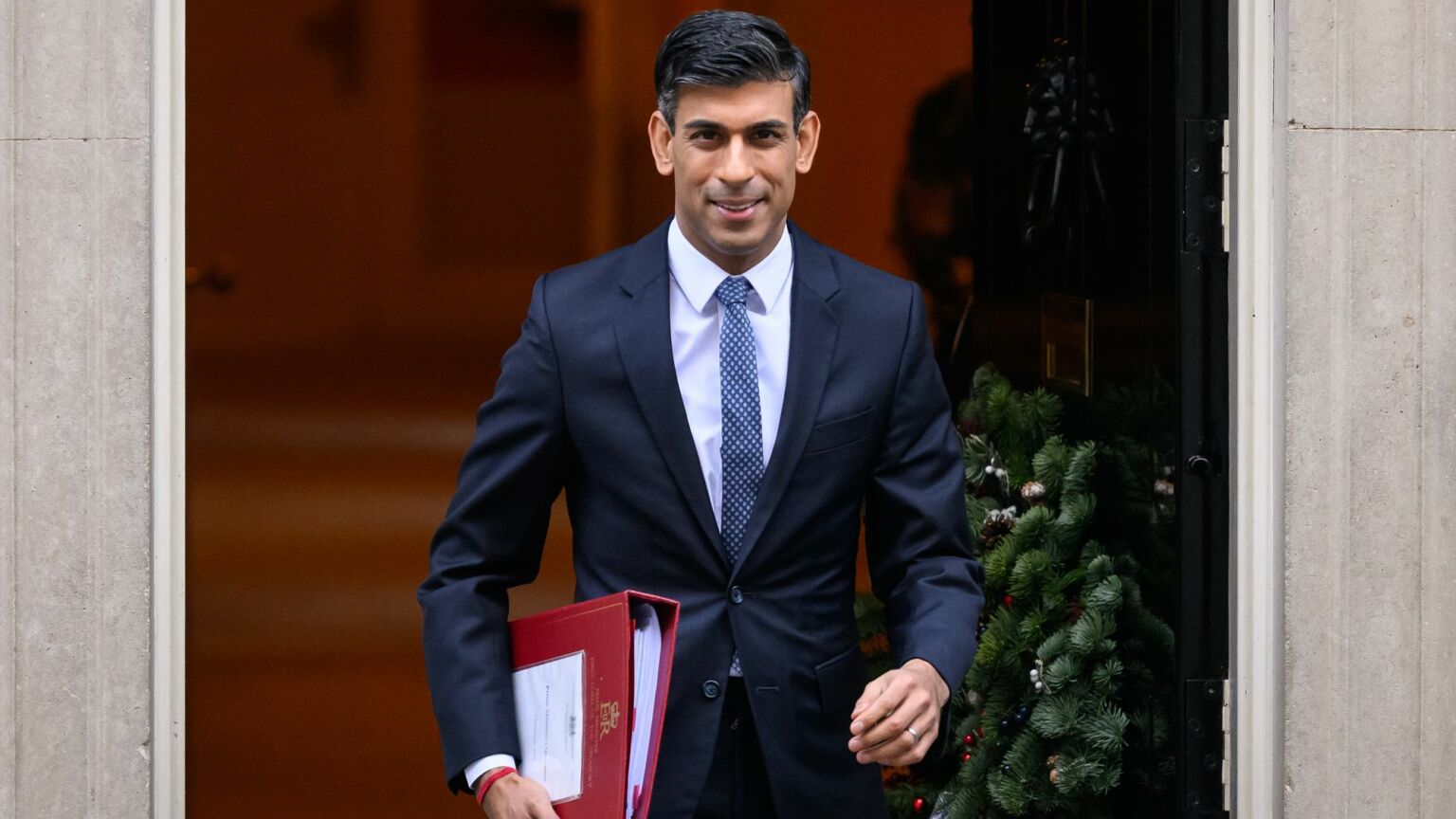

After the coronation of Rishi Sunak in the autumn, we were assured that the ‘adults’ were in charge again. Sunak’s government, with fellow technocrat Jeremy Hunt as chancellor, set out to contrast itself with its predecessors. It sought to signal an end not only to the market turmoil triggered by Truss, but also to the Tory Party’s flirtation with populism. It wanted to repudiate what Vote Leave’s Michael Gove famously argued during the 2016 Brexit referendum, that Britain has ‘had enough of experts… saying that they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong’. From now on, the government would once again defer to the alleged wisdom of the civil-service beancounters. And its policies would be tailored to placate the money markets, rather than the voters.

All of this was music to the ears of the establishment. Finally, we are going to get a government willing to ‘make politics boring again’, cheered one newspaper editorial at the time of Sunak’s coronation. And what was being celebrated across the media was not so much the prospect of calm being restored to the markets, but rather the restoration of ‘calm’ to politics. By which they meant the removal of debate and contestation from public life and the narrowing of possibilities for change. As former Tory leader William Hague wrote in The Times just before Truss’s resignation, ‘the idea that Britain can break out of the economic orthodoxy she derided… is dead’. This is the re-emergence of TINA – the assertion that ‘there is no alternative’ to what the technocrats are offering.

There is no doubt that Truss’s short tenure as PM was a calamity. Her so-called mini-budget was followed by a crash in the pound and bedlam in the bond markets, sending the cost of government borrowing skywards. But the response from the establishment was more than a little dishonest. Essentially, the Truss disaster was treated as a warning to anyone who might dare challenge the cosy economic consensus. By a clever sleight of hand, her policies of tax cuts and deregulation were portrayed by recalcitrant Remainers as the logical outcome of Brexit and of ‘populist’ thinking more broadly. This is what happens when you try to please the people, screamed the chorus of disapproval, despite her plans being backed by only a tiny segment of the public.

Just days after the mini-budget, the International Monetary Fund made an unprecedented intervention, calling on Truss to ‘re-evaluate’ (ie, reverse) her economic policies. Within weeks, the pressure became too much to bear and she sacked her chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, and replaced him with cold-blooded technocrat Jeremy Hunt. In a television broadcast to the nation, Hunt gutted Truss’s mini-budget, announcing the reversal of almost every planned measure. To placate the demands of the markets, the government had been lobotomised. With no authority left, unable to pursue her economic programme, Truss resigned.

The Sunak government that followed then gained power without any democratic input. Now, Truss didn’t have a democratic mandate, either. But at least she had to win over Tory Party members following a months-long public debate. Sunak, by contrast, was crowned by Tory MPs after Truss’s resignation in October. There was no vote by Tory members, let alone the wider electorate.

This lack of a mandate was actually celebrated by his supporters at the time. Former chancellor George Osborne said it was the ‘vote’ of the markets that really counted. Or as a Guardian column put it: ‘Sunak’s finest legacy will be not to have played to the electorate.’ Previous Tory leaders, the piece argued, were ‘hamstrung by the forces of grassroots populism, as expressed in the [Brexit] referendum, two General Elections and two leadership elections’. In other words, while Sunak’s policies may have been constrained by the demands of the market, at least he has freed himself from the demands of the electorate. Democracy has given way to technocracy.

As we enter 2023, we desperately need to cut the technocrats down to size. The great lie of technocracy is that the experts are best placed to make decisions in the national interest. That they somehow stand above the wayward passions of the electorate or the ideology of elected representatives. In reality, technocrats tend to simply pass off their own prejudices as superior insight.

What’s more, many of the worst crises that confront us today can be traced back to decisions made by or supported by our technocratic elites. Just recall how the government’s scientific experts pushed for the country to be shut down for nearly two years, leading to the worst fall in economic output in the history of modern capitalism. Or how the financial experts at the Bank of England agreed to pump almost half a trillion pounds into the economy, claiming that any inflation this might cause would be temporary. Or how the government’s climate and energy experts continue to push for Britain to wean itself off of reliable fossil fuels and to move towards unreliable renewable energy – a policy that has already hugely exacerbated the energy crisis.

The challenges of our times call for fresh and bold thinking, not plodding managerialism or discredited groupthink. What we need is for the public to be brought back into politics, not relegated to the sidelines or treated with suspicion. This year, we must take on the technocrats.

Fraser Myers is deputy editor at spiked and host of the spiked podcast. Follow him on Twitter: @FraserMyers

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.