How the Abedi brothers slipped through the net

The Manchester Arena bombers exploited our institutions’ blindness to Islamist extremism.

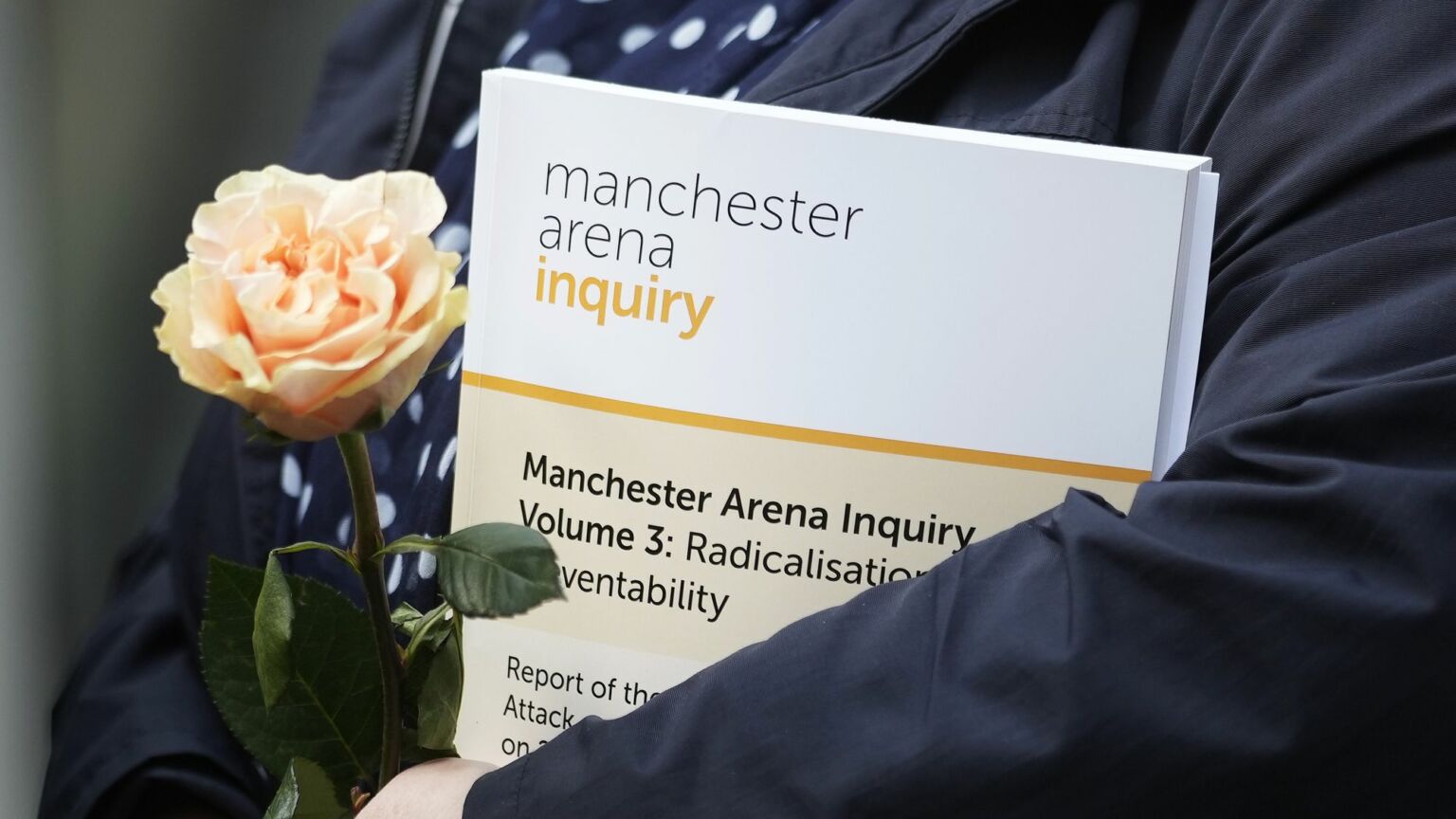

The inquiry into the Manchester Arena terror attack, chaired by Sir John Saunders, delivered its third and final report last Friday. The report reveals the mess Britain has got itself into over Islamist terrorism. And the consequences of ignoring the threat it poses.

Twenty-two people died when Salman Abedi detonated a suicide bomb as crowds left an Ariana Grande concert on 22 May 2017. Seventeen of those killed were female, eight were aged 18 or under. The youngest, Saffie-Rose Roussos, was just eight years old. In 2020, the bomber’s brother, Hashem Abedi, was convicted of murder for his part in assisting Salman and was jailed for 55 years. In prison, Hashem Abedi has continued to fraternise with other Islamist inmates and last year was one of three terrorists found guilty of assaulting a prison officer at HMP Belmarsh.

One issue raised by Saunders’ report is the inaction of the intelligence services. Salman and Hashem Abedi seemed to exhibit plenty of signs of radicalisation and yet were never adequately investigated.

The Abedi family had moved to Manchester in the early 1990s as exiles from Colonel Gaddafi’s Libya. The head of the family, Ramadan Abedi, was reportedly a supporter of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group. As with Islamic State, the clue as to the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group’s intentions was written clearly in its name. In the report, Saunders writes: ‘[Salman and Hashem Abedi’s] parents, particularly their father, held extremist views. The family circle in Libya included people who, at some time, were involved in terrorism.’

In September 2011, the Abedi family moved back to Libya, and there is evidence that Salman, then aged 16, fought in the civil war. He also returned to Libya again in 2014 to fight for an Islamist group.

Among the Abedi family’s friends was Abdalraouf Abdallah, another British Libyan from Manchester, who was seriously injured fighting in the February 17th Martyrs Brigade militia during the Libyan civil war. After returning to Britain, the wheelchair-bound Abdallah managed to get himself convicted of terrorist offences in the UK in 2016. Many reading Saunders’ report will not be able to understand how Abedi, who had spent time fighting alongside Islamists in Libya, was able to phone and even to meet Abdallah in prison. Saunders writes that ‘Abdalraouf Abdallah had an important role in radicalising [Abedi]’.

Saunders has revealed many other troubling aspects to the grim tale of Salman Abedi. In 2012, after the Abedi brothers returned from Libya without their parents, Salman enrolled at Manchester College. In September, when Salman and his circle were involved in disrespectful behaviour towards female students, his older brother, Ismail, was called in to see staff in place of his parents. Nothing happened. Then, in a separate incident in October 2012, the then 17-year-old Salman assaulted a female student. The police were called, but did not press charges. In his recommendations, Saunders writes: ‘This kind of behaviour is consistent with the development of a violent extremist mindset, but is not necessarily an indication of it by any means.’

Given what we know about the Abedis’ Islamism and pre-existing antipathy towards Western liberalism, this is a remarkably mild conclusion for Saunders to draw. The Abedi brothers went on to target a concert largely attended by teenage girls, nearly all of whom were likely to be non-Muslims. The sort of behaviour exhibited by Salman while he was at college was a clear red flag.

In his report, Saunders is unusually open in his criticism of MI5. He states that ‘there was a realistic possibility that actionable intelligence could have been obtained which might have led to actions preventing the attack’. That speaks volumes. It is high time we debated more openly the failures of MI5 and other intelligence agencies when it comes to Islamic extremism.

While we’re at it, we ought to look at ourselves, too. As events in Wakefield last month have again reminded us, we prefer to look away when Islamist intolerance and violence raises its head. The time for embarrassed silence is over.

The Manchester bombing poses deeply uncomfortable questions for our society. Some of the responses to the tragedy show contemporary Britain at its most gullible. British Muslims have been fighting, dying and killing for jihadist causes at home and abroad since at least the early 1990s. Salman Abedi himself repeatedly fought for Islamist groups in Libya, in 2011 and later in 2014. Yet too many in the media and politics have responded to the threat of Islamist violence either by ignoring it or by focusing on the far lesser threat posed by the far right.

Indeed, the day after the inquiry report was published, the BBC filed a major article on its website entitled ‘I was radicalised by the far right aged 15’. The story of ‘John’, radicalised by far-right forums after the Manchester Arena bombing, was the lead item on both the BBC’s coverage of the Arena inquiry and on the BBC Manchester website.

This is a classic example of the ‘pivot response’ to terrorism, shared by far too many commentators and organisations. They will briefly acknowledge or recognise jihadist violence (although sometimes they don’t even do that), only to then pivot on to what they really feel comfortable talking about – racism, ‘Islamophobia’ and the far right.

We need to call this cowardly nonsense out wherever we find it. When we fail to do so, we lose sight of where the biggest terror threat lies – and we make it far too easy for murderous Islamists, like the Abedi brothers, to operate unseen.

Paul Stott is head of security and extremism at Policy Exchange. Follow him on Twitter: @MrPaulStott

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.