Why the culture of fear will outlive Covid

Western society was paralysed by anxiety long before the virus.

It looks as though we may no longer have to fear Covid-19. Yet a greater task awaits. To paraphrase the words of a great American president, the fight now is against fear itself.

An article from the Daily Mirror on Wednesday illustrates the state we’re in. ‘Map shows UK areas that may be ruined if Russia launched nuclear bomb on London’, reads the headline, accompanied by a graphic of the UK capital surrounded by concentric circles showing how an atomic attack might destroy the southeast of England.

Widely disseminated, it was also widely ridiculed for its sensationalist catastrophism. But its existence bears testament to the degree that fear has become the default setting in society. So what if the virus is receding, if what it leaves behind is a world frightened witless not just by the virus itself, but also by governments and the media? They have impressed an oppressive sense of anxiety on society.

This is why we should not seek to return to ‘normal’. The ‘old normal’ was part of the problem. The Covid-19 virus arrived in a world already beset with fear and anxiety, a trend identified at the end of the last century by Frank Furedi in his 1997 book, Culture of Fear. Furedi described how despite living safer and longer lives, ever more liberated from disease and suffering, we had become increasingly fearful.

The supposed dangers posed by mobile-phone masts, genetically modified foods, paedophiles – these were the staple stories of the 1990s. They were but epiphenomena. Stories of environmental disaster and terrorism were also commonplace, but they survived the new millennium.

This climate of fear has since spawned fresh symptoms. Witness our contemporary moral panics: in the past 20 years we’ve been told that the spectre of racism lurks everywhere – invisible and unwitting. In the past 10 years sexism has also assumed a demonic, ubiquitous and unseen form. Even the arguments against Brexit were framed in catastrophic, fearmongering terms.

The spectre of ‘health and safety’ became a bit of a joke in the 1990s. But we stopped laughing two years ago, when our obsession with safety at all costs – often manifest in the precautionary principle in science and overbearing risk analysis in the workplace – resulted in crippling lockdowns. Such measures happened because we allowed them to. We were terrified already, mentally inhabiting worst-case scenarios.

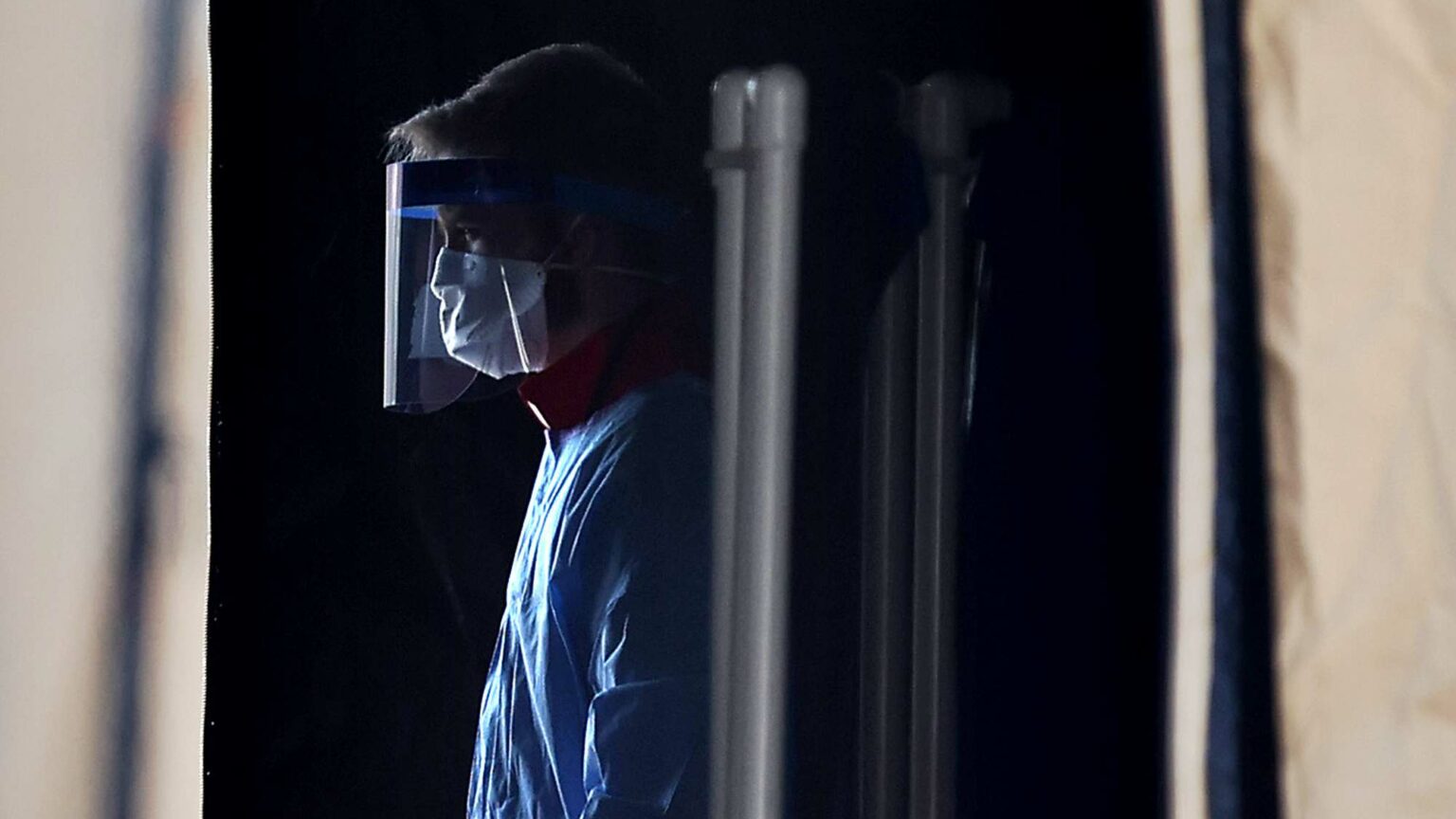

Covid-19 spread in a culture that was already ill. And it lingers in a culture that still is. Many scientists still make worst-case scenarios as if on autopilot, recalling historical scenarios when viruses became more deadly, not more mild. Many people still needlessly wear masks in the open air. Many still want restrictions to be kept in force.

The ‘culture of fear’ of the 1990s was a kind of affluenza or Yuppie flu – a neurotic phantom illness for the comfortable and well-off who no longer had any real illnesses to worry about and had too much time on their hands. So no wonder it’s the affluent, coddled ‘pyjama class’ today who also shout loudest for restrictions to stay in place.

The culture of fear has profound causes, such as the loss of authority of Western knowledge, which came under the onslaught of postmodernism and relativism in the 1990s. This has since evolved into wokery, cynical subjectivism, mistrust and even hatred of Western civilisation itself. We are mentally and intellectually rudderless in many ways.

Yet at the same time, fear culture has also been encouraged by a vast expansion in the availability of knowledge, information and misinformation, which began in the 1990s and has vastly accelerated in the past two decades thanks to technology – particularly social media. It is often said that medical students become awful hypochondriacs during their first years of study, in which they become aware of every possible malady that could kill them. We are collectively at a similar stage. We know too much. And too much information begets too much speculation.

There are some means of remedy. Read less, but read judiciously and deeply, instead of reading haphazardly and widely. Stop catastrophising and defaulting to fear – and stop deferring to those who spread it. And we should treat worst-case scenarios as last-case scenarios.

The Census should record facts, not feelings

Trans people in Scotland will be free to identify as they please on the Census, it has been reported. Last week, Lord Sandison, in the Court of Session in Edinburgh, ruled that transgender people will be able to record their sex differently on the Census to what is printed on their birth certificate. Scots will not even need a gender-recognition certificate to do so.

The foremost role of the Census is to record facts, not feelings or subjective interpretations of the world. People shouldn’t be able to literally rewrite history. People are born male or female, and are not assigned either. You can’t change this fact, even by retrospective mental gymnastics (and I pity future historians of Scotland).

This move seeks both to change history and reality itself. It presumes we can change both at the mere behest of our whims. You’d think we had become gods.

Liberal authoritarianism

Last November, when Austria announced that it was to introduce mandatory vaccines, most media outlets mentioned that those protesting against this included members of the Freedom Party. The insinuation, or at least the conclusion many readers inferred, was that those opposed to compulsory vaccinations were fascists. Few seemed to notice the irony that now, in Austria of all places, the leading so-called far-right party had become one of a rainbow multitude of anti-authoritarian and even libertarian voices.

The same irony bypass has afflicted many so-called liberal minds as events have unfolded in Canada and New Zealand, where those protesting against government and state overreach have been smeared, directly or by association, as ‘far right’ or ‘fascists’.

I say ‘so-called’ liberals deliberately. Because while today’s ‘fascists’ in New Zealand and Canada are mostly calling for less state interference, today’s ‘liberals’ are calling for more – and when in positions of power, they have imposed more. In Canada, assets have been seized from peaceful protesters thanks to prime minister Justin Trudeau’s use of draconian emergency measures last week.

The government of Jacinda Arden, who exhorts New Zealanders to ‘Be Kind’, is now held in infamy for turning her country into a kind of forbidden hermit kingdom. Images of mounted policemen from that nice country Canada wading into protestors have gone global, another warning of the politics of niceness.

Altogether a strange inversion has taken place. The so-called fascists have become libertarians, and the ‘liberals’ are now the authoritarians.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, is published by Societas.

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.