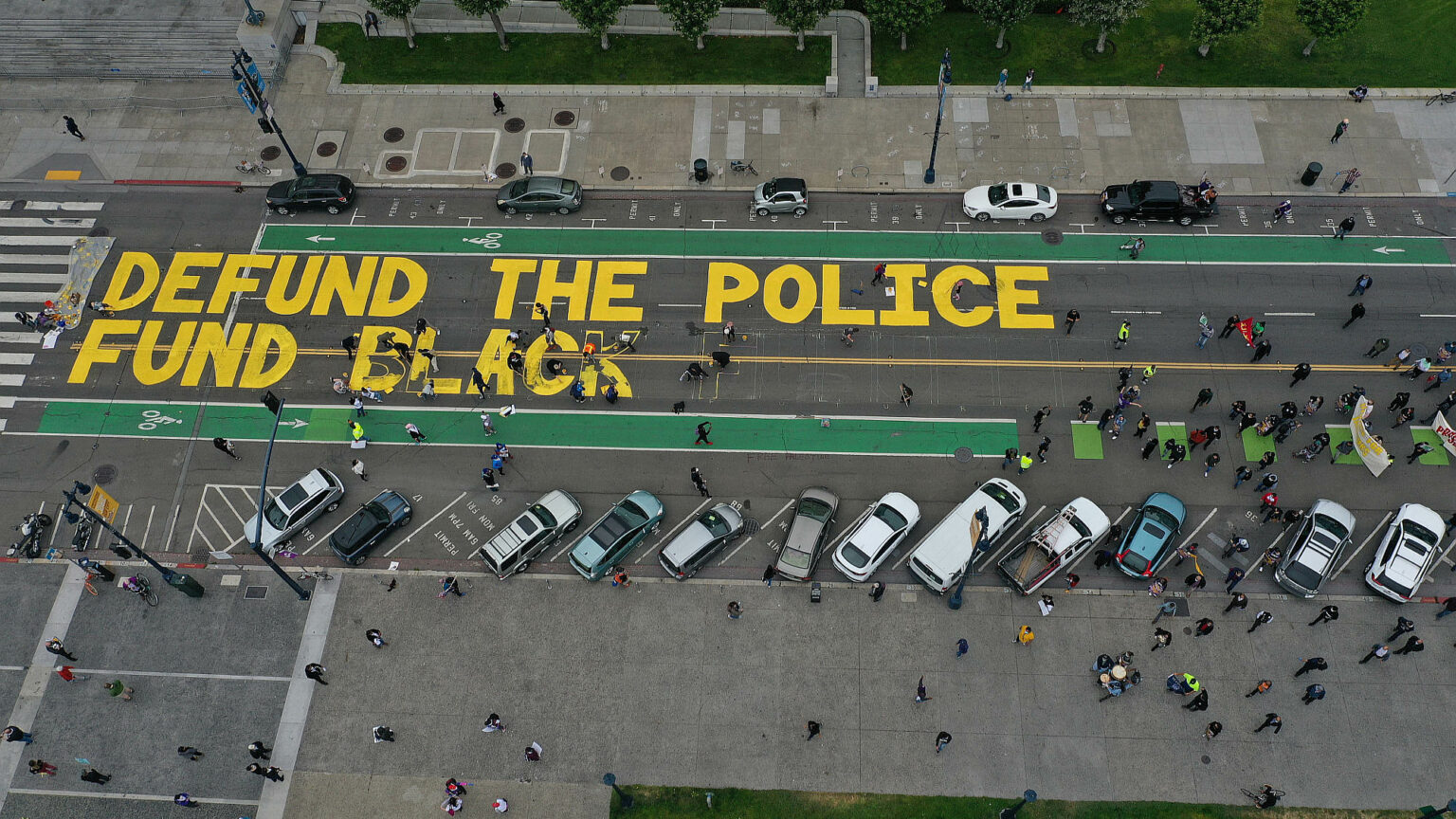

The deadly consequences of Defund the Police

How a woke slogan caused mayhem in America’s working-class communities.

Remember ‘Defund the Police’? It was the slogan du jour of the Black Lives Matter movement. It was being hollered on every street during the protests over the killing of George Floyd by Minnesota cop Derek Chauvin. In those riotous days in the summer of 2020, everyone seemed to be waving a placard or wearing a t-shirt demanding defunding. The entire in-crowd posted those three words on their social-media accounts. Even here in the UK, where cops aren’t armed and where the police-funding model is very different to America’s, the right-on lined up behind the vague, strange call for police forces to be starved of funds. A headline in the impeccably middle-class Guardian declared: ‘The answer to police violence is not “reform”. It’s defunding.’

Yet now, ‘Defund the Police’ seems to be a fast fading idea. You don’t hear it very much anymore. It might linger among the white antifa oafs who stomp around in cities like Portland and among well-to-do radical students on quiet, handsome campuses in the UK where there’s very rarely any need to call the cops. But on the streets, in politics, in the press, ‘Defund’ seems to have fizzled out. The old woke roar is barely a whimper now. And it isn’t hard to see why. This slogan has proven lethal. It has been an unmitigated disaster in numerous US cities. The cutting of cops’ budgets did not give rise to the new dawn of flowery peace and racial justice that the virtue-signalling defunders fantasised it would. On the contrary, it helped to stoke violent crime, further destabilise city life, and make life even harder for poor black and brown communities in particular. The lesson here is clear: wokeness kills.

The idea of ‘Defund the Police’ has been around for a couple of decades. But it exploded into public view following the killing of Floyd in May 2020. It’s a simple-sounding proposition: you take public money away from police departments that are too often heavy-handed and racially prejudiced and plough it instead into fairer non-policing forms of ‘public safety’, like mental healthcare, youth services, improvements to housing, and so on. And hey presto, there’ll be fewer trigger-happy cops on the streets and more happy citizens no longer tussling with mental problems and crappy living conditions. The reality, of course, as could have been predicted by anyone who doesn’t live in a gated community and get all their news from the New York Times, has been rather different.

‘This US city was working to cut its police budget in half – then violent crime started to rise’, said a headline in the Guardian in March 2021, less than a year after that very same bastion of liberal correct-think was telling its readers that defunding cops is the ‘answer’ America is looking for. The March 2021 piece was about Oakland in California, where local officials took the post-Floyd anger of 2020 to heart and made plans to cut police spending by a whopping 50 per cent – around $150million a year. Then the killings started. And other forms of crime. In 2020 there were 107 murders in Oakland, compared with 75 in 2019. The spike in violence led five black members of Oakland’s taskforce on public safety to write a letter warning officials that ‘even more lives will be lost if police are removed without an alternative response being put in place’.

There have been similar rises in violence in other American cities that have planned or actually made cuts to police budgets. Throughout America, homicides rose by 30 per cent in 2020. And they continued rising in 2021. ‘Cities across the US are breaking all-time homicide records this year’, reported CNN in December. CNN reports that more than two-thirds of America’s most populated cities experienced more homicides in 2021 than they did even in 2020. Last year some American cities broke their all-time homicide records. Philadelphia suffered 513 homicides, smashing its previous annual high of 503 in 1990. Indianapolis had 230 homicides, breaking its previous record of 215 – which was in 2020. Things have gotten so bad that even the New York Times has been moved to ask: ‘Why are so many Americans killing one another?’

Speaking of New York, crime is surging in NYC, too. Already this year things look bad. An extraordinary 72 of the city’s 77 police precincts have experienced more crime in the first few weeks of 2022 than they did in the same period in 2021. And that’s saying something, given how strange and fraught 2021 was. So far this year there has been a 35 per cent rise in robberies, a 35 per cent rise in rapes and a 30 per cent rise in shooting incidents in NYC compared with the same period in 2021 (killings, however, are down, by 13 per cent). ‘No neighbourhood is safe’, says one Brooklyn cop. Is it a coincidence that this is happening in a city where right-on officials responded to the political tumult of 2020 by agreeing to cut police funding by a whopping $1 billion? Many NYC residents are pretty certain it isn’t. Marisol Sanchez, whose son was shot to death in the Bronx in August last year, slammed the Defund the Police movement, saying that poor communities like hers ‘just don’t see [cops] no more’.

In numerous cities, there seems to be a pretty clear relationship of causation, or at least of inflammation, between ‘defund’ policies and blow-ups in violent crime. So in Austin, Texas, officials cut $20million from the police budget. This led to the dissolution of some law-enforcement units. ‘In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests this summer [2020], we made a significant cut to policing dollars’, boasted once council member. What happened in 2021? Austin experienced its highest number of homicides in 20 years. Aggravated assault rose, too. ‘Austin police chief says city doesn’t have enough officers’, said a news headline in December. There were cuts to police funding in the city of Los Angeles, too: $89million was taken away from the LAPD and rerouted to other services. With depressing predictability, there were 397 murders in LA in 2021, the most it has experienced in 15 years.

Not surprisingly, the focus is now turning in many US cities, away from ‘defunding the police’ to, in the words of The Economist, ‘refunding the police’. ‘As violent crime leaps, liberal cities rethink cutting police budgets’, The Economist soberly reported last month. LA cops are now set for a budget boost. San Francisco’s mayor, London Breed, initially supported the idea of defunding the police – now she says she will be ‘less tolerant of all the bullshit that has destroyed our city’. That’s a remarkable turnaround. The Economist says many ‘liberal’ city officials across the US have twigged, finally, to a fairly obvious fact – that ‘if a city wants to drive down its murder rate, hiring more officers seems a reasonable place to start’.

But even as defunding turns to refunding, and even as woke politicos start to recognise that cops can be useful in crime-ridden communities, the question remains – how was this ‘bullshit’ allowed to ‘destroy cities’? Why did so many accept and promote the preposterous idea that cutting police resources and having fewer officers on the streets would help to make communities – especially black communities – safer? Many people warned against the slashing of police budgets, and yet still it happened. In NYC, for example, in August 2020 – right around the time of the BLM and Defund uprisings – influential people of colour were sounding the alarm about defunding the police. City councilwoman Vanessa L Gibson, a representative for the Bronx, said her constituents ‘want to see cops in the community’. Numerous black New York officials counselled against Defund. One described this woke belief in trimming cop numbers as a form of political ‘colonisation’ pushed by white progressives. Another said it had the whiff of ‘political gentrification’.

Polls over the past year have shown that many working-class Americans are deeply uncomfortable with the idea of defunding the police. Some surveys show that black Americans oppose Defund more than white Americans do. In Minneapolis, for example, where George Floyd was killed, three quarters of black respondents to a poll about policing said the city should not reduce its police force. Black respondents were ‘considerably more opposed [to Defund the Police]’ than white respondents were. In a similar survey in Detroit, a majority of white respondents said ‘police reform’ was the major issue facing their city, whereas a majority of black respondents said ‘public safety’ was their main concern. For them, police reform was the lowest priority. As Slate says, this seemingly incongruous racial disparity can be seen in various parts of the US, where ‘many white people are open to police reform, and many black people are wary of curtailing law enforcement’. A Pew Research survey found that growing numbers of black Americans now want police funding to be increased. Strikingly, black and Hispanic Democrats are more likely than white Democrats to want more spending on cops. Thirty-two per cent of white Democrats want increased police funding, compared with 38 per cent of black Democrats and 39 per cent of Hispanic Democrats.

So, given the warnings from political representatives – who were in many cases representatives of the very communities that white liberals claim they want to protect from cops – and given all the survey findings showing that the American people ‘want more spending on police in their area’, how on earth did the Defund the Police idea take off? How did it make its way even into sections of the Democratic Party and into council chambers and high-up political decision-making? How did it come to be swooned over by every supposedly respectable observer from the Guardian to the NYT to, of course, the Twitterati and Instagram influencers?

It’s because the new elites, these noisy purveyors of ‘woke’ thinking who have come to dominate the political and media classes, are now phenomenally removed from ordinary people and from the needs and interests of working communities. To such an extent that they couldn’t even see that there might be a problem with withdrawing police from poor, isolated, atomised communities in which crime and anti-social behaviour are significant problems. The story of Defund, the spectacular collapse of this toxic woke slogan, the hardship this eccentric ideology has caused in many communities, is really a story of the unbridgeable chasm that now separates the decadent new establishment from the reasoned public that wants to enjoy a safe, good, fruitful life.

To be sure, the recent surge in crime in the US is a complex phenomenon. There are many contributing factors. Defund was one – with its physical reduction of police resources and, in some cases, actual law-enforcement units – but there were others, too. As an interesting analysis in the New York Times says, we are not living in normal times. The Covid pandemic, for example, was a ‘mass death event that ruptured the fabric of American life’. Schools and other community institutions ‘evaporated’, meaning many young people were no longer as focused and disciplined as they once were. The space for problematic behaviour grew.

There is also the problem of ‘general anomie’, says the Times. That is, the ‘unravelling of the social contract’ that we have witnessed in recent years, which could very well reduce ‘pro-social and relational’ behaviour and create the conditions for more anti-social and even criminal forms of behaviour instead. (Perhaps the NYT will now pay more attention to those of us who think genuinely progressive politics means challenging anomie through solidarity, strong communities and gainful employment, and ditch its addiction to the hyper-atomising cult of identity politics.) Yet as even the NYT must admit, in addition to this mix of virus and anomie – and very possibly exacerbating this mix – there is the problem of ‘changes in police behaviour’. ‘Protests against police brutality [make] officers more afraid or unwilling to do their jobs’, says the NYT in its analytical explanation for why ‘so many Americans are killing one another’, which is about as close as this newspaper, which was so sympathetic to the BLM mayhem, will get to admitting that the ferocious and often fact-lite demonisation of American cops over the past two years may have had negative consequences for many communities, especially poorer ones.

So, two things seem to be happening here. First, there’s the rupturing of social bonds, a much-discussed phenomenon these past few decades, which could be inflaming community breakdown and crime. And second, there is the far more conscious, politically motivated decision to withdraw or at least problematise certain forms of police activity, which will have given a green light to criminal opportunists and created more arenas for violent behaviour. This latter phenomenon is a product of one of the most curious political events of our times: the upper middle classes’ turn against law and order; the elites’ growing agitation with the idea of maintaining social order and with all the tools that are necessary to such an endeavour – policing, force, judgement and control.

It is remarkable how much more pronounced anti-police sentiment is among middle-class graduates and the professional elites than it is in many working-class communities. As the African-American mayor of Newark Ras Baraka said in the summer of 2020, Defund was a ‘bourgeois liberal’ ideology, pushed by out-of-touch members of the observing class. The African-American former mayor of Philadelphia, Michael Nutter, was even more cutting. There is an ‘audacity of ignorance and white privilege’ in those who support anti-police policies and who refuse to acknowledge the spike in crime that these policies can cause, he says. In response to Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s liberal, police-critical DA, who has denied that Philadelphia is experiencing a crisis of crime, Nutter says: ‘It all goes back to supremacy, paternalism. “I’m woke. I’m paying attention. I spend a lot of time with black people. Some of my best friends…” All that bullshit.’ Defunding the police is very often a case of privileged white liberals positioning themselves as the saviours of black communities, says Nutter, while in reality causing more disarray in those communities.

The upper middle-class turn against law and order can be seen in the UK, too. As in the US, anti-police sentiment, as a political position, seems stronger among graduate leftists and the commentariat than it is in working-class communities that want more bobbies on the beat. Indeed, the slogan ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards) has gone from being the cry of working-class football fans four or five decades ago to being the intellectual property of university-educated middle-class radicals. The signalling of anti-police virtue seems to be a higher priority for the British cultural elite than tackling crime. Witness their unwillingness seriously to grapple with problems like knife crime, urban violence and Islamist extremism. They would rather let those problems carry on blighting mostly poor and ethnic-minority communities than acknowledge there is a role for the authorities in tackling such crime and protecting the integrity of community life. Just as in the US, anti-police posturing in the UK is now a largely ‘bourgeois liberal’ ideology.

It is essential to note that this elite turn against law and order is not motored by a belief in freedom or by trust in ordinary people’s ability to govern their communities for themselves. Indeed, a great contradiction of our time is that the woke elites continually signal their disdain for ‘authoritarian’ policing while expressly supporting new, even more insidious forms of policing – of speech, of thought, of personal behaviour. They disdain traditional applications of law and order, while demanding more intimate forms of control in the shape of cancel culture and nanny statism. They bristle at supposedly old-fashioned ideas about maintaining social order while seeking to enforce cultural order – that is, intellectual order and lifestyle order. That’s because the driver of the bourgeois embrace of the Defund ideology is not trust in liberty and community, but rather the upper middle-classes’ growing alienation from the values that underpin traditional forms of policing in the community.

It is not surprising that elites who see racism everywhere, who have convinced themselves that crime is a natural byproduct of poverty rather than something people also choose to do, who believe that less well-off people cannot be held entirely responsible for their actions, and who have adopted a paternalistic attitude towards black and ethnic-minority communities in particular, are turning against traditional ideas of policing and order. And it is not surprising that their hyper-relativistic, pseudo-radical policies have caused so much harm. Working-class victims of crime, ethnic-minority communities struggling with rising violence – this is the debris of the woke derangement, the collateral damage of a cultural elite’s fashionable abandonment of the belief that it is good and important to tackle crime. Wokeness isn’t only annoying – it’s dangerous.

Brendan O’Neill is spiked’s chief political writer and host of the spiked podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show. Subscribe to the podcast here. And find Brendan on Instagram: @burntoakboy

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.