Why Manchester was right to resist more restrictions

There’s little evidence that closing pubs will stop the spread – or that hospitals will be overwhelmed.

After 11 days of negotiations between local leaders and central government, Boris Johnson yesterday decided to impose ‘Tier 3’ restrictions on Greater Manchester. Households will no longer be able to mix indoors at all or outdoors in hospitality venues or private gardens. Hospitality venues can only remain open if serving a ‘substantial meal’. And travel in and out of the area is now advised against.

With a queue of other areas now under threat of the same restrictions, it seems that significant chunks of northern England will be in ‘lockdown lite’ very soon, hammering livelihoods and making everyday life miserable. Greater Manchester’s opposition has opened up the possibility of reversing the tide flowing towards ever-greater restrictions, especially since the evidence that placing restrictions on hospitality venues like pubs and restaurants can significantly reduce infection rates isn’t very strong.

It’s true that the UK’s ‘R’ number – a measure of the spread of the virus – went above 1, indicating rising infection numbers, a few weeks after pubs and restaurants reopened. The Scottish government also claimed, in defending its restrictions earlier this month, that 26 per cent of people who tested positive mentioned ‘exposure’ to pubs and restaurants. Certainly, lots of people go out to pubs and restaurants, but that doesn’t mean they got infected there.

According to the UK government’s most recent weekly Covid-19 surveillance report, over the four weeks leading up to 27 September, there had been 2,529 acute respiratory-infection incidents. Of these, 127 were associated with food outlets and restaurant settings – just five per cent. However, these were incidents where multiple people were affected, so they don’t capture the exact number of cases.

In other words, there is no decisive piece of data to make the case either way. In truth, governments have concluded that if they want to keep schools, universities, shops and other workplaces open, clamping down on hospitality venues is the one thing they can do to restrict infection rates.

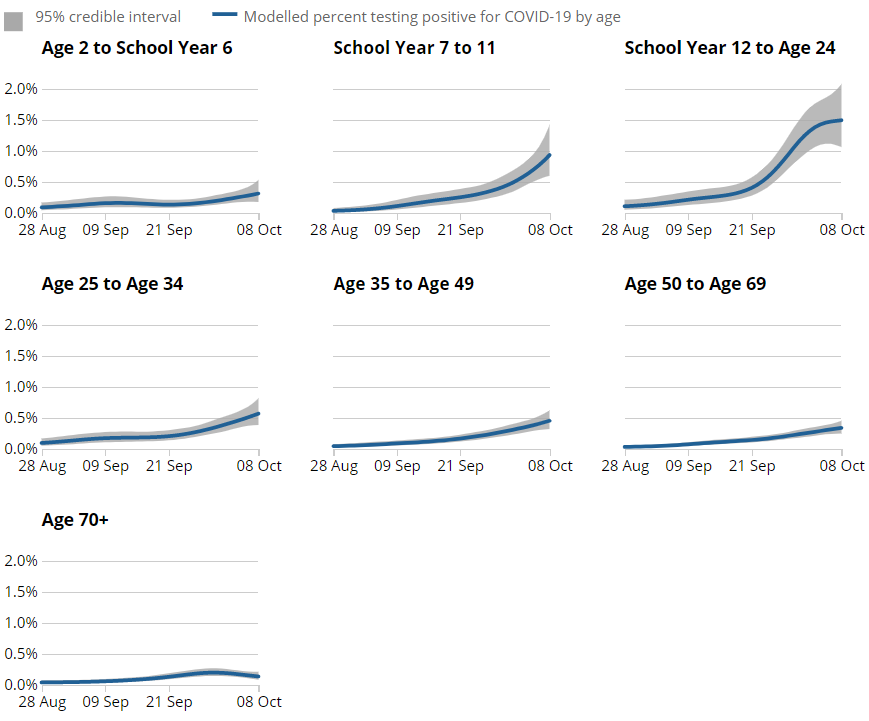

But the recent rise in cases is clearly associated with a specific age group: young people. According to the ONS Infection Survey Pilot, which tests and re-tests a representative sample of the UK population, positive tests are overwhelmingly in 18- to 24-year-olds. For the most recent date available, 8 October, the central estimates for cases were 1.49 per cent among school year 12 to age 24 compared to 0.13 per cent among the most vulnerable over-70s. A major driver for this would have been students congregating together at the start of the university term. In a predictable development, infection rates in this age group seemed to have plateaued.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t growth across the UK. It’s entirely predictable that cases of seasonal illnesses like Covid-19 and influenza will rise during autumn and winter. It’s also predictable that hospitals will come under a lot of pressure in the next few months and would prefer not to have to deal with this new disease on top of the usual winter pressures. But the rapid rise of recent weeks has been among younger people who generally do not get a serious illness from Covid-19 and that rise is tailing off.

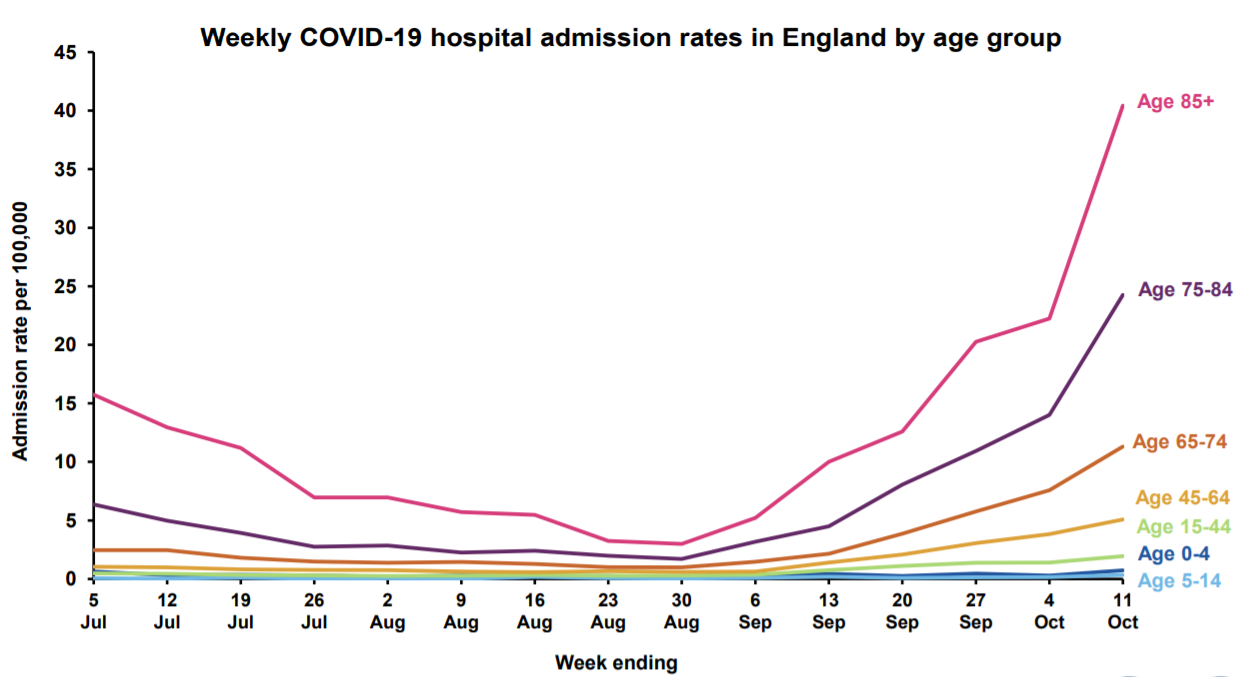

In yesterday’s press conference, the deputy chief medical officer for England, Professor Jonathan Van-Tam, claimed again that cases taking off in younger people would eventually spread into older age groups and showed some ‘heat maps’ to demonstrate the point. However, he also showed another chart which appeared to show something different: that Covid-19 hospitalisations for all age groups took off at the start of September. Could seasonal factors and age be more important than simple contagion?

Another strand of the government’s case is that further measures were required because hospitals around Greater Manchester are under serious threat of being overwhelmed by cases. Oddly, the Guardian seems to have played a part in helping the government by promoting this argument. Earlier this week, an article claimed that ‘by last Friday the resurgence of the disease had left the ICUs of hospitals in Salford, Stockport and Bolton at maximum capacity, with no spare beds to help with the growing influx’.

Firstly, intensive-care beds are always busy at this time of year and Manchester’s occupancy rates seem to be in line with previous years. Secondly, capacity is not fixed. Other nearby hospitals can take up the slack and more beds can be opened up if required. At worst, it may mean non-urgent operations have to be postponed. This is unfortunate but not uncommon. The NHS is resilient. And supplies of PPE, ventilators and much more are far better than when the crisis first began in March. There are also the barely used Nightingale hospitals on standby.

It seems that governments across the UK have tunnel vision when it comes to Covid-19. The only response to rising cases is more restrictions and efforts to reduce case numbers – at the expense of the economy and basic freedoms – rather than prioritising help for the most vulnerable.

The leader of Manchester City Council, Sir Richard Leese, has taken a different view to the government. He has proposed the creation of a £14million fund to help shield those groups at highest risk of serious illness. He said: ‘Most people who test positive for the virus are not getting particularly ill. They are not the problem. If this is the evidence, wouldn’t it be much better to have an effective shielding programme for those most at risk, rather than have a blanket business-closure policy of dubious efficacy?’

Instead, millions of people will be unable to meet friends and family, businesses will close – many permanently – for doubtful gains. The only silver lining is that Manchester’s resistance to these restrictions may embolden other local authorities to push back against them.

Rob Lyons is convenor of the Academy of Ideas Economy Forum.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.