Long-read

The shameful story of Britain’s backdoor blasphemy laws

Liberal cowardice has fuelled Islamic intolerance – and cost lives.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Asad Shah. The name doesn’t mean much to people in Britain today. But it really should. Shah was a Glasgow shopkeeper, beloved by his Shawlands community. The 40-year-old was also a bit of an amateur YouTuber. He uploaded hundreds of videos, forever perched behind his shop counter, in which he preached peace, love and unity. In one clip, he can be seen helping a six-year-old cut a birthday cake, along with the boy’s mother. Shah had known the boy, and his mother, since he was a baby. Even after the family moved away, celebrating the boy’s birthday in Shah’s shop was still an annual tradition. Shah was also an Ahmadi, belonging to a small Muslim sect deemed to be heretical by many Muslims, because Ahmadis believe that Muhammad isn’t the final prophet. Shah, in some of his videos, even suggested that he himself was a prophet. For making and publishing those videos, Asad Shah lost his life. In the most barbaric fashion imaginable.

At 9pm, on 24 March 2016, Tanveer Ahmed entered Shah’s newsagents carrying a knife. The 31-year-old cab driver had travelled to Glasgow from his home in Bradford, incensed by Shah’s claims to holiness. Ahmed had left a friend a voicemail, saying: ‘Listen to this guy, something needs to be done, it needs to be nipped in the bud.’ He attacked Shah, stabbing him repeatedly in the head and upper body. Shah tried to escape outside. Ahmed followed. He repeatedly stamped on Shah’s head, shattering almost every bone in his face. As his victim lay bloodied and still, Ahmed walked into a bus shelter and waited for police to arrive. He told the cops, as they moved to apprehend him: ‘I have nothing against you and so I am not going to hurt you. I have broken the law and appreciate how you are treating me.’ But Ahmed remains unrepentant about his crime. During his trial, he put out a statement: ‘This all happened for one reason… Asad Shah disrespected the messenger of Islam, the prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him.’ Ahmed is now six years into a life sentence.

I thought about Shah in recent weeks, as the goings on in Wakefield began to emerge. Four boys have been suspended from Kettlethorpe High School for bringing a Koran into school and accidentally dropping it on the floor. Rumours originally swirled, thanks in part to a local Labour councillor, that the holy book had been desecrated. The autistic boy who brought it into school – on a dare, as it transpired – was menaced with death threats. His home was threatened with arson. And yet the response of the authorities, in effect, was to throw these boys under the bus. Not only did the school suspend these kids – for lightly scuffing a book – it also called the police in. The scuffing has been recorded by police as a ‘non-crime hate incident’, potentially haunting those boys’ job prospects for years to come. The mother of the autistic boy later addressed a local mosque, flanked by the school’s headteacher and a senior policeman, saying she would not pursue charges on the death threats so long as her son wasn’t harmed.

The mosque’s imam, Hafiz Muhammad Mateen Anwar, told the crowd that night that anyone who resorted to threats or violence ‘is not truly following the teaching of Islam’. Still, Anwar stressed, ‘we will never tolerate the disrespect of the holy Koran. We will sacrifice our lives for it.’ He said all this sat next to a police officer, inspector Andy Thornton, who also spoke. Thornton could be seen nodding sagely as Anwar said the Koran incident was not being ‘brushed under the carpet’. This meeting, seemingly held to tamp down tensions, only underlined the shameful reality: that in modern-day Britain, disrespecting Islam, even accidentally, is a risky business. Even if you’re a schoolboy. And in trying to assuage these ‘religious sensitivities’, the school and the police had unwittingly helped place a target on that child’s back; punishing him, and his friends, while letting those threatening to kill him off the hook.

Did we learn nothing from Asad Shah? Did we learn nothing from Batley Grammar – another Yorkshire school, host to another blasphemy scandal, just 10 miles from Kettlethorpe, only two years ago? There, a teacher was forced into hiding after he showed Muhammad cartoons as part of a religious-studies class about free speech. Hardline religious protesters showed up outside the school, shutting it down for days. A local Islamic charity, Purpose of Life, published the teacher’s name online. The school gave in then, too. Batley Grammar’s headteacher, Gary Kibble, issued an ‘unequivocal apology’ to the mob gathered at his school’s gates. Today, that teacher is still in hiding with his family, their names and phone numbers changed. People’s lives are being torn apart, upended, occasionally ripped away from them entirely, all because they have ‘blasphemed’ against a religion. This shameful, medieval situation reflects so much that has gone rotten with modern Britain.

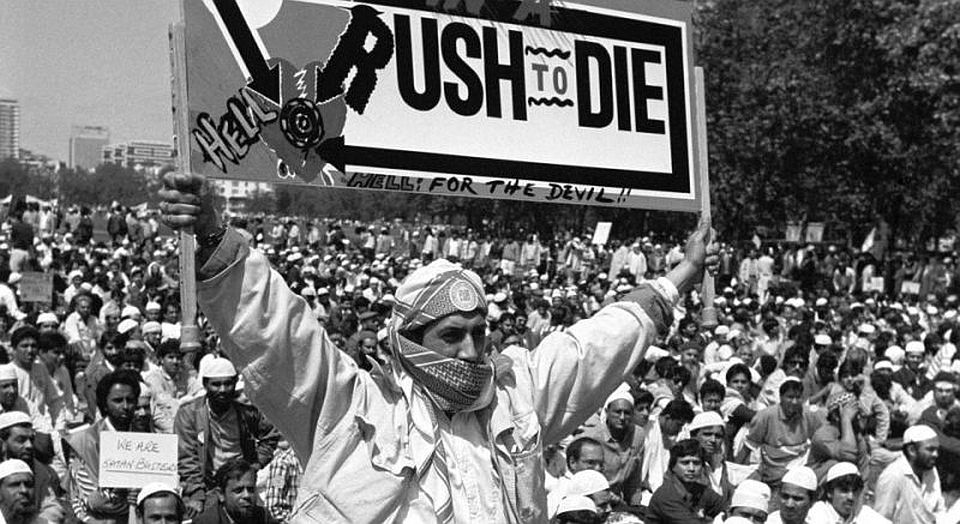

Over the past 30 years or more, Britain has been nurturing this Islamist-style intolerance in our midst. It goes back to the Salman Rushdie affair, and to how the fatwa – the price placed on the author’s head by the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989; a bounty that a knifeman in New York came terrifyingly close to claiming last year – first came about. The first protest against The Satanic Verses, the ‘blasphemous’ novel charged with insulting the prophet, was not on the subcontinent or the Middle East, but in Bolton on 2 December 1988. Another protest, in Bradford in January 1989, made international headlines. These were the culmination of a homegrown, anti-Rushdie campaign – albeit one, as Tim Black has noted on spiked, that was fomented by an array of largely Saudi-backed Islamist groups. These protests were also kindled by a policy of state multiculturalism, which primed British Muslims to see themselves as separate, distinct, with their own state-funded ‘community groups’ acting as their ‘authentic’ voice.

When the ayatollah issued his fatwa, on Valentine’s Day 1989, changing the world forever, he did so with the all-but-direct encouragement of British Muslim activists. Kalim Siddiqui, then director of Britain’s Muslim Institute, reportedly met with Iran’s foreign minister in the VIP lounge of a Tehran airport the day the fatwa was announced, urging action on Rushdie. Until his death in 1996, Siddiqui took ‘great pride’ in his part in bringing about the fatwa, which has now claimed the lives of dozens of people and disfigured Rushdie for life. (As a result of the attack on 12 August 2022, when Rushdie was stabbed on stage at a literary festival by 24-year-old Hadi Matar, Rushdie has lost sight in one eye and one of his arms is now partially disabled.) The UK anti-Rushdie movement culminated in a 20,000-strong rally in Hyde Park in May 1989. Rushdie effigies were burned, placards openly called for his murder, and protesters turned in a petition to Downing Street, demanding that Britain’s by-then-defunct blasphemy laws be extended to protect Islam. Among the most zealous anti-Rushdie activists were born-and-bred, first-generation Brits. As an account from a similar 1990 rally noted: ‘The most murderous placards were being carried by these non-observant [young men].’

The response from much of the British establishment was shameful. Margaret Thatcher’s government might have begrudgingly offered Rushdie police protection, but her ministers took every opportunity to denounce him, seemingly because they were offended by Rushdie’s commentary, as a British Indian, on racism in British society. Norman Tebbit dubbed him an ‘outstanding villain’ whose ‘public life has been a record of despicable acts of betrayal of his upbringing, religion, adopted home and nationality’. Labour MPs with large Muslim constituencies tried to exploit the controversy for political gain. Keith Vaz MP, a Catholic of Goan origin, led a march of thousands of Muslims in Leicester, calling for The Satanic Verses to be banned. He called the march ‘one of the great days in the history of Islam and Great Britain’. Rushdie later claimed that Vaz had phoned him a few weeks prior, offering his ‘full support’ and describing the fatwa as ‘absolutely appalling’.

The fatwa also brought out an emerging fissure on the left, as socialist writer Matt Cooper has noted. At first, many left-wingers came out in support of Rushdie. In April 1989, in response to calls for the blasphemy laws to be extended to Islam, Tony Benn MP introduced a backbench bill, calling for them to be abolished entirely. He had the backing of many left Labourites. But there were some notable exceptions. Tottenham MP Bernie Grant and Bradford West MP Max Madden essentially sided with the protesters. Over time, the Socialist Workers Party went from defending Rushdie – conducting a sympathetic interview with him just before he went into hiding – to making excuses for his tormentors and accusing pro-Rushdie liberals of ‘Islamophobia’. The SWP, Cooper argues, came to believe that an emerging Muslim identity politics could be channelled into broader struggles – the early stirrings of a perverse alliance between sections of the radical left and ‘reactionary religious ideology’.

The story of the fatwa, then, is not one of Eastern intolerance wreaking havoc upon an unsuspecting West. The anti-Rushdie movement took firm hold within the United Kingdom, among British Muslims who had all been essentially encouraged by state multiculturalism to see themselves as separate and distinct, both from the white British majority and other minority groups. The anti-Rushdie protesters were, in so many ways, pushing at an open door. The fury and intolerance of the book-burners was met with the cowardice and opportunism of the political class, the cultural elites and sections of the left. The anti-Rushdie movement would then become institutionalised, its leaders setting up Muslim organisations and therefore lent the phoney legitimacy of ‘community leaders’. Iqbal Sacranie, a key anti-Rushdie activist, went on to found the Muslim Council of Britain; this man, who memorably said ‘death, perhaps, is a bit too easy’ for Salman Rushdie, was knighted by the Queen in 2005.

The anti-Rushdie movement did not succeed in extending England’s blasphemy laws to Islam. Those laws, long since a dead letter, were repealed in 2008. But this movement absolutely succeeded in establishing Islamic blasphemy law by the backdoor, enforced not by clerics and edicts, but by mob intimidation and institutional cowardice. Examples of this are now 10-a-penny. In 2008, Random House dropped The Jewel of Medina, a novel which told the story of Muhammad’s relationship with his 14-year-old wife Aisha, because it ‘might be offensive to some in the Muslim community’. (Jones found another UK publisher, Martin Rynja. His Islington home was firebombed a few days before the book’s publication.) Maryam Namazie, an Iranian-born leftist and anti-Sharia campaigner, was No Platformed at Warwick University in 2015, after the students’ union deemed her ‘highly inflammatory’. Last year, groups of Sunni Muslim protesters managed to get The Lady of Heaven, a Shia-made film, pulled from cinemas nationwide, because it portrayed a ‘blasphemous’ version of Islamic history.

Who needs a blasphemy law, when you’ve got mob censorship? Still, the legal threat to the right to blaspheme against Islam – or any faith or worldview – hasn’t exactly gone away, either. In 2006, the New Labour government passed its Racial and Religious Hatred Act, making it an offence to incite hatred against a person on the grounds of their religion. The Blairites were effectively replacing the old blasphemies, relating to the established church and religion, with new ones around nebulous forms of ‘hate’. If it wasn’t for a successful campaign to amend the legislation, led by comedian Rowan Atkinson and Rushdie, we might have ended up with a mix of the two – with prohibitions on the new blasphemies as well as the old. The original draft of the bill would have criminalised ‘abusive or insulting’ language about religion, which as campaigners pointed out would have made religious as well as anti-religious speech a potential target for state censorship.

Of course the perennial problem with censorship is that it never stays put. Restrictions on ‘hate speech’ have spread like fungus since then, the definition growing wider by the year. And, inevitably, those who would criticise or demean Islam have found themselves in legal trouble. In 2015, Pastor James McConnell, a firebrand Northern Irish preacher, was put on trial for ‘grossly offensive remarks’. His crime was to call Islam ‘Satanic’, from his own pulpit. But because the sermon was streamed online he was charged under the now-infamous Communications Act. (He was cleared after a three-day trial.) An elderly Christian street preacher in north London was arrested in 2019 for ‘breaching the peace’ – reportedly, he had made ‘Islamophobic’ comments. (He was later released without charge.) Perhaps strangest of all, in 2018 alt-right Canadian YouTuber Lauren Southern was banned from the UK for life, after she handed out leaflets in Luton proclaiming that ‘Allah is Gay’.

England’s old blasphemy laws – in the words of Lord Scarman in 1979, as the Law Lords wrestled with the case of Whitehouse v Lemon, the last successful blasphemy trial in the UK – were important to ‘safeguard the internal tranquillity of the kingdom’. (Scarman also supported extending the law to all religions.) This logic seems to underpin our new, unofficial blasphemy laws against offending against Islam. Where the old establishment felt criticising the Church risked shaking the social order, so the new establishment thinks mocking Muhammad will unleash religious intolerance and division. Both are wrong. Freedom of speech can certainly be raucous, outrageous, revolutionary. It can bring down elites and propel social change, which is why it is – or at least was – a fundamentally radical, progressive ideal. But it is also the means through which we can have out our differences as citizens without resorting to violence or threats. By capitulating, time and again, to the intolerance of Islamic religious hardliners, by refusing to hold the line on freedom of speech, we have fuelled Islamic intolerance, not dampened it.

Freedom of speech would not exist without blasphemy, without radicals and troublemakers who dared to say heretical, rude and offensive things about Gods and prophets. This is what freedom of speech is built on. To throw all of that out in an attempt to shield a religious group from offence is not caring or anti-racist. Quite the opposite. It smears all Muslim Brits as hardline and intolerant, incapable of having their views challenged, incapable of being full and equal citizens in a modern liberal democracy, relegated to the status of overgrown infants or volatile brutes who must be tiptoed around forever. ‘It is almost a racist argument’, said Salman Rushdie in the aforementioned interview with the Socialist Worker in February 1989, just before he went into hiding: ‘Because it’s based on the assumption that you take the most backward aspect of a culture and say that’s the culture. Anything that is progressive is regarded as Westernised and dismissed.’

Opposing these backdoor blasphemy laws isn’t just about defending the white Brit’s right to criticise Islam. It is also about the right of minorities – within Islam and without it – to live their lives and express their views without fear of violence or intimidation. Opposing these backdoor blasphemy laws, as we’ve learned to our shame in recent years, is also essential to us being able to offer refuge to those fleeing persecution in authoritarian Muslim countries. In 2009, Asia Bibi, a Pakistani Christian, was accused of blasphemy, savagely beaten, found guilty and sentenced to death. She spent eight years on death row in Pakistan. While she was eventually cleared of her charges, she was forced into hiding – and into seeking asylum abroad – by mobs of her countrymen baying for her blood. Her application for asylum in the UK was quietly rebuffed in 2018. The reason? Reportedly, then prime minister Theresa May was given official advice, arguing that Bibi’s presence in Britain would ‘stoke tensions’ among sections of the Muslim community.

That shameful episode brings us back to Asad Shah. There is a line that connects him and Bibi. Tanveer Ahmed, Shah’s killer, was an admirer of Mumtaz Qadri, a Pakistani Sunni who assassinated Punjab governor Salman Taseer in 2011. Qadri’s motive? Taseer had called for the pardon of Asia Bibi. Ahmed even wrote adoring letters to Qadri before he was executed in Pakistan. Another thing Shah and Bibi shared is that they both had to leave their native Pakistan to escape violent religious persecution. Shah’s family moved to Scotland in the 1990s, after his father’s pharmacy was set on fire. They had faced years of threats and intimidation on account of their Ahmadiyya Muslim faith. After Shah was killed, on the streets of supposedly liberal, secular Britain, his brother told the BBC that the Shahs were planning to up sticks once again. ‘The family don’t feel safe anymore living here in Scotland’, he said. ‘We didn’t suspect something like [this] would happen in the UK.’

Few would have. But when you look back over the past 30 years it makes a perverse kind of sense. We failed to stick up for Rusdhie. We failed to offer asylum to Bibi. We looked the other way at Batley Grammar. Now we’ve thrown an autistic boy to the wolves. We have somehow come to believe that capitulating to the intolerance of right-wing religious bigots is the road to liberal, multicultural harmony. Blame for the murder of Asad Shah lies squarely with Tanveer Ahmed. But his murderous fury is only the keenest, most unhinged expression of an Islamic intolerance that has been curdling in our midst for some time, that our cowardly elites have all but encouraged. For the sake of freedom of speech, for the sake of tolerance, for the sake of British Muslims who do not want to be treated as the stage army of a extremist fringe, and for the sake of the communities on the receiving end of this medieval fury, we need to fight for our right to blaspheme all over again.

Tom Slater is editor of spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Main picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.