Long-read

The fatwa and the birth of Muslim identity politics

The Rushdie affair transformed Islam from a private religion into a global, politicised identity.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

So, The Satanic Verses controversy is not ancient history after all. The sight of Salman Rushdie in hospital, recovering from a brutal knife attack, has surely left no one in any doubt of that.

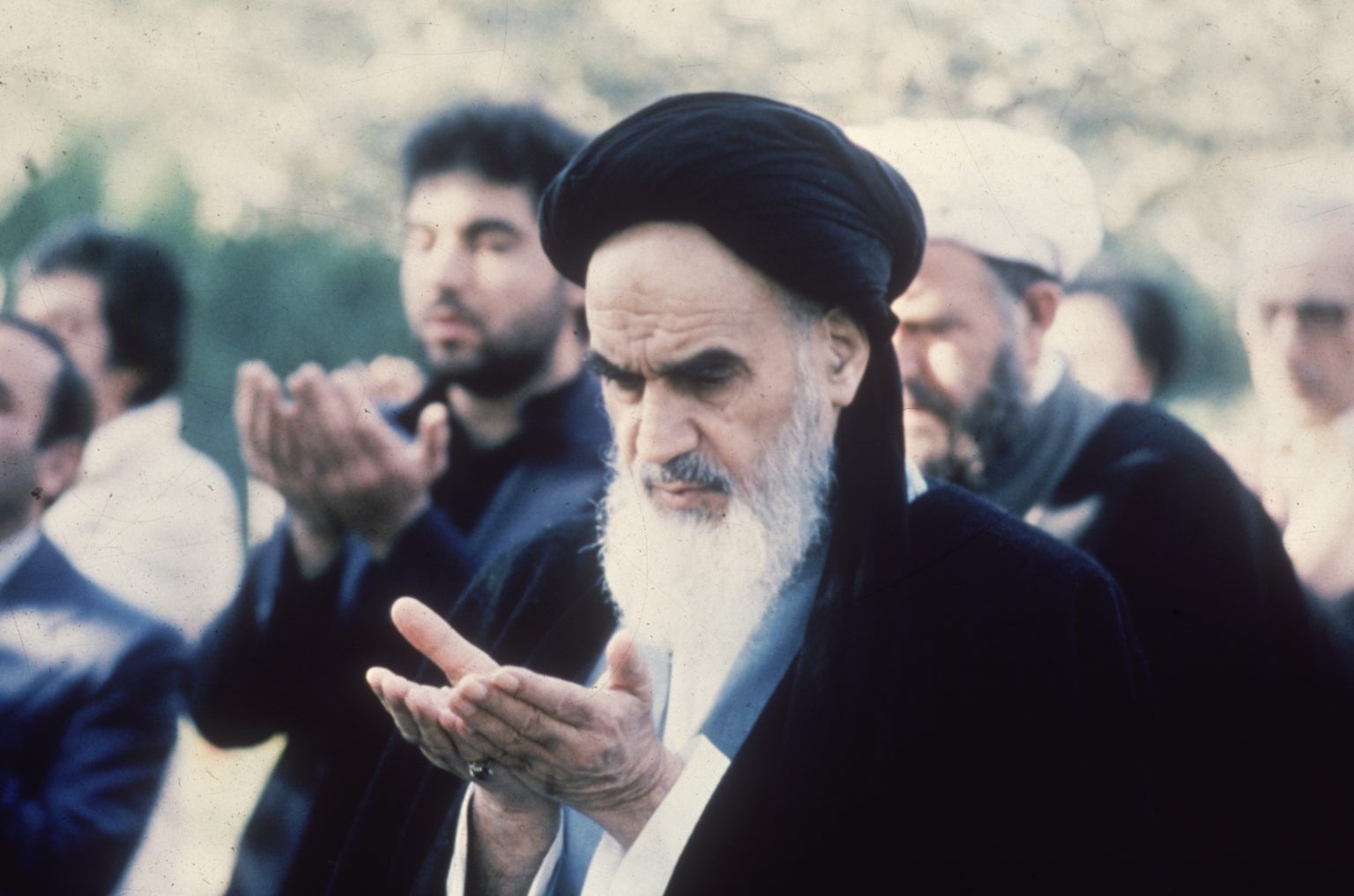

It had started to seem in recent years that the Rushdie affair could be consigned to the past. Yes, the fatwa itself, the assassination order issued by the long-dead Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, still stood. The multimillion-dollar bounty on Rushdie’s head was even increased in 2016. But the Iranian government had tried to draw a line under the affair back in 1998, with then president Mohammad Khatami telling a group of journalists at the United Nations that ‘We should think of the Salman Rushdie issue as completely finished’.

Rushdie himself had been understandably keen to put that part of his life behind him, too, telling one journalist in 2015 that ‘I don’t want to talk about that shit’. His public appearances over the past couple of decades have become more frequent and certainly less furtive. The event at which he was attacked, for instance, was widely publicised – a far cry from the 1990s, when even his friends were rarely told in advance that he would be visiting them.

Moreover, as many have remarked over recent years, the book burnings, protests and the fatwa itself all seemed to belong to a very different era. The fatwa emerged at a time before Islamist violence had become a dismal staple of global affairs. A time before al-Qaeda had flown terror into the heart of America. A time before ISIS had plumbed new depths of barbarism. As one Columbia University academic put it in 2019, on the 30th anniversary of the fatwa: ‘Who still remembers, or cares to remember, or cares at all about the “Salman Rushdie affair”?’

That sense that the Rushdie affair was firmly a matter of the past was clearly misplaced. And not just because Rushdie himself now lies in hospital, Khomeini’s lethal edict ever so nearly executed three decades on. But also because we are still living with the consequences of those strange, transformative days at the tail-end of the 1980s.

For the fatwa against Salman Rushdie marked a crucial turning point, internationally and domestically. It helped to transform Islam, in the eyes of some, from being largely a matter of conscience, a private affair, into a very public, politicised identity. It was the moment when being a Muslim, particularly among the young, started to become less an act of faith than an act of self-expression – a way of being authentic, of being true not so much to Allah, but to oneself.

And it was the moment when ‘Muslim’ became a global identity, too. An identity that could transcend and take priority over the older local, class and national solidarities through which Muslims might once have understood themselves.

In particular, it was the moment when a Muslim identity demanded recognition, legal protection and, in the hands of some who felt wronged, violent retribution.

The geopolitics of the fatwa

The role of Saudi Arabia and Iran in the Rushdie affair, and the impact they had on the development of this new distinctly Muslim identity politics, cannot be downplayed.

Although India was the first nation to ban The Satanic Verses – on 5 October 1988, just nine days after the book’s publication – it was a network of largely Saudi government-funded parties and groups that first started trying to exploit the alleged apostasy of Rushdie’s novel. After the Indian government’s ruling, members of the Saudi-backed Jama’at-i Islami – a fundamentalist Islamist party founded in 1941 in what was to become Pakistan – sent photocopies and faxes of selected, offending passages from The Satanic Verses to 45 embassies of Muslim countries and over 400 organisations worldwide. Among the latter were the Saudi-funded Islamic Foundation, based in Leicester, and assorted other British activists.

From October 1988 onwards, this Riyadh-backed network in Britain, urged on by Jama’at-i Islami, agitated and organised against The Satanic Verses. This led first, on 11 October 1988, to the formation of the UK Action Committee on Islamic Affairs (UKACIA). The UKACIA’s joint convenor, Iqbal Sacranie, who was later to become head of the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), said that ‘death, perhaps, is a bit too easy [for Rushdie]’. A UKACIA circular described The Satanic Verses as the ‘most offensive, filthy and abusive book ever written by any hostile enemy of Islam’.

By 21 October 1988, several hundred thousand Muslims had signed a petition protesting against Rushdie’s new novel, and calling on its publisher, Penguin, to withdraw it. Penguin stood firm and the British government remained unmoved. On 27 October 1988, UKACIA wrote to all the ambassadors of Muslim nations in London calling for the book to be banned. This appeal found its way into the hands of Akhondzadeh Basti, the Iranian charge d’affaires, who forwarded it to Tehran.

At this stage, however, Iran’s theocrats seemed uninterested in what appeared at the time to be a rather confected controversy over a book. The Satanic Verses was even given a review in an Iranian newspaper later that autumn. It was critical but hardly incendiary. Not that this was really a surprise. Strange as it is to think now, Rushdie was actually in favour among Iran’s ruling elites during the 1980s. In a nation in which nearly 4,500 authors, including most of Iran’s own writers and poets, had been placed on an official blacklist since 1986, that was quite something. As Index on Censorship recalled at the time of the fatwa, Rushdie’s first novel, Midnight’s Children (1981), had been translated into Persian and was critically acclaimed in Iran as ‘a cry of the heart against the consequences of Western colonialism’. And Shame (1983), Rushdie’s second book, had, if anything, been even better received, picking up an award in an Islamic literary competition – an achievement all the more remarkable given that Shame was highly critical of certain Islamic practices, especially with regard to women.

Tehran’s initial silence over The Satanic Verses tells us something important about the Rushdie affair – that the decision to issue the fatwa was driven more by the internal politics of Iran and its regional rivalry with Saudi Arabia than it was by any theological concerns. After all, if The Satanic Verses really was the insult to Islam that Iran was later to claim it was, why did it take until February 1989, nearly six months after the novel was first published, for Iran’s clerics to make their move? India had already given them fair warning that this was a supposedly blasphemous novel, and that to even encounter just a few sentences from it would surely cause deep spiritual injury. And yet the ayatollah, the supreme leader of an Islamic republic no less, seemed content to let the matter rest.

That changed in February 1989, when Khomeini’s domestic political struggles came to a head. The Islamic Republic was just 10 years old in 1989. And by then it already faced significant, perhaps even existential problems. It had just emerged, without success, from a cataclysmic eight-year-long conflict with the Western-backed forces of Iraq – a war that had cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Iranians. Food and fuel were being rationed and the Iranian people were becoming restive. This discontent was now generating rifts among Iran’s clerics. A growing reform-minded faction, hopeful of ending Iran’s punishing international isolation, was pushing for Iran to transition from a revolutionary state into a more normal state – one that combined secular with theocratic elements.

Furthermore, Iran’s great rival, Saudi Arabia, was making up ground on Iran, promoting itself as the true representative of Muslims worldwide, along with its ‘Wahhabi’ version of Islam. Khomeini’s Iran was in a bind.

Two events in early 1989 prompted Khomeini to make his move on The Satanic Verses. The first was a thousands-strong protest in the English mill town of Bradford, on 14 January, in which the novel was attached to a stake and set on fire, the images of which were broadcast worldwide. And the second arrived in Islamabad, Pakistan on 12 February, when a crowd of some 10,000 took to the streets in protest against the The Satanic Verses and set fire to the American Cultural Centre. Five protesters were killed and many more injured.

Khomeini saw the unrest stirred by The Satanic Verses as an opportunity to shore up his authority at home – by trying to galvanise Muslims abroad. It was a chance to challenge Saudi Arabia in the battle to become the standard-bearer for global Islam. So it was on Valentine’s Day 1989 that Khomeini, despite never having read the book, called upon ‘all zealous Muslims of the world’ to ‘execute’ the author of the The Satanic Verses ‘and all those involved in the publication who were aware of its contents wherever they may be found’.

The fatwa was transformational. In addressing ‘all zealous Muslims of the world’, Khomeini effectively extended his authority beyond the borders of even Islamic nations. It was a transnational, globalising appeal that potentially freed individual Muslims from their national and local jurisdictions. But not only did it globalise what it meant to be Muslim, it also politicised it. It presented being a Muslim as contingent on opposing The Satanic Verses, on expressing support for the fatwa – and, ultimately, on acting against those who insult Islam.

Khomeini’s audacious move may have been cynical, fuelled largely by his regime’s own domestic struggles. But its impact was international. It impelled the emergence of a new species of sometimes violent identitarianism within Western society. Being a Muslim was now, for those who answered Khomeini’s call, a political cause.

A new Muslim identity

The fatwa was, as one academic puts it, central to the formation of ‘a pan‑Islamic Muslim identity transcending ethnic origins’. But it did not create this from nothing. Rather, it played upon and exploited an already existing demand for recognition, especially among some young Brits, whose parents and grandparents first arrived from Pakistan, India and Bangladesh to fill low-paid jobs during the postwar boom of the 1950s and 1960s.

There were several overlapping factors at play that made these younger generations particularly receptive to Muslim identity politics: the multicultural policies introducted by local authorities in response to the riots of the 1980s; the seeming failure of class-based, left-wing politics to tackle racism; the influence of New Left, especially Black Power-style ideas about self-organisation, independent of white people; and, deeper still, Western society’s ever growing emphasis on the importance of individual authenticity, of being true to who one really is. These combined to encourage some young British Pakistanis, Indians and Bangladeshis to increasingly want to conceive of and be true to themselves in narrower ethnic terms, and, at a political level, to want to assert and defend minority cultural and ethnic rights. That is, they were already primed to think in identitarian terms.

It should be said that religion was not a major factor before the Rushdie affair. Many of those younger British Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and Indians who were increasingly thinking of themselves in terms of cultural difference and authenticity, did not privilege their Islamic backgrounds. Many were not even practising Muslims.

Indeed, this was one of the most striking aspects of the ever growing protests against The Satanic Verses during the late 1980s and 1990s. The increasing presence on them of precisely these young, formerly non-religious men, wearing jeans and t-shirts. They didn’t stop yelling when the elders, in their more traditional dress, would kneel down to pray. And they didn’t appeal, as their elders did on less excitable placards, to a British sense of fair play. Because they were motivated by something different. By a sense of grievance and resentment – a sense that they themselves, in their innermost, authentic being as born-again Muslims, were under attack. Not just from a few paragraphs in the The Satanic Verses. But also from all those who failed to recognise the injury done to them by Rushdie’s words. As the journalist Malise Ruthven noted of a 1990 rally in Hyde Park, ‘The most murderous placards were being carried by these non-observant [young men]’.

It was as if the fatwa brought to the surface and then supercharged a demand for recognition that had long been simmering among a younger, disillusioned generation. It gave it a form, in the shape of a global Muslim identity, and an apparent justification, in the shape of the wrongs visted upon Muslims around the world by arrogant Westerners. ‘It was the Rushdie controversy that forced us into the open [as Muslims]’, recalled one protester reflecting on the Rushdie affair in 2002.

Many of those who were to later flirt with Islamism recount a similar experience of the Rushdie affair. Take Alyas Karmani, who told the BBC in 2019 that, despite having grown up in a traditional Pakistani household in south London, he had initially little interest in religion as a young man. Instead, he was into partying, clubbing and smoking weed. But, as he put it, the fatwa drove him to ‘re-discover’ his Muslim identity. Not at a mosque, but among fellow young Muslims, newly self-identified as such by the fatwa: ‘That’s why I always say I am one of Rushdie’s children.’

Others followed an even more troubling trajectory. Anjem Choudary, for instance, used to hang around activists for the Socialist Workers Party in the late 1980s. After the fatwa, he became a committed, anti-Western ideologue, draped in the garb of Islam.

Theirs was not a traditional experience of religion. It was an experience apart from clerical or state institutions – an individuated experience, as much about self-discovery and authentic self-expression as it was about the Koran or attending the local mosque. As one academic puts it, this particular idea of Muslimness represents an ‘affirmative reconstruction of identity’. And it’s a form of self-identification that, like the fatwa itself, derives its infernal energy from the existence of an offence-giver or victimiser, which is often reducible to the West itself.

The fatwa effectively marked the point when an identitarian version of Islam entered the bloodstream of Western and especially British society. From that point on, some among the younger generations from immigrant communities began to see themselves almost entirely in the terms initially laid down by the ayatollah’s fatwa. To be a ‘zealous Muslim’ was to dramatise offence, to publicly perform the role of the offended. It was to hunt down, metaphorically and sometimes literally, those who ‘insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims’. Those who offend against one’s innermost sense of oneself as a Muslim. Often with deeply illiberal and sometimes murderous results. In this, they have been encouraged by an identitarian quangocracy, much of which emerged during the Rushdie affair. And they have been emboldened by an increasingly identitarian establishment that all too often agrees that words deemed hurtful, like those of Salman Rushdie, are worthy of punishment.

The legacy of the Rushdie affair is very much with us today. Not just in the barbaric Islamism of the extremes, but at the heart of a more socially acceptable Muslim identity politics, too. It is ‘Rushdie’s children’ who today warn endlessly of ‘Islamophobia’ and who talk up alleged anti-Muslim sentiments. And it is Rushdie’s children who want an author punished for writing a book that hurt their feelings.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.