No, Colin Kaepernick, the NFL is not just like slavery

Who knew the life of a multimillionaire sports superstar could be so oppressive?

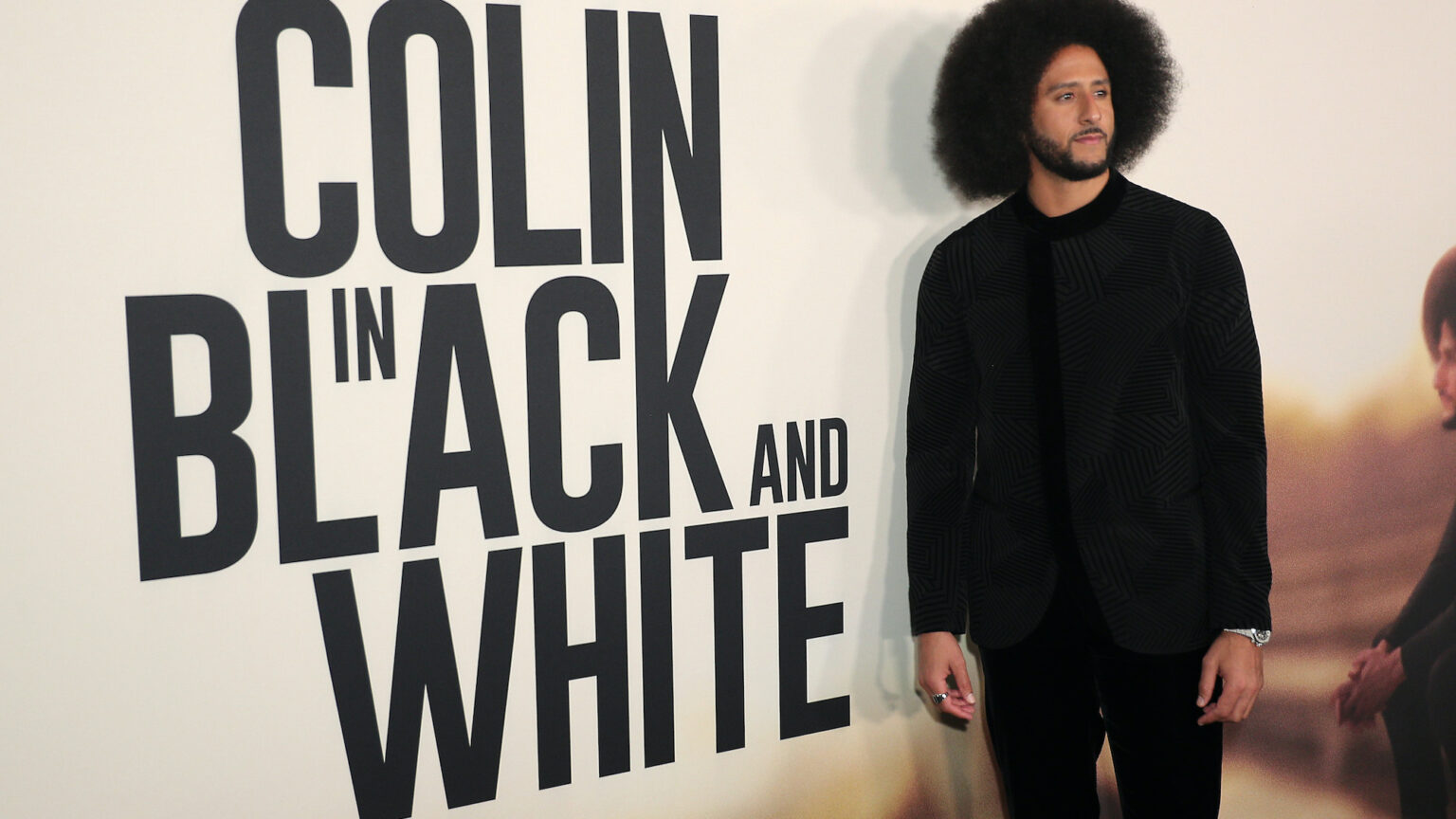

The first episode of the new Netflix series, Colin in Black & White, opens with former National Football League quarterback and current social-justice activist Colin Kaepernick comparing the NFL Scouting Combine, where NFL teams assess prospective players, to a slave auction.

‘Before they put you on the field’, Kaepernick says, addressing the camera, ‘teams poke, prod and examine you, searching for any defect that may affect your performance. No boundary respected. No dignity left intact.’

Then, to really drive the point home, the black football players who are being examined around Kaepernick exit the field, walk past him, and go back in time. Now wearing loincloths and chains, these black men are transformed into human chattel and auctioned off. At the end of one sale, the slave dealer and a football coach bend space and time to shake hands. White hands.

This vignette makes for a powerful, jarring visual – I wondered, how much money did Netflix spend to bring this weak-ass metaphor to the screen?

If you think I’m wrong, if you happen to agree with the analogy Kaepernick is making, just try this thought experiment: what are some of the ways the NFL is not like slavery?

As other critics have pointed out, there is an obvious difference between slaves and NFL athletes. You know, the difference between unpaid slave labour and free men voluntarily trying out for professional sports teams with million-dollar signing bonuses.

You don’t have to know much about American football or sports in general to understand that all the poking, prodding and examining is in the interest of the team owners and even the players themselves. According to the NFL, players ‘are also checked for blood pressure, heart and organ function, undergo a series of x-rays and are tested for their flexibility’. Apparently, there are psychological evaluations, too. But – it being football and all – I’m going to guess that those evaluations don’t carry as much weight as whether a player can run the 40-yard dash and smash through other hulking men.

Dave Zirin, sports editor at the Nation, reminds us in a tweet that ‘comparisons of the NFL combine to slavery have been made by players for decades. Only reason this is getting heat now is [because] Kaepernick said it and there’s [a right-wing] backlash now against any discussion of the realities of racism.’

This made me think: how does the NFL get away with only subjecting its black players to the combine? Colin in Black & White and Zirin’s defence of it would have you believe that is really what happens. Of course, when it comes to the combine, white players also have ‘no boundary respected, no dignity left intact’. Quarterback Tom Brady’s combine was so embarrassingly bad that the only way for him to restore his dignity was to go on to win six Super Bowls.

Just like the NFL / slavery comparison, none of Kaepernick’s commentary in Colin in Black & White is new, either. In the early days of Kaepernick’s public activism I joked that you could always tell which Rage Against the Machine album he had just listened to. When he called for the release of convicted cop killer Mumia Abu-Jamal, I figured he was up to Rage’s The Battle of Los Angeles.

Colin in Black & White is part biopic, too. Adult Kaepernick tells the story of his high-school years as a struggling star athlete whose sole mission in life was to be a quarterback. Nothing else would do. The Chicago Cubs even offer him a lucrative contract to pitch for them, but he repeatedly turns them down in almost every episode of the series.

Kaepernick’s is the story of the young phenomenon not having any fun and not being worshipped as the sporting god he is. And he uses his own life to talk about white privilege and microaggressions, share unrelated moments in black history and highlight prominent black figures from it. It’s a strange brew of storytelling.

‘I couldn’t rebel because I didn’t know how’, he admits about his younger self. ‘But now. Now I know how. And I will.’ Hence his willingness to take a knee during the national anthem and, as a Nike brand ambassador, ‘Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.’

I wouldn’t be the first to call out Kaepernick for his willingness to speak out against injustice and modern-day ‘slavery’ at home in the US, while remaining silent on China’s human-rights violations. And we all know how those Nike swooshes get stitched on all that corporate apparel.

In Colin in Black & White, you get the sense that Kaepernick is straining to connect himself with black history and with today’s black struggle. His biography shows why this is such an uphill battle for him. He is biracial after all. His biological mother was white, his biological father black, and he was adopted into the white Kaepernick family who raised him in Turlock, California (a place, he admits, that has a ‘scarcity of black people’).

There is a running gag in the series where the food his adopted mother serves never has enough seasoning – because, as per the stereotype, white people don’t season their food. By contrast, the ambrosia made by the black people destiny introduces to young Colin is always perfectly seasoned.

For some reason Kaepernick never embraces his ‘white side’ or even acknowledges it. If he did, he might not be able to get away with lines like, ‘As long as we need the white man’s stamp of approval, our fate may be in the hands of those who don’t think we qualify’. And ‘Maybe they didn’t want us to see our beauty, because if we did, if we controlled our own narrative, we’d be unstoppable’.

From the way Kaepernick depicts the white people in his life, I can understand why he wouldn’t want to identify with them. The white people he has drawn are all one-dimensional, cartoonishly so – they lack seasoning, if you will. They’re either racists microaggressing on young Colin or authority figures trying to get him to bend to their will.

Even his poor adopted parents are written as if they were aliens. There’s a lot of moments where you’re supposed to think: ‘Oh, they really don’t understand black people.’ But the way they are portrayed, they don’t seem to understand people at all. There is one scene in which Colin is driving his parents to a baseball tournament and they are pulled over by a policeman. His adopted father does the very unfatherly thing and lets his son do the talking. Spoiler: the cop reaches for his gun. The vignette is about as subtle as anything else you’ll see in Black & White.

In the final episode – titled, ‘Dear Colin’ – Kaepernick writes a letter to his young self. Magically, as if bending time and space again, his young self reads that very letter. It ends with: ‘Trust your power. Love your blackness. You will know who you are.’

But if you don’t know who you are, you have six half-hour episodes to make yourself up.

Lou Perez is a comedian, producer, host of The Lou Perez Podcast and author of the forthcoming book, That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore. Follow him on Twitter: @TheLouPerez

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.