Long-read

How Big Tech took over

The establishment outsourced censorship to the private sector – and created a tyranny.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

‘We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity.’

These are the words of cyberlibertarian John Perry Barlow in his ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’, penned in 1996. This bombastic document articulates much of the promise idealists once saw in the internet. Above all, it was supposed to unleash free speech and self-expression beyond

anything previously imagined.

So central was free speech to the mythos of the online world that when the tech giants we know and fear today began to emerge, turning a once anarchic space into hugely profitable businesses, they often appealed to that very principle. Free speech, for these would-be oligarchs, provided them with some semblance of deeper purpose.

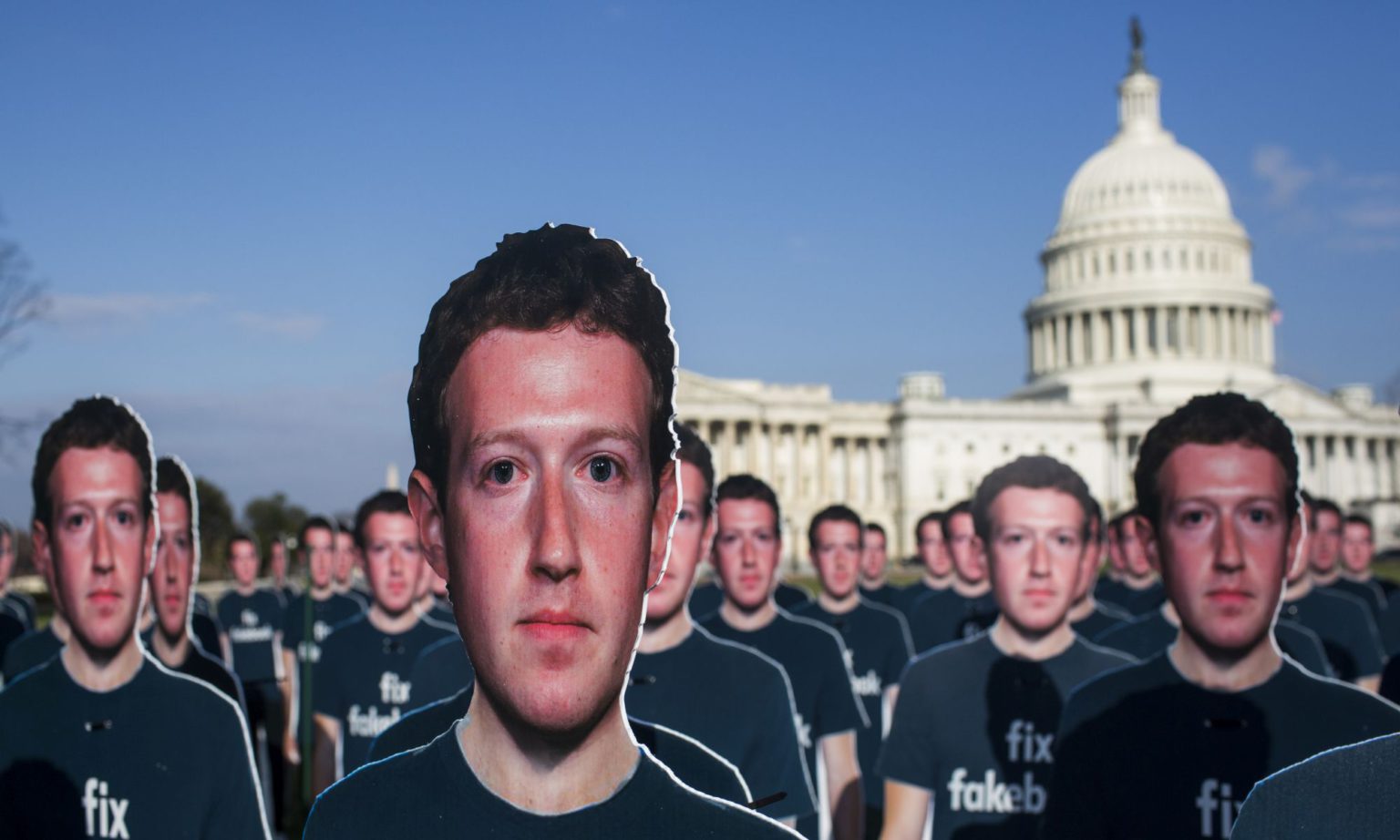

In 2012, Twitter’s UK general manager, Tony Wang, famously dubbed the social network ‘the free speech wing of the free speech party’. ‘Giving people a voice’ is the somewhat more bloodless formulation preferred by one Mark Zuckerberg when describing the moral mission of his social-media behemoth, Facebook.

Last week, those two companies banned Donald Trump, the still sitting president of the United States, from their platforms indefinitely, effectively depriving a democratically elected leader of his access to what now constitutes the public square. They crossed a line few ever thought they would cross, and reminded us just how far that old dream of the free internet now is from the authoritarian, corporate reality.

In the wake of the storming of the Capitol by Trumpist rioters last week, Twitter and Facebook claimed Trump’s ongoing presence on their platforms would incite more violence. But the mental gymnastics required to justify that claim made clear something else was going on. In its rationale for suspending Trump, Twitter cited a tweet in which he confirmed he would not be attending the inauguration of Joe Biden, saying it could be interpreted as a coded invitation to attack it.

In truth, the historic decisions taken by Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and others last week were the culmination of a years-long campaign, waged from inside and outside these tech firms, to deplatform Trump. Supposed liberals and leftists have accused him of spreading hate and misinformation, and routinely heaped pressure on these companies to intervene.

For a long time, Big Tech just about held out against the tide – even as the platforms’ policies on policing speech became more and more prohibitive. Trump was still the president, after all. Warning labels and fact-checks were slapped on his most controversial posts instead, itself a remarkable intervention. That would have to suffice, it seemed, until he left office and would no longer be afforded special protection.

Perhaps it was the pressure of the moment. Perhaps the Capitol storming simply gave Twitter and Facebook an excuse. But those suggesting these bans were purely the result of the cool-headed application of Facebook’s and Twitter’s guidelines are deluding themselves, as are those who don’t seem to see the terrifying precedent this all sets.

These tech firms, which once claimed the mantle of free speech, have now become instruments of political censorship – arguably the most powerful the world has ever known. So powerful, in fact, that even the highest elected office in the free world is not enough to protect you from them. The question is: how did we get here?

The political leanings of Silicon Valley are at this point beyond doubt. An analysis by Wired ahead of the November election found that 95 per cent of donations by employees at the six big tech firms – Alphabet (parent company of Google), Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and Oracle – went to Joe Biden.

But to suggest that these companies were desperate from the outset to inflict censorship on their ideological opponents, to assume the role of moral arbiters and ministers of truth, is to ascribe to them a moral substance that is probably beyond them. In the end, they wanted to make money. And they have always been acutely aware that acquiescing to the calls for them to censor more and more content would plunge them into political controversy.

But acquiesced they now have. In recent years, at remarkable speed, Big Tech has extended its censorious writ over more and more aspects of online discussion. And in doing so these firms have offered a perfect case study in how swiftly censorship grows as soon as the principle is compromised.

There was arguably no golden age for unfettered free speech on these platforms. As soon as the digital public square became dominated by a handful of billionaires, the days of the free internet were numbered. But over the past five years in particular, censorship on these sites has been turbocharged in response to a slew of moral panics.

From 2016 onwards, a succession of hard-right figures were banned by the big platforms over alleged hate speech, from alt-lite troll Milo Yiannopoulos to anti-Islam thug Tommy Robinson to comical conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. The old liberal arguments against censoring bigots – that the answer to bad speech is more speech, that censorship only drives hate underground – were dismissed, if indeed they were ever made.

Commentators and politicians demanded scalp after scalp. The taste for censorship was insatiable. And as hate-speech policies widened, more respectable voices were caught up in them. One was gender-critical feminist Meghan Murphy, permanently banned from Twitter for the crime of ‘misgendering’ an alleged sex offender.

Even amid all this, Big Tech tried to hold to a series of increasingly sketchy lines. In 2018, Mark Zuckerberg said, on record and unprompted, that it wasn’t Facebook’s job to censor Holocaust denial, however offensive he as a Jewish man found it. He did not want to rule on what is and isn’t true. When Alex Jones was booted off Facebook that same year, a spokesperson was at pains to say this was over Jones’ alleged ‘hate speech’ and ‘glorification of violence’ – not his madcap claims that the Sandy Hook massacre was a ‘false flag’ or 9/11 was an inside job.

But the logic of censorship is always towards more censorship. And Silicon Valley came under increasing political pressure to clamp down on online hate and misinformation, which leading Democrats in the US believe was instrumental to Trump’s election in 2016 – baffled as they are by the prospect that some voters might have simply preferred him to Hillary Clinton.

Last year, Joe Biden told the New York Times that Facebook was ‘propagating falsehoods’, pointing to attack ads he said had been run against him by Russians and Republicans. He called for Section 230 – which protects tech platforms from liability for what their users post – to be revoked.

When now vice-president-elect Kamala Harris was seeking the Democratic nomination, she also took aim at Facebook and Twitter over so-called hate speech. ‘We will hold social-media platforms accountable for the hate infiltrating their platforms’, she said.

Politicians hauled Zuckerberg et al before Congressional hearings, demanding that they do more to fact-check and censor, under the looming threat of their businesses being regulated or broken up. But time and again Democrats seemed less concerned about these firms’ monopolistic power and more about their apparent hesitance to wield it to the ends of censorship.

2020 was the year this all came to a head.

First, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the big platforms abandoned any prior concerns they might have had about becoming the Ministry of Truth. YouTube began banning any content that deviated from the advice of the World Health Organisation. Facebook started doing pandemic fact-checking and tried to depress the spread of Covid-denying posts, but it was soon banning conspiracy theorists wholesale. (Zuckerberg’s uncharacteristically liberal approach to Holocaust denial was also dropped.)

Then came the US presidential election. And with some dark irony, fears that Trumpist misinformation would swing the result led Big Tech to make one of its most sinister interventions into electoral politics up to that point: the censorship of a mudslinging New York Post exposé about Joe Biden’s notoriously dodgy son, Hunter. Twitter locked the Post, America’s oldest daily newspaper, out of its Twitter account. Users were prevented from sharing the story, even in private messages. Facebook announced it was ‘reducing’ the story’s ‘distribution on our platform’, in line with ‘our standard process to reduce the spread of misinformation’.

If Big Tech had simply, arrogantly assumed the right to restrict free speech and to meddle in democratic politics, that would have been bad enough. But the truth is that, at each turn, these corporate giants have had this role foisted upon them by a liberal establishment rattled by the Trump revolt and increasingly given to hysteria.

For all the liberal elites’ posturing against these monopolistic firms, they have handed Big Tech the moral authority to police the public square. The revolving door between Silicon Valley and the Democratic Party, not to mention the Big Tech alumni staffing Biden’s team, suggests the incoming administration is more than comfortable with this arrangement for now.

Even so, liberals and leftists are already starting to wake up to the danger Trump’s social-media bans pose, and the shadow they could cast over politics in the future. In a recent New York Times column, Michelle Goldberg sums up the now common doublethink: ‘I find myself both agreeing with how technology giants have used their power in this case, and disturbed by just how awesome their power is.’

Other world leaders have, as you might imagine, found it all unsettling. A spokesman for German chancellor Angela Merkel – no free-speech advocate herself – said the social-media clampdown was ‘problematic’. Mexican president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador went further, likening it to the Inquisition.

Most strikingly, the Polish government has said it will draft legislation to limit Big Tech censorship. Polish law is hardly free-speech fundamentalist, nor is its governing Law and Justice Party particularly liberal. Still, this nascent, sovereignist pushback against Big Tech censorship – which often goes well beyond the censorship practised by national governments – may be a taste of things to come.

When John Perry Barlow wrote his declaration 25 years ago, his aim was fixed squarely on the state. ‘Governments of the Industrial World’, he thundered, ‘I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.’ But in Western democracies today, at least, the primary threat to online free speech comes not from national governments, but from a Silicon Valley oligarchy that was elected by precisely no one.

How to challenge Big Tech censorship is an issue we believers in free speech will be grappling with for years to come – alongside the state censorship that has only grown in Britain and elsewhere of late. But perhaps the democratic nation state, so often painted as the problem, will prove to be part of the solution.

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

All photos by: Getty Images.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.