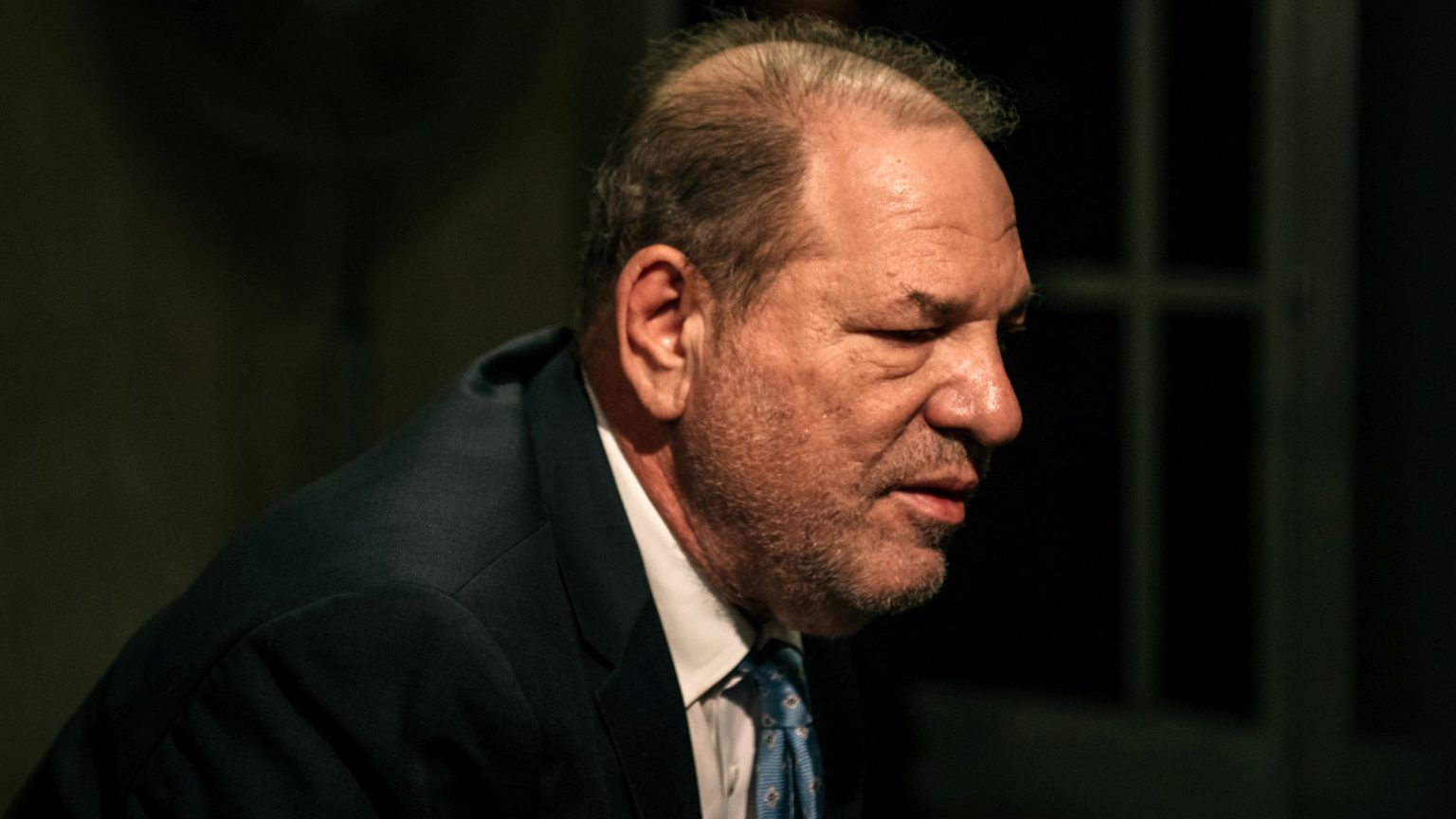

Harvey Weinstein: justice has been done

But the #MeToo movement has done serious damage to justice in other ways.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

More than two years after it first took off, the #MeToo movement finally has its prize. Yesterday, Harvey Weinstein was found guilty of raping one woman and sexually assaulting another. He now faces up to 29 years in jail. It is good that the accusations against Weinstein were put before a jury and it is good that justice has now been done. Few will be shedding tears at the shamed movie mogul’s conviction.

All around the world, campaigners, actors and journalists are celebrating Weinstein’s incarceration, not just as an example of the legal process successfully functioning, but also as a triumph for the #MeToo movement. Actresses such as Rosanna Arquette and Ashley Judd, who were among the first to come forward with accusations against Weinstein, have praised the bravery of the women who testified against Weinstein in court, as well all the #SilenceBreakers who spoke out about sexual assault. Tarana Burke who coined the phrase #MeToo, has described the reverberations of Monday’s verdict as extending far beyond Hollywood. The New York Post declared the guilty verdicts ‘a huge win for #MeToo’, while the BBC labelled Weinstein’s conviction ‘a victory for the #MeToo movement’.

But the long-awaited verdict is not the huge victory for women everywhere – or indeed for the specific women who came forward with allegations – that jubilant commentators would have us believe. And in the rush to celebrate, serious questions about the role of the #MeToo movement in actually hindering Weinstein’s prosecution are being overlooked.

Back in October 2017, in the days and weeks after the #MeToo movement first took off, at least 100 women alleged some form of sexual assault or mistreatment at the hands of Weinstein. Yet far fewer have taken their accusations to police or lawyers. There has been a great deal of talk about Weinstein’s use of non-disclosure agreements and women being too afraid to speak out. But a substantial number of women are, it seems, happy to have their stories discussed in the press and on social media but are not prepared to face cross-examination in a courtroom.

This matters because the sheer weight of allegations and the scale of media coverage surrounding Weinstein may have prejudiced the jury. From the very first #MeToo tweet, the case against Weinstein became merged with claims of sexual harassment made by women all over the world. That was a lot for one man to stand trial for and, unsurprisingly, Weinstein’s lawyers are now appealing his conviction in part on these grounds.

In court, the prosecution lawyers called witnesses who alleged abuse at the hands of Weinstein, but whose accusations were not included in the charges he faced. Their aim was to establish a pattern of behaviour, to paint Weinstein as a predator. This form of argument was mounted in the trial of Bill Cosby, but has not traditionally been used in legal proceedings that seek to try only specific crimes. This does indeed follow a pattern: right from the start, the #MeToo movement has looked to overturn long-standing principles of justice, including most notably the presumption of innocence. Under the edict of #MeToo, the imperative to believe all women meant that people were tried, found guilty and sentenced in the court of social media. This has had devastating consequences for individuals who have been accused of serious crimes, and has potentially contributed to the tragic suicides of Labour politician Carl Sargeant and, most recently, Caroline Flack.

Weinstein faced just four charges. He was found guilty of committing a criminal sexual act and third-degree rape, but he was acquitted of two counts of predatory sexual assault. The jury took four-and-a-half days to reach their verdict. The acquittals, the length of time the jury spent deliberating, and the small number of women that ultimately followed through with their accusations, suggest a truth that the #MeToo movement was never able to acknowledge – that sometimes sex is very clearly non-consensual and a woman has been raped, but that other times the issue of consent is not at all clear. Weinstein was a powerful man who could make or break women’s careers – a fact he no doubt exploited. But in an industry that privileges glamour and sexuality, there are also women who choose to use their beauty to their advantage. Some women, perhaps even some who were physically repulsed by Weinstein, no doubt sought to exploit his desire for them. #MeToo’s inability to recognise this infantilises women and robs them of all agency in encounters with men.

The women who took their accusation against Weinstein to court have every right to celebrate the fact that he has been found guilty and is now behind bars. But beyond this, who has #MeToo helped? Certainly not working-class girls from Huddersfield, Oxford, Manchester or Keighley, who were sexually abused at the hands of men of Pakistani heritage. There have been no #MeToo marches in solidarity with these young victims and no fundraisers to provide for their legal defence.

#MeToo’s pyrrhic victory lies solely in the fact that it has allowed a small group of middle-class, well-educated, elite women with a wealth of opportunities to portray themselves as victims. A tiny proportion of this cohort have gained a public profile from sharing their stories. For all other women, #MeToo has done far more harm than good. With the conviction of Harvey Weinstein, it is time to put an end to the #MeToo movement once and for all.

Joanna Williams is a spiked columnist and director of the think tank, Cieo.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.