Policing what you post – even in private

The case of the Grenfell effigy raises some worrying questions.

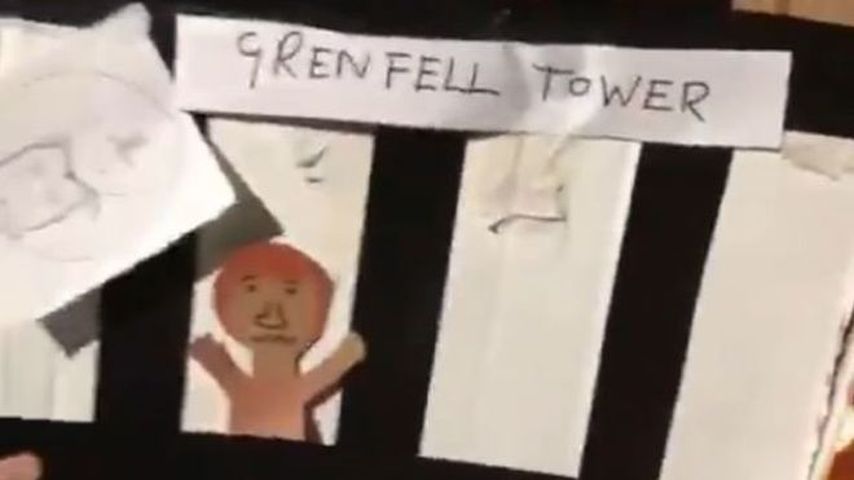

In November last year, at a bonfire party in a south London back garden, some people set up a cardboard model of a block of flats, labelled it Grenfell Tower, placed dark-faced cardboard figures in its windows, and set it on fire. The effigy was filmed on a mobile phone. The video was distributed to members of a few WhatsApp groups. Someone in one of the groups passed it on, and it went viral.

The Crown Prosecution Service, ever determined to keep as close a control as possible over what is said online, threw the book at the host of the party, Paul Bussetti. He was charged with transmitting grossly offensive material over a communications system.

But as it happened, the trial was a farcical anti-climax. It turned out that a bungling CPS had failed to prepare the case properly, or to pass on information that the viral video might have been taken by someone else entirely. The charge was dismissed.

It’s good news that we were spared the spectacle of someone being sent down for something they got up to in their own back garden, regardless of how offensive it was. It could have so easily gone the other way: the magistrate deciding the case was Emma Arbuthnot, who imprisoned the demonstrator who egged Jeremy Corbyn.

Nevertheless, this whole affair remains worrying for anyone interested in preserving the private sphere. The video was vile, and produced by deeply unpleasant people. But it was still a private act. And it would have been far better to ignore it rather than give it so much publicity. Plus it reflects the broader trend for policing online speech.

Bussetti was charged under Section 127 of the Communications Act 2003. This criminalises those who send, or cause to be sent, by means of an electronic communications network material that is ‘grossly offensive’. It dates back, as Lord Bingham notes, to the Post Office (Amendment) Act 1935, which made it an offence to send any message by telephone which is ‘grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character’.

Section 127 extended this to the entire online world. And it has since become a catch-all crime for almost anything on the internet that the authorities disapprove of and choose to prosecute. After all, what is and isn’t grossly offensive is any magistrate’s guess.

What’s more, despite the government’s commitment to treating online and offline crime equally, Section 127 effectively restricts online speech to such a degree that there is no equivalent restriction that exists offline. It must go.

But there is more to the Bussetti case than that. Previous prosecutions, including that of Count Dankula over the ‘Nazi pug’ video, have in general been brought in respect of online material broadcast publicly for anyone to see – if they so choose. What Bussetti did, by contrast, was an entirely private matter. Before someone passed it on, the video of the burning effigy was sent to two closed WhatsApp groups, consisting of no more than 20 people in total.

In other words, we’ve now reached a situation in which you are liable to have your collar felt for things you post to a closed group of friends, and which somehow becomes public. That is a prospect that ought to frighten anyone.

Andrew Tettenborn is a professor of commercial law and a former Cambridge admissions officer.

Picture by: YouTube.

Rod Liddle and Brendan O'Neill

– live in London

Podcast Live, Friends House, London, NW1 2BJ – 5 October 2019, 2.30pm-3.30pm

To get tickets, click the button below, then scroll down to The Brendan O'Neill Show logo on the Podcast Live page.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.