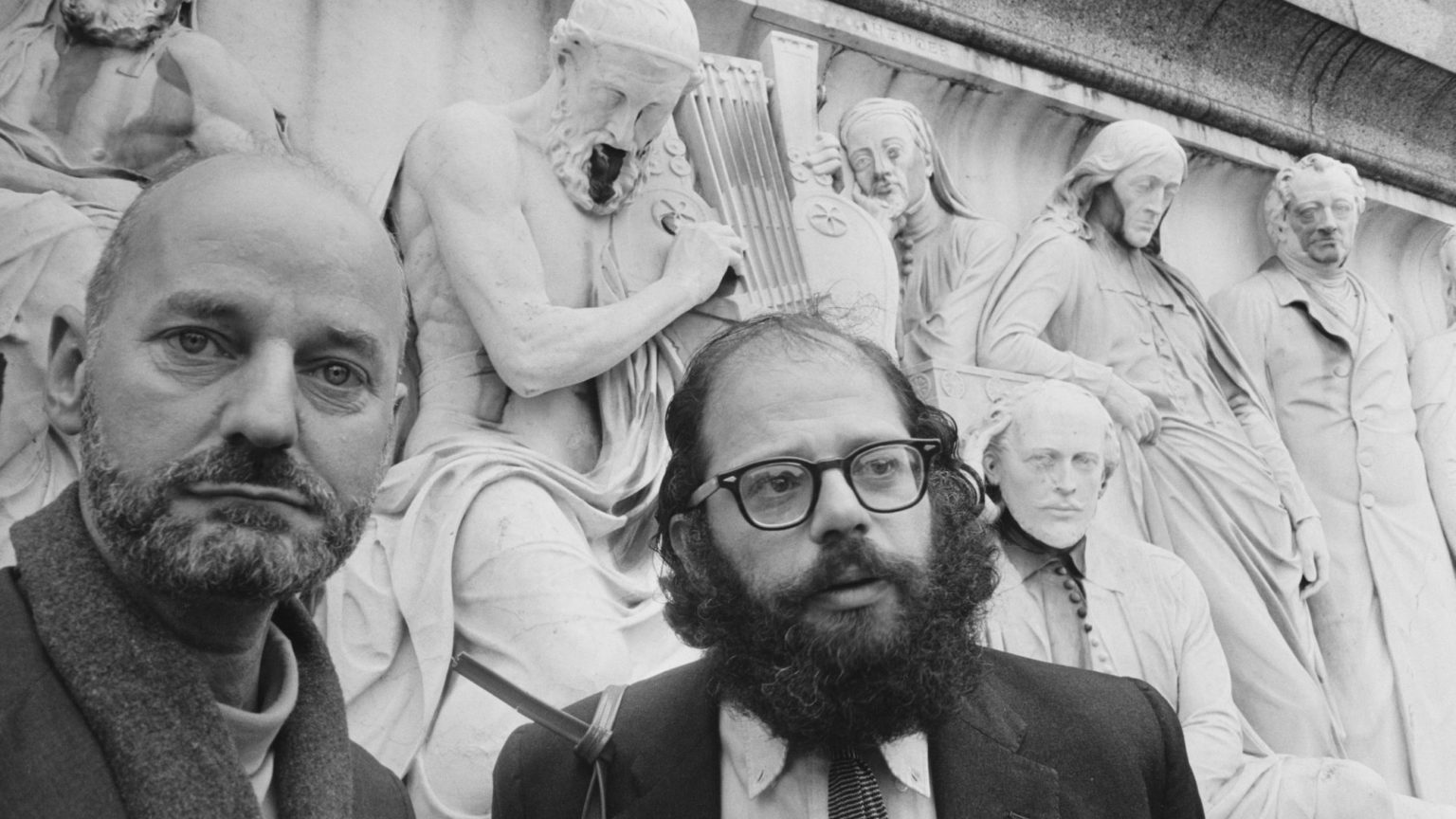

The fight to publish Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’

In 1950s California, publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti took on the censors – and won.

In The People v Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’, Ronald Collins and David Skover take us to the 1950s, and a California on the verge of social change. At the heart of their uplifting story is the business acumen and literary idealism of Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Ferlinghetti, now aged 100 and still proprietor of City Lights Bookstore and publishing house, is a seminal figure in San Francisco. He is considered its poet laureate and a great contributor to its cultural life, as a publisher, artist, activist and political renegade. His idiosyncratic blend of environmentalism, anarchism, socialism and artistic freedom has provided generations with inspiration; his poetry, prose and polemic has impressed writers and given them the courage to follow their convictions; his publications have introduced millions of people worldwide to advanced writers.

San Francisco was the West Coast centre for the Beat Generation, a counterbalance to its other centre in New York. On the evening of 7 October 1955, Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Philip Whalen and Allen Ginsberg gathered at a gallery in San Francisco to read poetry at an event called ‘6 Poets at 6 Gallery’ (the sixth poet was either compere Kenneth Rexroth or the spirit of the late John Hoffman, whose work was read by Lamantia). In the audience were Ferlinghetti and Jack Kerouac.

Ginsberg read ‘Howl’, a long unpublished poem he had recently composed. This was not only to be a breakthrough poem for Ginsberg – it was also to be a watershed in American literary culture, shaping a generation’s writing, from prose and poetry to rock lyrics. Yet on 7 October 1955, Ginsberg was virtually unknown to the wider public.

Ginsberg began to read:

‘I saw the best minds of my generation

destroyed by madness

starving, mystical, naked,

who dragged themselves thru the angry streets at

dawn looking for a negro fix.’

Ginsberg chronicled the insanity, death and degradation of his Beat friends – incarcerated, murdered, exiled, starving, drug-addicted, driven beyond endurance into states of wretchedness – and presented them as holy beings made divine and transcendent through an unjust world. Their suffering was a moral posture, a condemnation of a world gone insane through Cold War division, and rife with hypocrisy and injustice.

He also described, with remarkable frankness, drunkenness, drug-taking and casual sex (including homosexual sex), using language that had never before been printed in a newspaper or spoken on radio or in the cinema. His characters were ‘fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists’; his junkies ‘wandered all night with their shoes full of blood / on the snow banks of East River’, looking for warmth and a fix. Influences included street language, criminal argot and Judaic lore, with Ginsberg taking the mantle of a Hebraic prophet in hipster guise. There is much more, too. ‘Howl’ was Ginsberg’s way of mourning his mother’s detention in a mental asylum. And he dedicated it to Carl Solomon, his cousin who was then also being treated in a mental asylum. In a cathartic outpouring of anger, despair and desperate hope, Ginsberg wrenched American poetry into a world of living language and common experience.

The audience was amazed by the intensity and originality of what they had heard. Others were shocked by the vulgarity. It was clear ‘Howl’ was potentially a sensation. It was just a question of how to get the poem out to the public at large.

The next day Ginsberg received a telegram: ‘I greet you at the beginning of a great career. When do I get the manuscript?’ It was sent by Ferlinghetti. He intended to publish ‘Howl’ as part of a series of small paperbacks from City Lights. A shrewd businessman as well as an advocate of literary avant-gardism, Ferlinghetti saw the potentially high rewards for any publisher of such a radical poem. Yet there were high risks, too. From the outset it was clear ‘Howl’ would be a tough test for poet and publisher to get into print under obscenity laws. Howl and Other Poems (comprising ‘Howl’ plus nine other poems by Ginsberg, and an introduction by William Carlos Williams) was slated for publication in 1957. American printers were wary of printing such material, so Ferlinghetti contracted a British printer instead.

When the first copies of Howl and Other Poems reached newspapers and influential luminaries, the reception was generally positive, with critics noting the radical break with tradition that ‘Howl’ represented. When a second batch of copies was posted from the UK to City Lights, the US Customs Office in San Francisco seized the books as obscene. The US Attorney Office then decided not to prosecute City Lights, and so the customs office had no choice but to release the shipment.

But that was not the end of the publisher’s problems. On 3 June 1957, plainclothes police officers purchased a copy of Howl and Other Poems from City Lights Books, and subsequently Ferlinghetti and Murao (the store manager) were charged, under Californian law, with the sale of ‘obscene and indecent’ material. Ferlinghetti was out of town, so Murao alone was arrested and taken to the police station.

If the authorities expected public support, however, they were mistaken. The press came down on Ferlinghetti’s side. So, when Police Captain Hanrahan announced that they had brought charges against Ferlinghetti and Murao in order to protect children, journalists pointed out that using children’s vulnerability to censor books for adults was absurd and authoritarian.

On 8 August 1957, the case came to court before a packed public gallery. The trial – juryless and to be adjudicated by Justice William Brennan – was seen as a battle between generations, political sides and social outlooks. Prosecutors had five main arguments against Howl and Other Poems: it was pro-communism, pro-homosexuality, pro-promiscuity, anti-capitalism and anti-America. Thus the prosecution took the form of a broad political argument rather than a narrow focus upon the use of vulgar language and description of criminal acts. The defence, led by American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Al Bendich, star criminal-defence lawyer Jacob Ehrlich, and civil-rights lawyer Lawrence Speiser, argued that the First Amendment constitutionally protected free speech. The defence against the California obscenity law was that vulgarity on its own was not (legally speaking) obscenity, and that there was no malicious intent on the part of the sellers to sell Howl and Other Poems as a salacious book. Justice Brennan dismissed the case against Murao, as it could not be proved that he had read the book before selling it.

Expert witnesses – authors, English professors and critics – gave testimony on behalf of the defence of Ferlinghetti. Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti and Murao did not testify. The prosecution’s two expert witnesses were weak. The defendant had reason to be optimistic when Justice Brennan retired for consideration.

In the meantime, all the publicity caused ‘Howl’ to become headline news and, as City Lights kept selling Howl and Other Poems during the trial, it went on to become – in terms of poetry – a bestseller. There were negative reviews (‘exhibitionist’, ‘self-righteous’, ‘tireless arrogance’, ‘dreadful little volume’), but many readers responded well to seeing a recognisable urban, modern world in verse. ‘Howl’ became an icon of the emergent counterculture. By the time the verdict was due, Kerouac’s On The Road had become a nationwide literary sensation and the Beats were common currency in the US.

On 3 October, Ferlinghetti was found not guilty. The judge determined that ‘Howl’ had social importance and could therefore not be classed as obscene. ‘The authors of the First Amendment’, stated Justice Brennan, ‘knew that novel and unconventional ideas might disturb the complacent, but they chose to encourage a freedom which they believed essential if a vigorous enlightenment was ever to triumph over slothful ignorance’. Despite being a committed Christian and a social conservative, Justice Brennan concluded that Howl and Other Poems was a lawful publication and that, in this instance, the right to free speech should not be abridged. There was no clear and present danger that ‘Howl’ would incite ‘anti-social or immoral action’. The verdict was celebrated by public and press alike.

In a curious way, the case of ‘Howl’ – full of the righteous anger of a defiant outlaw renegade – led to a demonstration of the decency and impartiality of the part of an American justice system that the poet so despised. Although the trial of ‘Howl’ did not end literary censorship in the US, it vindicated both anarchic artistry and conservative jurisprudence.

The People v Ferlinghetti recounts the story of the court case in an approachable but thorough manner, and draws valuable attention to how uncensored radio broadcast of ‘Howl’ on American public radio is currently impossible due to obscenity regulation, despite the fact that in print, cinema, television and press (and on the internet) such restrictions are non-existent or less severe. Also published is the whole of Brennan’s written judgment, published as an appendix – it is a model of fairness and rational consideration. The People v Ferlinghetti is the complete resource for anyone interested in this landmark case of attempted censorship.

It also provides a timely reminder of the nature of restrictions on free speech. Censors suppress material and use the excuse of protecting the weak and easily upset. The honour of minorities and ‘protecting the vulnerable’ are used as shields by authoritarians so they can impose their worldview upon everyone. Do not permit them that cover. The decision of Justice Brennan shows that under constitutional protection, disinterested judgment can extend protection to controversial art and allow political dissent to be heard, even in a society that is largely conservative.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. Visit his website here.

The People v Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’, by Ronald KL Collins & David M Skover, is published by Rowan and Littlefield. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.