Corbyn’s Labour: Mods or Rockers in Brighton

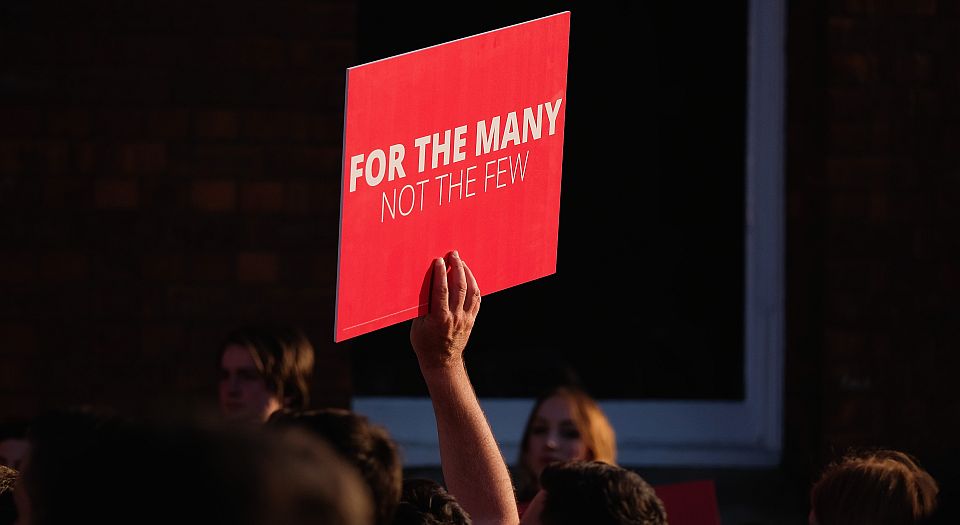

The conference revealed a reality gap in Labour’s plans for government.

Sounds of political revolution on the south coast this week, where shadow chancellor John McDonnell told the Labour Party conference in Brighton that the coming Jeremy Corbyn government ‘will be unlike anything seen before’. McDonnell assured ecstatic delegates that the party leadership is already ‘war planning’ to resist the capitalist counter-revolution that will follow newly radicalised Labour’s inevitable election victory.

Or perhaps it was more like a religious revival, to judge by the fervour of Corbyn’s chanting acolytes. There was even a reported proposal to have the leader deliver a sermon, sorry, speech floating on a platform in the sea; the plan for ‘JC’ to walk on water was apparently only cancelled on health-and-safety advice.

Is there any possibility that some might be getting slightly carried away? Paul Mason, the veteran Trotskyite who swapped the TV news for a role as professional Corbynista, declared the first six months of a Labour government will be ‘Stalingrad’, besieged by the ‘Establishment’. That momentous six-month Second World War battle between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany left an estimated 1,850,000 dead in house-to-house fighting. Perhaps Corbyn and McDonnell plan to nationalise the funeral industry to cope with nearly two million casualties on the streets of Britain.

Throughout the Labour conference, there appeared to be a reality gap between the fiery rhetoric and the rather anodyne actual proposals; between the political world as it is and as the Corbynistas imagine it to be.

That reality gap was revealed when Corbyn declared Labour the ‘government in waiting’, and instructed Tory prime minister Theresa May to ‘make way’ for Britain’s rightful rulers. His audience seemed convinced that Labour was more like a government in exile – the legitimate government, somehow deposed by a Tory coup. Media vox pops showed rank-and-file delegates and trade-union leaders assuring us that the Labour Party ‘really won’ June’s General Election, and would inevitably win the next one, too.

The inconvenient fact is that Labour did not ‘really’ win the election. Despite its much-improved showing, the extra 30 seats Labour won still left it a considerable 55 behind the Conservatives and 60-odd seats short of a majority. In other words, Labour would need to make double its ‘historic’ June gains again next time to form a majority government. Corbyn is certainly ahead of May’s floundering, fractious Tories in current opinion polls. But as Labour would normally be the first to tell us, you can’t trust polls…

Even if its cheerleaders are right, and Labour wins the next election, what sort of government would it be? There seems little reason to take the headline claims about the future at face value, any more than Labour’s rewriting of recent electoral history.

Did the conference show that Labour is really a radical force about to rock the status quo with an updated take on old-school socialism? Or is it more like a moderate new party of the metropolitan middle classes – ‘the sensibles’ as the Guardian’s arch Blairite Polly Toynbee approvingly described Labour this week?

In short, did Corbyn’s fighting Labour Party look like Mods or Rockers in Brighton?

- Hello John, goodbye TINA?

Shadow chancellor John McDonnell boasted of radical plans to transform the economy by re-nationalising the rail and energy industries and bringing £200 billion worth of Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contracts ‘back in-house’. Corbyn pledged to ‘end Tory austerity’ and Thatcherite ‘neoliberalism’ (whatever that might mean).

No doubt part of Corbyn’s appeal rests on this apparent willingness to break with the dour economic consensus of the age. Since the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher declared that There Is No Alternative, all political parties have bowed to the rule of TINA.

But are Jeremy and John really giving TINA notice to quit? Much of the economic radicalism at the conference seemed more rhetorical than real. Labour’s policies are still essentially based on the economics of book-keeping and the principle that, to quote that old Marxist, Monty Python, it’s accountancy that makes the world go round.

Take the pledge to bring PFIs ‘back in-house’. These huge government contracts with private companies, to build and service public assets such as hospitals and schools, were popularised as desperate measures of (not very) creative accounting by Labour chancellor Gordon Brown, to keep spending off the state’s books. PFIs are widely viewed as a rip-off that the public sector would love to see the back of. Yet a glance at the details behind the headlines suggests that McDonnell’s pledge is, in the words of one analyst, a ‘modest’ proposal for a lengthy review which ‘falls short of taking all or even any PFI contracts back’.

Elsewhere Labour’s apparently principled plans to expand spending have been described as ‘pure retail politics’, selectively aimed at securing key groups of voters such as students and pensioners. Meanwhile Labour’s election manifesto left billions of pounds of Tory welfare cuts intact. In different circumstances, if the Tories targeted tax cuts at their core constituents, Labour might surely feel justified in calling it bribery.

- State and revolution?

The big shift Labour promises is an expanded role for the state intervening in the market economy. Yet it is difficult to see what big difference its plans would make to a weak economy already heavily reliant on state support to keep going.

Even the supposedly strongest businesses in Britain – such as the pharmaceutical and armaments companies – make a lot of their money from state activities such as public procurement and official and unofficial subsidies. The formally privatised utilities that Labour says it will re-nationalise are already even more dependent on state subsidies and are highly regulated by state bodies. There seems little radical or transformative about moving the money from one column to another and bringing, say, the railways back under formal public ownership – the standard arrangement in European states of various political persuasions.

Labour’s pledge looks more like virtue signalling aimed at consolidating its support among public-sector workers than anything real to transform the low-productivity UK economy.

- Clause IV revival?

One thing that’s meant to demonstrate Labour’s new radicalism is the proposal to revive Clause IV of the party’s constitution. Clause IV’s commitment to wealth redistribution was long seen as the totemic symbol of Labour’s socialism. Tony Blair got a special party conference to replace it in 1995, as a sign of New Labour’s ascendancy. Now the Corbynistas ‘Party Democracy Review’ proposes reinstating Clause IV to show the party’s reborn radicalism.

Or so the headlines might have us believe. But look closer and the Clause IV story tells a slightly different tale.

The original Clause IV, adopted in 1918, committed the Labour Party ‘To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service’.

By contrast, Labour’s new draft Clause IV (as revealed in documents leaked to the Politico website) would timidly suggest that ‘Labour is a democratic socialist party [those words lifted straight from Blair’s version], working for a fairer, healthier and more equal society’.

A clause not exactly red in tooth and claw. It might be hard to imagine a more anodyne statement, one to which any political party could surely pay lip service once the token reference to socialism is removed. The drastically changed wording reflects historically changed times.

The original Clause IV was written by Sidney Webb in November 1917 – just after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. At a time of terrible world war and international political ferment, it was explicitly intended to offer the militant British working classes an alternative, peaceful road to socialism and turn them away from thoughts of revolution.

A century later, there is no sign of any militant working-class movement in Britain. Trade-union leaders may still strut about a Labour conference, but strikes are at an historic low and the public-sector unions which hold Labour’s purse strings have only managed to ‘win’ successive annual cuts in real pay for their members. The anodyne new Clause IV reflects those changed realities just as Blair’s did. Whatever combination of factors is behind Corbyn’s boost in popularity among middle-class voters, it is not any popular demand for a return to 1918-style class struggle and socialism. That is a reality that no amount of pro-Corbyn chanting and scarf-waving at a Labour conference can alter.

- Brexit – the real technocrats

A big part of Labour’s current appeal to young people is their self-image as a party of principle, set against the dull technocratic Tories. Yet when it comes to Brexit, Labour are not only acting as the real technocrats – they are even boasting about it.

Early media attention focused on the leadership’s apparent attempt to prevent conference voting on Brexit, and maintain the appearance of Labour unity. Yet there was plenty of talk about the EU in Brighton, most of it moving the party in one direction – away from Brexit and towards a form of Remain by another name, with the UK remaining part of the single market and subject to EU rules.

From the conference platform, Labour’s (anti-)Brexit spokesman Keir Starmer proudly announced that, unlike the Tory Brexit bunglers, Labour would have ‘no ideological red lines’ in EU talks, but would be ‘practical… pragmatic… the grown-ups in the room’. In other words, ‘We are the real non-political technocrats now!’.

The ‘ideological red line’ Labour seems happy to cross is the demand for democracy and sovereignty endorsed by 17.4million Leave voters – millions of them working-class Labour supporters. Labour’s anti-democratic turn, coming out as the main Remainer Party, reveals the ascendancy of the metropolitan middle classes within its policymaking circles.

Labour front bencher and close Corbyn ally Emily Thornberry told the conference that the Labour leader is a ‘person of principle… whose unshakeable values will carry him to Downing Street’. The one ‘principle’ and ‘unshakeable value’ that shone through everything in Brighton was the belief in state control and bureaucracy rather than freedom and popular democracy. That was evident in statements and debate about everything from banning Uber to controlling the press, culminating in the betrayal of Brexit.

‘Stalingrad’ seems unlikely to be repeated in 21st-century Britain. But the state-centred spirit of Stalinism still hangs over the Labour left.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His new book, Revolting! How the Establishment is Undermining Democracy – and What They’re Afraid of, is published by William Collins. Buy it here.

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.