Long-read

The SNP’s miserable autocracy

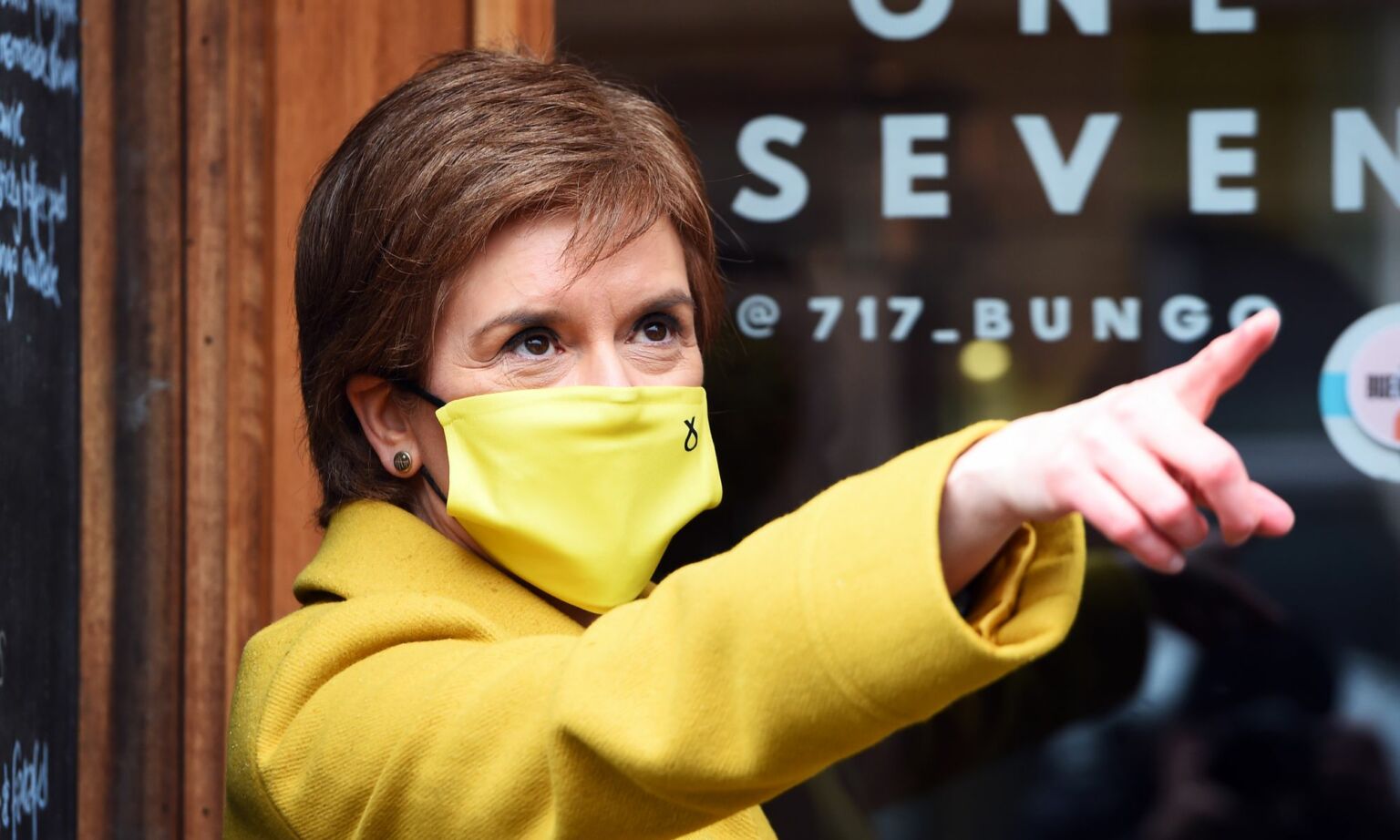

The Covid inquiry has exposed the authoritarian rot that was at the heart of Sturgeon’s Scotland.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Let’s get this straight: the Scottish government did not handle the pandemic well. And given the former first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, dominated the government to a control-freakish extent, it’s fair to say Sturgeon herself did not handle the pandemic well. She proudly imposed harsher restrictions for a longer period of time than in England or Wales. Yet not only did Scotland endure a similar Covid fatality rate to England, Scotland’s all-cause excess mortality was also greater than in any other nation of the UK.

So you would think that the mainstream media would want to see Sturgeon interrogated at Baroness Hallett’s UK Covid inquiry. After all, many pundits had salivated for days on end during former UK prime minister Boris Johnson’s appearances before the inquiry late last year. Surely they would want to see a figure who had overseen a response just as calamitous, if not more so, put to the sword by a leading KC?

Not a bit of it. After Sturgeon gave a tearful, defensive performance at the inquiry last week, the media response couldn’t have been more different to the one that greeted Johnson’s evisceration. There was no crowing over Sturgeon’s ‘exposure’, no accusations of ‘callousness’. Instead our media elites have virtually rallied to her side. Albeit with some minor criticisms attached.

‘We should feel sympathy for Nicola Sturgeon’, said the New Statesman. Others in the elite mainstream were similarly upset by her treatment at the hands of KC Jamie Dawson. Though critical of some aspects of Sturgeon’s rule, a Guardian piece lamented the harsh adversarial nature of the process, arguing that it ‘seemed less interested in learning lessons than in bringing politicians down’. Kirsten Campbell, the BBC Scotland political correspondent, practically went into bat for Sturgeon. Sturgeon’s display provides ‘real insight into the pressures she felt and still feels about the Covid pandemic’, Campbell said, no doubt wiping tears from her own eyes.

This is not entirely a surprise. Since Sturgeon replaced Alex Salmond as SNP leader in 2014, assumed the position of first minister and won a landslide victory north of the border at the 2015 General Election, she has enjoyed largely favourable and often stunningly uncritical coverage from the British media elites. Especially after Brexit in 2016, when her steadfast opposition to the electorate’s decision to leave the EU turned her into something of a pin-up for the Remainer establishment.

It seems that much of this residual support persists, even now. And it is obscuring a much-needed reckoning not just with Sturgeon and the SNP’s handling of the pandemic, but also with their wretched governance as a whole.

During its time in Scotland over the past three weeks, the Covid inquiry has further revealed the rotten nature of the Scottish state under Sturgeon and the SNP. They governed not as elected representatives, conscious of the needs and rights of Scottish citizens, but as a small clique of technocrats, utterly convinced that they knew what was best for people. They were aided and abetted in this by a civil service that was so pliant and submissive, it might as well have been integrated into the SNP.

The details revealed during the inquiry have been telling. We now know that key decisions were taken in so-called Gold Command meetings, featuring Sturgeon, deputy first minister John Swinney, national clinical director Jason Leitch and, at most, a few other select SNP ministers. These meetings took place behind so many sets of closed doors that even finance secretary Kate Forbes, the minister supposedly in charge of the purse strings, told the inquiry she was unaware of them.

It was this government-within-a-government that was making all the big calls, unencumbered by cabinet let alone parliamentary or public scrutiny. So it was Sturgeon and Swinney who unilaterally took the decision to close schools, despite being told by advisers it would do little to halt the spread of the virus, not to mention the deleterious impact that school closures would clearly have on a generation of young people. And it was Sturgeon alone who seemed to be deciding when to open and shut Scotland’s hospitality industry, despite the impact her whims were having on so many people’s livelihoods. In one WhatsApp message, she even admitted to ‘having a crisis of decision making’ over hospitality to her chief of staff.

The pandemic may have created an exceptional situation. But there was nothing particularly exceptional about Sturgeon’s technocratic absolutism. That was simply how she had become accustomed to ruling: with her clique from on high, surrounded by experts-cum-courtiers, civil service ‘yes’ men and friendly third-sector organisations. Indeed, the disastrous Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill, which would have effectively established gender self-ID in Scotland, was a product of precisely this high-handed technocratic process. As Helen Lewis has noted in the Atlantic, it was drafted by putative experts, pushed by Sturgeon from 2016 onwards, and backed by a pseudo civil society of NGOs and charities, dependent for their existence on government contracts. It met virtually no challenge or scrutiny from civil servants or an SNP-dominated parliament.

To make matters even less democratic, Sturgeon and the SNP have actively resisted scrutiny for much of their time in power. This was illustrated most clearly by the Scottish government’s handling of the harassment allegations made against former SNP leader Alex Salmond. Salmond has long argued that the accusations and investigations were politically motivated. While there is no evidence of any ‘conspiracy’ against him, the sordid affair at the very least revealed an institutional contempt for transparency and accountability.

First Salmond was investigated by the Scottish government. A 2019 judicial review ruled that this investigation was ‘unlawful’, ‘procedurally unfair’ and ‘tainted with apparent bias’ – the investigating officer had even had prior contact with Salmond’s accusers. Then Salmond was subjected to a criminal trial. In 2020, he was acquitted of 14 charges of sexual assault, including one attempted rape, involving 10 women. Some of the complainants, it was revealed, were SNP officials, others worked for the Scottish government.

Then, when a subsequent Holyrood inquiry was launched into the Salmond Affair, the government refused to hand over all the documentation related to the case and reveal what it knew. Most shocking of all, the Crown Office redacted Salmond’s evidence to the inquiry, and restricted what Sturgeon could be questioned about by MSPs. This would have been less suspicious if the Crown Office was not run by James Wolffe QC, the Lord Advocate, who also happened to be a serving member of Sturgeon’s cabinet. Wolffe denied any personal involvement, but the whiff remained. As then Scottish Labour leader Jackie Baillie put it at the time, ‘We are seeing that there is something rotten at the heart of the SNP, and it is poisoning our democratic institutions’.

That’s why the revelation during the Covid inquiry that Sturgeon and other senior members of the government had systematically deleted WhatsApp messages during the pandemic should shock no one. This was a ruling clique that has long been intent on avoiding accountability, on dodging scrutiny, on putting up barriers between its members and the public. In the words of an email sent by the SNP’s executive director general, Ken Thomson, during the pandemic, telling civil servants to delete their messages, ‘plausible deniability’ were Sturgeon’s government’s ‘middle names’.

Under the SNP and especially Sturgeon, power in Scotland was increasingly concentrated in the hands of a wilfully unaccountable, technocratic clique. Big political decisions weren’t subject to any real parliamentary or public debate. They were taken unilaterally, by Sturgeon and pals, informed by their chosen experts and justified as being in people’s best interests. Whether they liked it or not.

Inwardly, this form of government was narrow, absolutist, autocratic even. Outwardly, it resulted in an increasingly aggressive paternalism, an authoritarianism justified on the basis that, well, Nicola knows best.

This authoritarianism had been developing over more than a decade. From the moment the SNP became the largest party in Holyrood in 2007, it pursued New Labour-ish nanny statism with almost missionary-like zeal. It introduced new sin taxes on alcohol in 2010 in an attempt to force supposedly feckless Scottish citizens into changing their ways. It then set about trying to introduce minimum pricing for alcohol. Anything it seems to help dictate the consumption habits of Scots.

During the SNP’s early years in power, the health secretary was none other than Sturgeon herself. Her modus operandi was much the same then as it was when she became first minister. Backed by assorted third-sector lobbyists posing as experts, she ruled as if she knew what was best for people – indeed, as if ruling in this way was something to be proud of. ‘There is more work to be done and we will not shirk from leading the way in addressing this challenge’, she once boasted of the SNP’s attempts to price the ‘wrong’ people out of boozing.

From the moment she became first minister, Sturgeon’s aggressive paternalism became positively sinister. Take the Named Person scheme. Despite being introduced before her de facto coronation in 2014, Sturgeon soon became its principal champion. In short, this scheme promised to allot every child in Scotland a ‘named person’ to monitor and surveil their happiness and wellbeing – with or without parents’ consent. This named person was to compile a dossier to be shared with state authorities on the minutiae of every child’s life – from how their bedrooms are decorated to how much TV they’re allowed to watch. This was a spectacularly intrusive piece of legislation. It promised to introduce a Big Brother-style state power into the intimate lives of families across Scotland, undermining that most fundamental of all relationships – that between parents and children. It was struck down by the UK Supreme Court in 2019 for breaching the human right to a ‘family and private life’. But the SNP’s authoritarianism persisted.

Then came the Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021, which made it an imprisonable offence to behave in an ‘abusive’ manner ‘intended to stir up hatred’ against certain protected groups. Perhaps the most concerning aspect of this law is that it allows the police to investigate private conversations in the home. It is positively Stasi-like in its invasiveness. The only thing that has stopped it from doing any actual damage is that the authorities have held off from activating their new powers as they struggle to work out how to exercise them.

Given all this, the SNP’s response to the pandemic should have been no surprise. The state of emergency allowed the SNP leadership group to give free rein to its worst instincts. At every stage, Sturgeon, holed up with her Gold Command colleagues, eagerly introduced stricter rules that lasted much longer than they did in the rest of the UK. Scots had to wear mandatory face coverings on public transport and in most indoor settings for almost two years without respite. At certain points in the pandemic, they were limited to travelling within only a five-mile radius of their homes. Predictably, the Scottish government imposed ‘vaccine passports’ on far more social events in Scotland than No10 did south of the border.

The nanny state of the SNP’s early years became a thoroughly nasty state during the pandemic. Sturgeon and pals relished the opportunity to decide where people could go and who they could meet. This had terrible, tragic consequences. Many elderly people in care homes were effectively prevented from seeing their loved ones for the last time. Families were torn apart. And all this with much more zeal than was going on south of the border.

This approach to Covid was awful enough in itself. That it was likely driven in part by the SNP’s shameless political opportunism is reprehensible. Sturgeon effectively saw the pandemic as a chance to show that the Scottish government was ‘better’ than the UK government in Westminster. That she was superior to Boris Johnson. That Scotland should therefore be independent.

The Covid inquiry has certainly indicated as much. At a cabinet meeting in June 2020, with the pandemic still in full swing, Sturgeon and colleagues ‘agreed’ to re-start campaigning for independence and another referendum. The case for independence, read the minutes, should be updated ‘with the arguments reflecting the experience of the coronavirus crisis’.

At the inquiry, Sturgeon was forced to deny that she had exploited the pandemic for political gain. It was difficult to believe. She staged daily televised press conferences long after Johnson and Co had stopped theirs. The main purpose of these seemed to be to project Sturgeon as a more assured, more competent leader than Johnson. They were designed to show that Scotland was having a ‘better’ pandemic than England. Sturgeon even boasted in one appearance that Covid was five times less prevalent in Scotland than in England. In some of the few WhatsApp messages shared with the inquiry, Sturgeon complained to her chief aide, Liz Lloyd, that her government wasn’t getting ‘nearly enough credit for how much better than [the government in Westminster] we are’. As if that was the point.

Such was her drive to exploit the pandemic, to showcase the supposed superiority of Scotland’s Covid tyranny, that Sturgeon began flirting with the so-called Zero Covid approach during 2020 and early 2021. With Edinburgh academic Devi Sridhar at her back, Sturgeon told Holyrood in March 2021 that the government’s ‘objective has to be to eliminate’ Covid entirely. Scotland’s chief medical officer revealed to the inquiry that he had repeatedly told Sturgeon that elimination was impossible in Scotland. That the severe Zero Covid lockdowns in New Zealand and Australia were only possible by geography and circumstances that Scotland lacked.

But that didn’t matter. She wasn’t promoting Zero Covid because it was likely to work. She was floating it in order to grab the moral high ground. To appear to be more resolute and caring than the politicians in England who were willing to talk about easing restrictions and living with Covid. She wanted to look as if she was the only British politician willing to ‘put people’s lives first’.

Sturgeon effectively turned pandemic management into a PR exercise. A chance to signal hers and Scotland’s virtue. A chance to show that the SNP is a cut above the callous Tories down south. A chance once again to dress up the Scottish government’s authoritarianism as something noble.

This cynical exploitation of the pandemic did not come out of nowhere. It was entirely in keeping with Sturgeon’s approach to Scottish independence. In her hands, this was never a project of national self-determination, as the SNP’s eagerness to rejoin the EU attests. No, it was an elaborate attempt to show that Scotland was morally superior to the Tory-voting throng down south.

In Scotland, Sturgeon consistently marshalled an elitist, authoritarian disdain for the ‘masses’, rife throughout the SNP-dominated institutions of public and political life, and projected it ‘down south’, on to the English. This is how she conceives and understands independence, as a chance to liberate Scotland from supposedly ‘backward’ values and political culture of England.

This was all too visible during Covid, as she eagerly portrayed herself and her nation as more caring than her English counterparts. And it was visible too in the aftermath of Brexit, when she publicly rehearsed numerous Guardianista talking points about how Brexit has revived racism and licensed xenophobia in England. And while she was conjuring up England as a regressive, semi-fascist dystopia, she was presenting Scotland as a ‘progressive, inclusive, outward-looking’ woke-topia, as the SNP’s 2021 manifesto had it.

Ironically, it was this protracted culture war that was to prove Sturgeon’s undoing. The SNP had been championing gender self-ID, in the shape of its Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill, since 2016. Sturgeon no doubt saw it as the ‘caring’, virtuous position – as yet another means to demonstrate just how ‘forward-thinking’ Scotland is. Her and the SNP’s support for the bill only intensified from the late 2010s onwards, as opposition grew to similar proposed legislation in England, before Boris Johnson eventually ditched the proposals in 2020.

The problem, however, was that gender self-ID was neither virtuous nor in line with the views of the Scottish people. Quite the opposite. By the early 2020s, prominent figures and politicians in Scotland, from JK Rowling to SNP MP Joanna Cherry, were drawing attention to the danger of gender self-ID to women’s rights. Worse still for Sturgeon, the more the Scottish people were learning about the impact of gender self-ID, the more they didn’t like it. Yet Sturgeon and her clique of technocrats, backed up by trans-activist NGOs and charities, were convinced that they were right. And so they doubled down.

In January last year, the domestic tensions around the gender bill were brought to a head by the Scottish prison system’s decision to put male rapist ‘Isla Bryson’, now self-identifying as a woman, into a women’s prison. The Isla Bryson scandal provoked huge public outrage in Scotland, and exposed the cruel absurdity of gender self-ID.

But it did something else, too. It finally exposed the rot at the heart of the Scottish government to the public. A small group of technocrats had been allowed to make bad decisions unencumbered by scrutiny, challenge or simple common sense for far too long. They were too caught up in their anti-English politicking to see the folly of their own positions. Suddenly, Sturgeon was being brought down by the very culture war that had once lifted her up. Little more than a month after the Isla Bryson affair, Nicola Sturgeon resigned.

Since the gender self-ID fiasco and Sturgeon’s subsequent, sudden resignation, her halo has well and truly slipped. In March last year, her husband, Peter Murrell, was forced to step down from his role as the SNP’s chief executive, after he was found to have inflated the party’s membership figures. A month later, Murrell was arrested by the Scottish police as part of their ongoing investigation into allegations of financial misconduct within the SNP. Worse was to follow for Sturgeon, when she too was arrested and questioned in June last year as part of the same investigation. (Due to Scotland’s draconian reporting restrictions, there’s not much more we can say about those arrests.)

Now the Covid inquiry has shed further light into the murky administration of Scotland under Sturgeon and the SNP. It is about time. For too long, Sturgeon and the SNP have been allowed to get away with governing Scotland appallingly. Over the course of a decade and more, they have acted like a one-party state, with power concentrated in a small group of arrogant technocratic politicians and civil servants. They have waged war on the everyday freedoms of Scottish people, backed up by the propaganda of the state-funded NGO-cracy.

At the same time, they have presided over the decline of Scotland’s public realm. They have overseen the precipitous decline of Scotland’s education system, with it reaching a record low in the international PISA rankings in 2019. They have run down the Scottish NHS, with patients’ waiting times now comfortably exceeding those even for patients in England. They have allowed Scotland to continue to record the highest rate of drug deaths in Europe. They also handled the pandemic terribly, imposing inhuman restrictions on citizens for little to no gain.

This ought to shame those among our political and media elites who still refuse to scrutinise the reality of the SNP’s wretched rule. They see Sturgeon tear up during the Covid inquiry and are moved to defend her. All because they see her as being on their side of the culture war. On trans, on Brexit, indeed, in their disdain for the English working classes, Sturgeon sings from the same hymn sheet. That’s why, in the words of the Guardian’s Owen Jones, they are convinced that ‘history will be kind to her’.

But the more that comes to light, the less plausible that sounds. A reckoning with the SNP is long overdue.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.