What Macron and Le Pen have in common

Neither candidate has a compelling vision to overcome France’s deep divides.

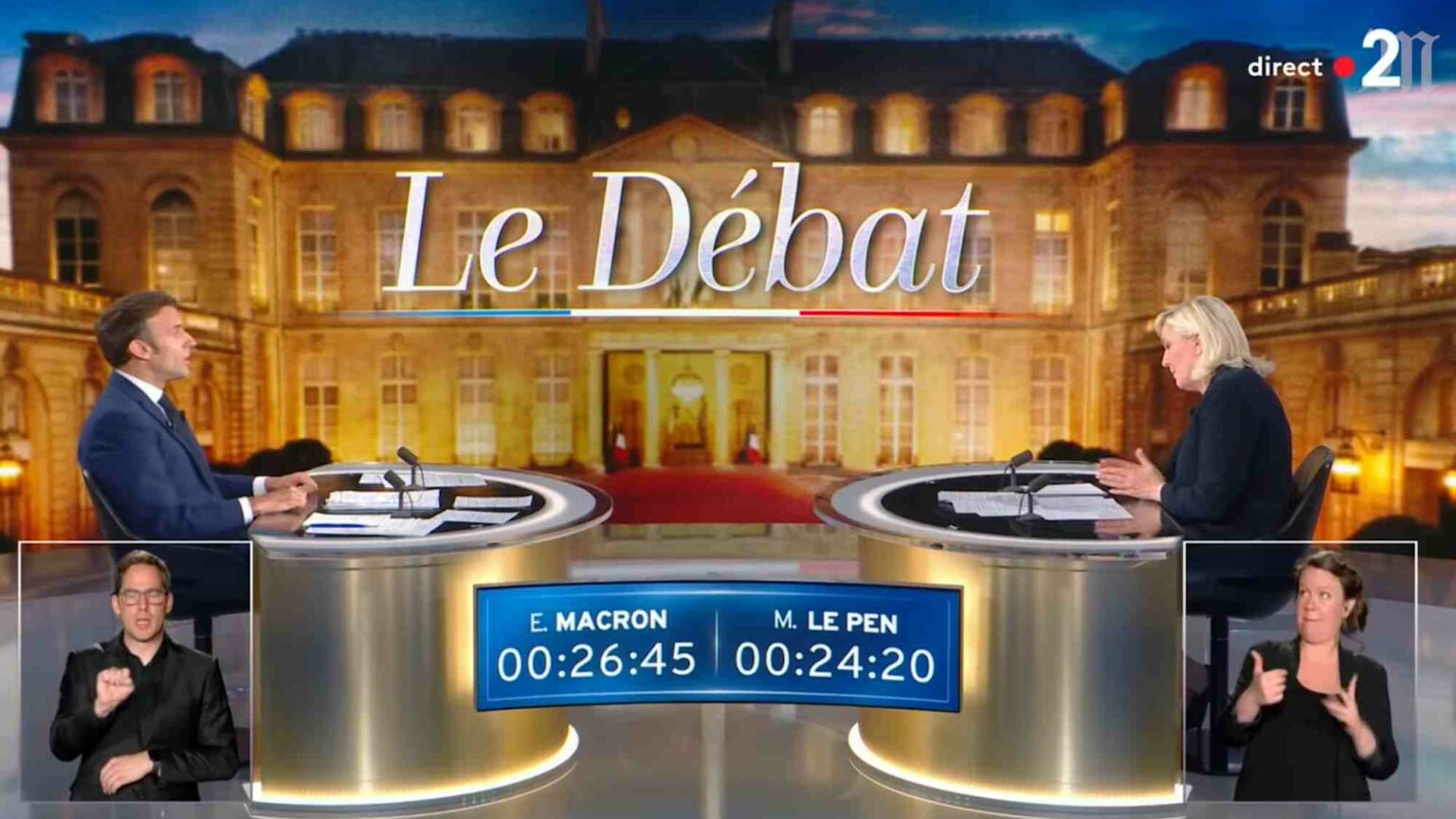

Last night, ahead of Sunday’s second round of the French presidential elections, French voters were treated to a marathon, two-and-a-half-hour debate between incumbent president Emmanuel Macron and hard-right challenger Marine Le Pen. The gloves were off. Macron accused his rival of being on Vladimir Putin’s payroll and of potentially stoking ‘civil war’. In turn, Le Pen accused Macron of causing ‘unprecedented suffering’ and slammed his proposed pension reforms as an ‘unbearable injustice’.

The coming Macron / Le Pen face-off has variously been portrayed as an existential battle for France’s future. In Macron’s own words last night, it will be a ‘referendum’ – ‘for or against the EU… for or against the ecological transition… for or against secularism… a referendum for or against what we are’. But while the stakes are certainly very high for France and Europe in this election, a number of commonalities between the two candidates became clearer during last night’s debate.

On the economy, Le Pen pressed home the cost-of-living crisis. But aside from offering various tax cuts to lessen the immediate squeeze, and criticising some of Macron’s reforms, she is not promising a great deal of structural change.

The overriding vision she presented last night was one of protectionism – France first. She railed against imports of ‘Brazilian chickens’ and ‘Canadian beef’ flooding French markets and placing French farmers at risk.

But Macron is no free-trade enthusiast, either. It is just that he prefers his protectionism at the EU level. His vision for the EU is usually summed up with the buzzword ‘strategic autonomy’, which is really just a polite, technocratic way of arguing for regional protectionism. He boasted in the debate about his blocking of an EU trade deal with Mercosur, the South American trade bloc. Fellow European leaders have also long viewed him as an obstacle to the EU signing trade deals with the outside world. Both Macron and Le Pen would continue the existing global trend away from globalisation and towards protectionism.

Clashes over the climate revealed a similar dynamic. Macron accused Le Pen of being a climate sceptic, all because she has called for a slowing of the green transition and a French exit from the European Green Deal, which since 2020 has committed EU nations to reaching Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050. Macron has tried to present himself as the green candidate in these elections and has made a flurry of eco announcements in recent weeks.

But many of Le Pen’s attacks on Macron also had a distinctly green hue. She called him a climate hypocrite. She accused his preferred economic model of ‘killing the planet’. She blamed greenhouse-gas emissions on international trade – ‘producing 10,000km away to consume 10,000km further’ – which she vowed to replace with a more eco-friendly ‘localism’. This is nothing new for Le Pen, nor for the European right more broadly. In 2019, she declared environmentalism to be the ‘natural child of patriotism’. In this sense, Macron and Le Pen are essentially offering two different versions of green austerity – of a future either constrained by undemocratic, supranational CO2 targets, or limited to mainly ‘local’ consumption and production. Each is miserable in its own way.

Perhaps the greatest commonality between the two candidates is that neither has a compelling, positive vision for France. They are both products of the French establishment’s political exhaustion. After all, they are on the debate stage, for the second election running, because support for the old parties of the centre-left and centre-right collapsed at the last election.

Both candidates are hoping that a substantial number of voters will hold their noses and vote for them, due to their disdain for the other one. Macron is hoping to assemble a ‘republican front’ to keep the extremist out of the Élysée Palace. Meanwhile, Le Pen is trying to build an anti-Macron coalition. For most voters, the question on the ballot paper on Sunday will be ‘who do you least want to win?’.

Whoever emerges victorious, neither Macron nor Le Pen is going to resolve the division and disillusionment that is currently afflicting France.

Fraser Myers is deputy editor at spiked and host of the spiked podcast. Follow him on Twitter: @FraserMyers.

Picture by: YouTube.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.