Why talented artists are leaving fine art behind

The world of fine art has become drab and woke. So artists are pursuing their passions elsewhere.

Imagine that you are young and you have a passion for a sport, say, javelin throwing. You watch videos of javelin competitions. You buy your own javelin and throw it in a nearby field for hours every day. You then join a javelin club with expectations of becoming a professional sportsman. But the club is not what you expect.

Club members don’t seem to practice javelin throwing much. And they not only admit members who don’t throw javelins, but they also actively dislike javelins and javelin-throwers. They call javelin-throwers supporters of racial oppression and reactionary politics. You stop going to the club, regretting that you devoted so much energy to the pastime.

It sounds odd but that’s not far from the situation in fine art. If you love making skilful images of figures, objects and landscapes, it is highly likely that members of your profession will sneer at you – at worst, you will be accused of upholding exclusionary standards. Even art tutors struggle to teach the skills now because they themselves have not been taught them.

So when using skill to depict worlds in two dimensions in the field of fine art is deemed suspect, where do traditional art-makers go? The new book, Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration, which explores the diverse and dynamic art that comprises fantasy illustration, provides a hint. The exhibition of the same name at the Norman Rockwell Museum (Stockbridge, Massachusetts) links fantasy art to the high art of the past. It shows that we should see fantasy illustration as the evolution of a noble tradition rather than something puerile, childish or inconsequential.

In fine art today, there is a noticeable absence of human drama, storytelling and visual excitement – precisely the elements audiences (and many artists) are yearning for. Enchanted provides a compelling counterpoint.

Beginning in Babylon and Egypt, with carvings of mythical creatures, and sculptures, it moves through the history of fantastical high art, including masterpieces from the eras of the Renaissance (Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder); Romanticism (William Blake, Richard Dadd, John Martin); Pre-Raphaelites (John William Waterhouse); and the Victorian salon (William-Adolphe Bouguereau).

Bouguereau’s masterful Nymphs and Satyr (1873), combining verisimilitude, narrative and erotic titillation, is a high point. It features a reluctant satyr being teased and tempted by naked nymphs, who lead him to water – either to ‘dampen his ardour’ or even drown him.

But Nymphs and Satyr is also something of an endpoint. Towards the end of the 19th century a division opened between high and low art (or fine and popular art). Illustration ceased to be a common pursuit for the fine artist, and the skills of naturalism were no longer necessary in painting. It was during this period that fantasy was disparaged as an object for fine art.

Artists – such as Arthur Rackham, Maxfield Parrish, Howard Pyle, Walter Crane, Edmund Dulac, Harry Clarke and Morris Meredith Williams – who continued to pursue illustration became household names for their work on classic stories. And although Norman Rockwell rarely depicted the impossible or fantastic, Enchanted includes Mermaid, which features a fisherman carrying a mermaid in a basket; and Armor, which depicts a museum security guard surrounded by suits of armour.

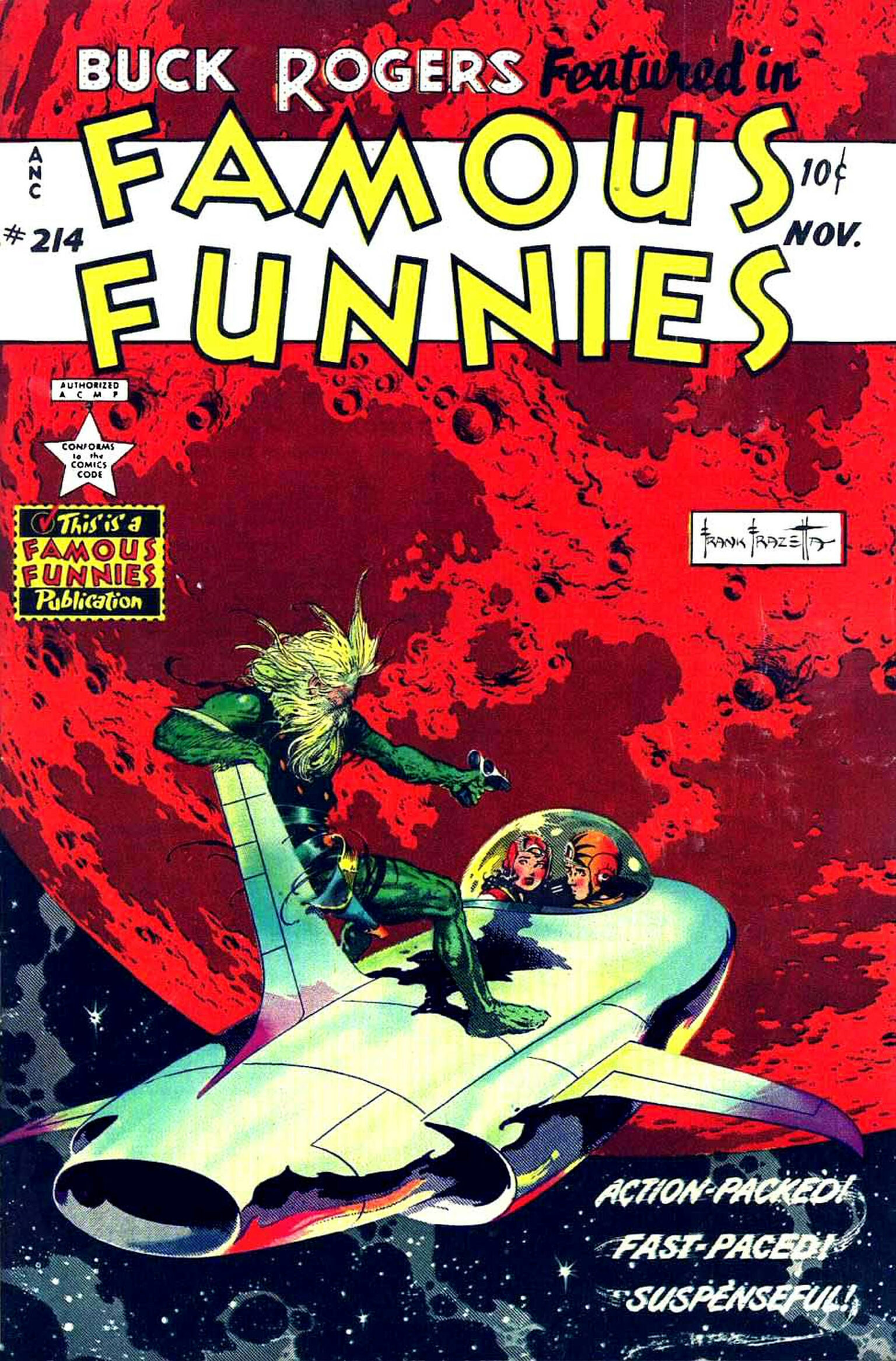

Many mid-20th-century pulp magazines had a roster of artists who made a living from illustrating covers. Pulp, sci-fi and crime magazines of the interwar era required a regular supply of art, not all of it accomplished. This evolved into comic-book art, some of which by Mike Mignola and Terry and Rachel Dodson is featured in Enchanted.

Indeed, comic books and graphic-novels (since the relative decline of journal and book illustration) have become the greatest repositories of narrative representational art today. The tanned muscle-bound barbarians and skimpily clad maidens of Frank Frazetta and Boris Vallejo became famous in the 1960s and 1970s and were staples of book covers, magazines and posters. The winning formula of attractive archetypes engaged in drama, conflict and rescue was appealing to those seeking escapism.

One contributor to Enchanted notes the snobbery towards fantasy illustration. ‘Dragons, sirens, larger-than-life heroes, black-hearted villains and supernatural happenings’, he writes, ‘were “kids’ stuff”, subjects to be ignored by anyone aspiring to create “high art”, (no matter that museums around the world showcase and celebrate works featuring such mythic characters and scenes)’. There is little doubting the skill and technique required for fantasy illustration. It often requires a high degree of verisimilitude because the characters, objects and places depicted are unfamiliar and the eye needs to be treated to persuasive and descriptive content. The requisite fidelity, research and diligence is often alien to contemporary fine artists, who consider themselves above such considerations.

Alongside videogame design, CGI, graphic novels and comic books, fantasy illustration is one of the refuges for artists who love describing figures, characters and dramatic action. It is a living tradition. Hence Enchanted includes many artists working today. Fantasy artists such as Iain McCaig (who made his name with the Fighting Fantasy series) have branched out. McCaig’s Star Wars painting enters the territory of movie poster or DVD box art. Eric Velhagen combines the heroism of Frazetta with the brushwork of an action painter, which gives his art ambiguity and energy. The sweeping vistas of Michael Whelan recall the expansiveness of John Martin or the Hudson River School of landscape painters.

Commercial and fantasy artists are just as resourceful as their fine-art cousins. In addition to being flexible about commissions, they sell directly to fans through internet sites, social media and conventions. Fantasy artists have found work producing concept art for videogames and films. McCaig, for instance, designed the characters Padmé Amidala and Darth Maul, for the Star Wars prequels.

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration sketches the evolution of fantasy art, the major figures and explains why we should pay more attention to this overlooked art form. It may be that the most talented artists in the world today are not in the fine arts and on the red carpet at biennales. They’re actually producing art for movies and games.

Alexander Adams is a writer and artist. His latest book is Iconoclasm, Identity Politics and the Erasure of History (Societas, 2020). His website is here.

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration, edited by Jesse Kowalski, is published by Abbeville Press/Norman Rockwell Museum. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: wikimedia commons.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.