How Britain became institutionally anti-racist

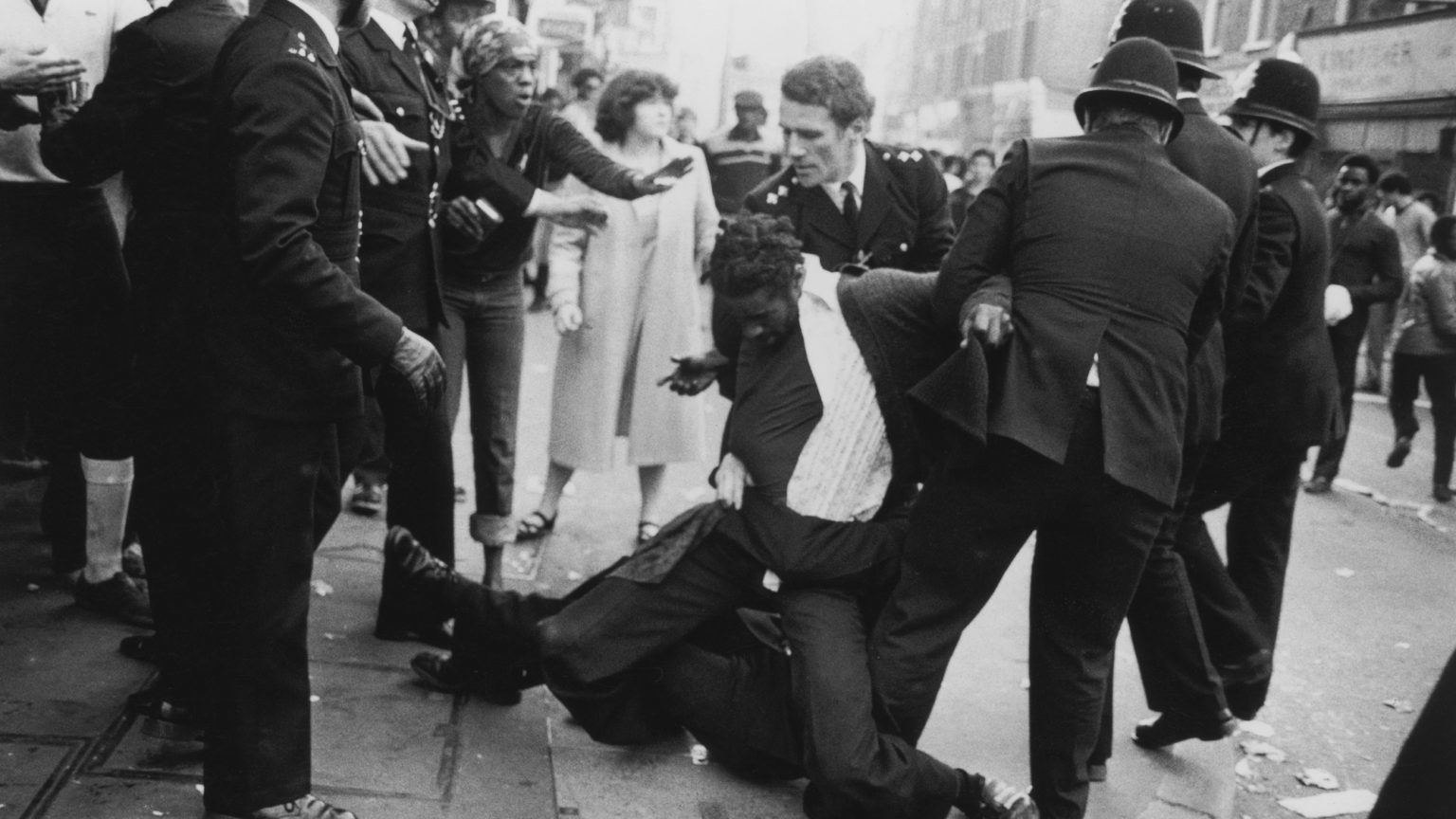

Since the 1981 Brixton riots, race relations have changed beyond recognition.

Forty years ago, riots in Brixton, south London, changed the face of race relations in Britain, but few seem to want to believe it.

The police had clashed with the growing West Indian community before April 1981, notably at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1977, and at a protest march a month before, over the New Cross fire. The Brixton riot was provoked by a heavy-handed police operation called ‘Swamp ’81’. Officers flooded the area to stop and search young black men. Over the weekend of 10 to 12 April, clashes turned to rioting and the police lost control of Brixton.

The conflict did not come from nowhere. Britain was in a miserable and paranoid mood. There was economic instability and recession, and its political leaders promoted an aggressive patriotism to compensate. Before she became prime minister, Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher made a sop to the far-right National Front, saying that ‘people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture’ – which was where the police operation got its name.

‘In the Jamaicans you have people who are constitutionally disorderly’, said Met commissioner Kenneth Newman: ‘It’s simply in their make-up’. Newman was characteristic of the cadre of senior officers in the 1980s, like James Anderton in Manchester and Kenneth Oxford in Liverpool, who looked on young West Indian men as a public-order problem and treated them accordingly.

Forty years on, Britain is a greatly changed place – not least because of the Brixton riots, and the reaction to them. The initial official reaction to the disturbances was to insist that there was no great issue. Lord Scarman’s report only begrudgingly admitted that there were shortcomings in the way the police reacted; it dismissed a general problem of racism. Thatcher’s government reacted defensively to guarded criticisms coming from the Commission for Race Equality (CRE) and cut its funding. Slowly, though, things were changing.

Businesses started to adopt equal-opportunities policies promising to act against discrimination at work. This was led first by local authorities, followed by banks, Ford UK and even the civil service. By 2004, three quarters of all workplaces had them.

Reform of the police – and indeed of all public institutions – was given a boost by Sir William Macpherson’s inquiry into the racially motivated murder of Stephen Lawrence in Eltham, and the police’s failure properly to investigate it. Macpherson concluded that the force failed because of ‘institutional racism’. Indeed, the report went further, saying that ‘if racism is to be eradicated, there must be specific and coordinated action… not just in the police services, but in all organisations’.

The reform of race relations in Britain has been remarkable. Where the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1976 were initially seen as relatively toothless, the promotion of equal opportunities at work by the CRE, created by the latter act, would later prove groundbreaking. The 2000 Race Relations Act that followed the Macpherson Report imposed a statutory and ongoing duty on 40,000 public bodies to promote racial equality. The criminal law changed, too. In 1989, the police began monitoring racially motivated attacks, and in 1998 these were criminalised.

This is the context to the recent controversy over the report of Tony Sewell’s Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities. The main thrust of the report, and the one that drew the most criticism, was the argument that, while there is racial discrimination, it is wrong to conclude that Britain is ‘institutionally racist’.

Many protested that Sewell was trying to overturn the conclusions of the Macpherson report (and the subsequent report by David Lammy into the criminal-justice system). It would be more accurate to say that Sewell is asking us to recognise that the Macpherson report has been acted on.

Sewell is right. If you were to look at legislation and workplace policies, or at public attitudes and statements, you would conclude that Britain is institutionally anti-racist. On some levels, as Sewell’s report shows, the consequences of the change in British policy and attitudes have been very positive. Before the economic damage done by the Covid lockdown, the evidence showed that racial disparities in employment and incomes had markedly improved. And at schools and universities, Britain’s ethnic minorities have done much better in recent years than in the 1980s and 90s.

On the other hand, as many of Sewell’s critics have pointed out, unequal outcomes in health (evidenced in the coronavirus figures), in school exclusions and stop-and-search detentions, and in bigotry against Britain’s Muslim population, all suggest that problems persist.

Top-down anti-racist legislation is symptomatic of a sea change in public attitudes, that sees race discrimination as fundamentally wrong. In itself, though, it has not always led to openness and tolerance. Race relations, particularly in the workplace, are sometimes marred by distrust that helps employers more than it does employees. What is hard to dismiss, though, is that Britain today is a very different place than it was in 1981.

James Heartfield is author of The Equal Opportunities Revolution, published by Repeater.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.