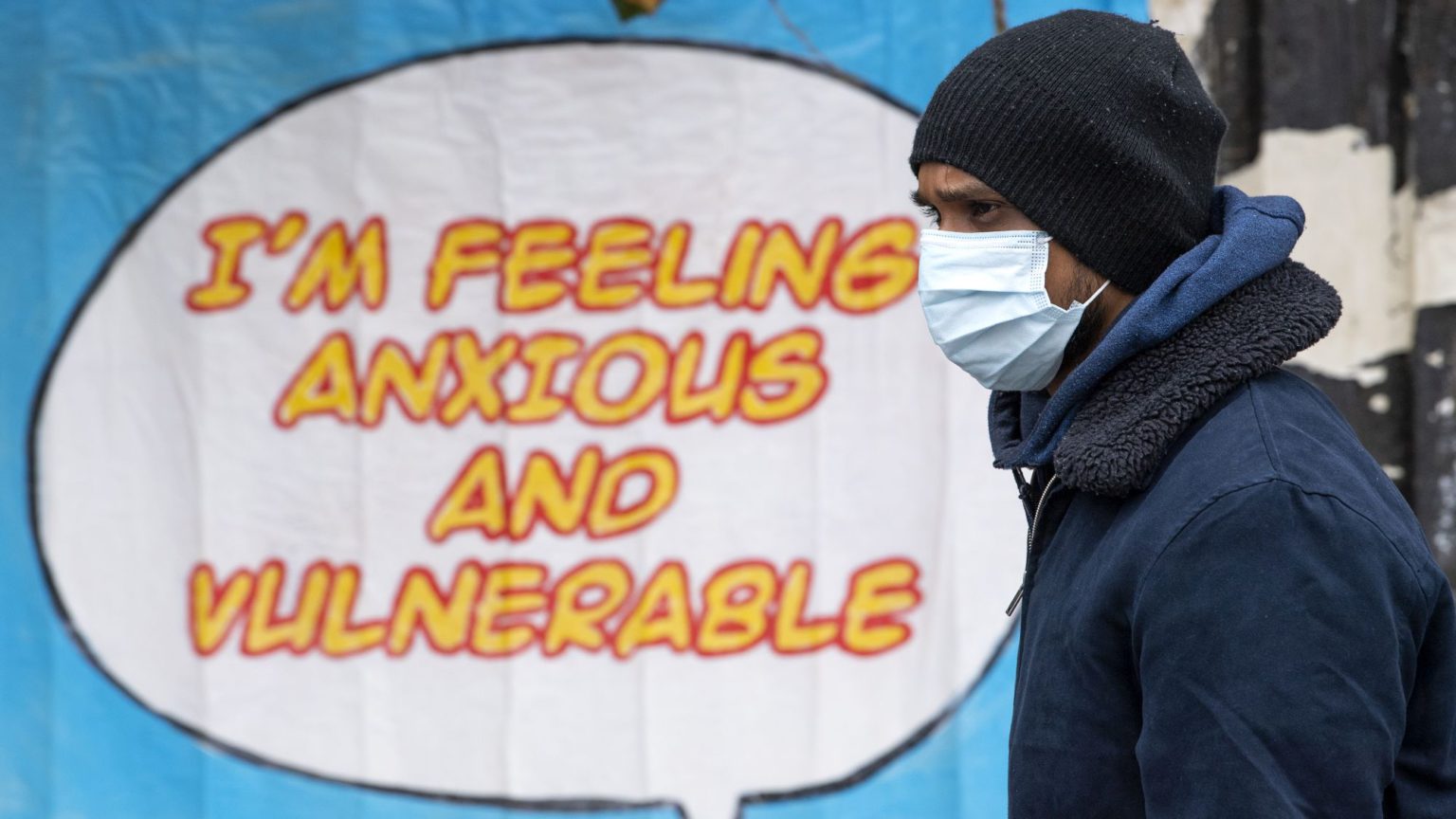

Are we all vulnerable now?

Our exaggerated sense of vulnerability has driven us to catastrophe.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

At a time when some have been self-isolating or shielding because they are ‘very vulnerable’ or ‘clinically extremely vulnerable’ to Covid-19, just how vulnerable are we really? I ask the question not out of a perverse disregard for those affected, but because vulnerable is a term that gets thrown about a lot these days.

While it might be understandable, with a nation confined to their homes, that concerns would be raised about our mental health, widening girths, alcohol consumption, online-gambling addictions, our children’s welfare and rising levels of domestic abuse, it doesn’t stop there. For instance, in recent weeks some less-than-sympathetic characters – including ex-member of the royal family Meghan Markle, and ex-member of ISIS, Shamima Begum – have been described as ‘vulnerable’.

There is no doubt, as commentators have pointed out, that it tends to be ‘the vulnerable’ who are suffering the most during the pandemic – be it rough sleepers, people with disabilities, children with special educational needs, or isolated older people. Children’s charity Coram is the latest to report concerns over an unprecedented rise in calls to its helpline and visits to its website concerning domestic violence. Nevertheless – even allowing for these quite predictable outcomes of keeping people, already suffering serious problems, under house arrest – the relentless catastrophising and intensification of the often lobby-driven and fashionable anxieties of the pre-pandemic period have been unhelpful.

Some appear to have courted the sympathy that can attend high-profile claims to vulnerability. Sadiq Khan, mayor of London, admitted in an interview with The Sunday Times to struggling with his mental health during lockdown. Weeks-long confinement in his south London home had left him ‘feeling a bit down’. Khan confessed to feeling ‘fragile’ and admitted that at times he was not able to provide ‘proper leadership’ – quite an admission, you might think, given the status and profile of his job, particularly when there is a pandemic on. Yet when asked about these revelations at City Hall by a sympathetic member of the London Assembly, the mayor accused the questioner of contributing to the ‘stigma about mental health’ experienced by him and other vulnerable Londoners.

Of course, some people are genuinely vulnerable – a qualifier I wouldn’t need to use if it wasn’t for the promiscuous use of the word. The abused (or should I say the seriously abused?) and the suicidal come to mind. The Khan case is striking because, as someone working in social care, I have yet to meet anybody who self-identifies as vulnerable. Indeed, the bolshiest of individuals and the least likely to accept this meek and passive status are the ones typically assigned to so-called vulnerable groups. They are far more likely to exhibit a real determination to get on with their lives: whether they are kids leaving the care system or old people stubbornly hanging on to their independence.

While enlightened policymakers and social workers have sought to enable people with care needs to overcome their limitations, plan their own care and live the lives they want to lead, there is still an underlying paternalism, dehumanising managerialism and suffocating risk-aversion that tends to hobble attempts to transform social services for the better. As recent events confirm, while these problems are top-down in origin and rampant in the institutions of the state, they are now impacting on wider society.

Charities, campaigners and, perhaps most notably, the Labour Party (not least its most high-profile members) are adept at hiding behind this imaginary constituency of ‘the vulnerable’. They ventriloquise and claim to speak on behalf of a group that, unlike the annoyingly pro-Brexit and increasingly pro-Tory working classes, is defined by its experience of weakness and victimhood.

One might well ask if there is anybody left who is not vulnerable, or who does not belong to a vulnerable group. The indiscriminate use of the word is an expression of how exaggerated people’s sense of both their own and other people’s fragility has become. The calls from teachers’ unions for mandatory masks for children are just the latest expression of a profoundly damaging trend. As much as it triggered the lockdown, today’s acute sense of fear and paralysis is the consequence not so much of a particularly nasty virus afflicting relatively few, but of a profound cultural anxiety that is decades old.

However deep-rooted our sense of dread, we are evidently less vulnerable to the virus than we are to state-sponsored neglect. By myopically focusing on the threat to the NHS, and neglecting everything else – from people’s jobs to the mortal threat Covid posed to people in care homes – we have been made vulnerable to potentially far greater calamities. It is now clear – as some were shamed for saying from the start – that while the virus was a serious public-health problem, the wholesale locking down of society and the economy could be even more catastrophic.

A government report published in April – but only making headlines recently when the chief scientific adviser Patrick Vallance referred to it at the Science and Technology Select Committee – estimates that 200,000 people could die within a year as a consequence of the lockdown: both as a consequence of delays in the provision of healthcare and from the impact of the recession it has triggered. That’s four times the current estimated mortality from Covid.

There has been an alarming readiness to accept this crippling safety-first absolutism, which is so very much at odds with the everyday risks that – at least until recently – we implicitly accepted as part of our everyday lives. We have become complicit in our own enfeebling. We need to stand up to the indefinite locking-down of society, the economy and our freedom, and live as we choose.

Dave Clements is a writer and policy adviser working in local government. He also chairs the Academy of Ideas Social Policy Forum. Follow him on Twitter: @daveclementsltd

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.