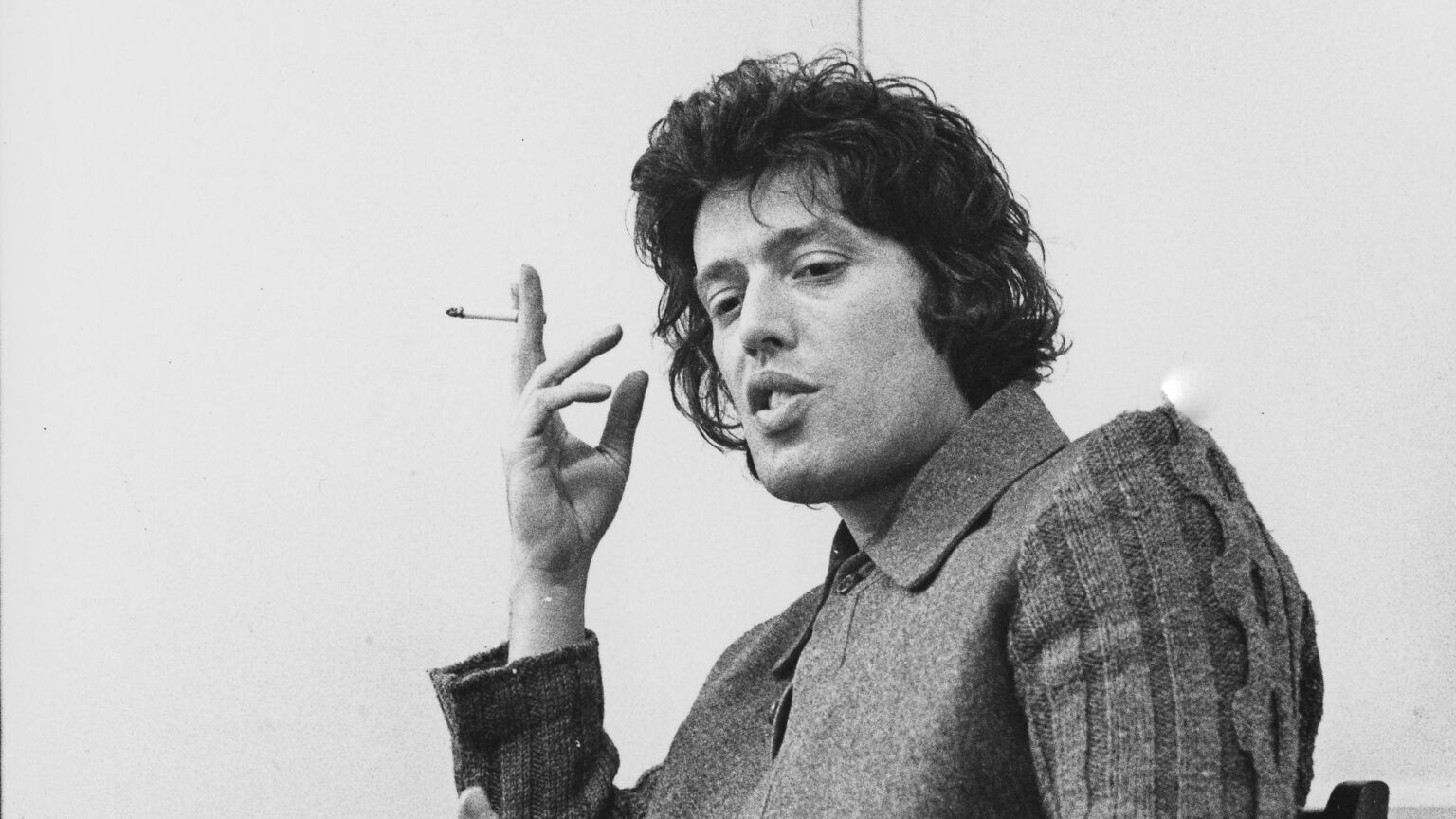

The magical genius of Tom Stoppard

The playwright has left us with some of the greatest plays – and gags – in the English language.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The death of Sir Tom Stoppard at 88 has, by universal consensus, deprived us of Britain’s greatest living dramatist and, some would say, writer. He was one of the most invigorating, singular and somehow slightly magical personalities to grace public life in the past 60 years.

Along with the silence and second-hand clothes that, as his Guildenstern reminds Rosencrantz, ‘death is’, Sir Tom has left us a shelf of pretty much unequalled intellectual chewiness. As many as 50 plays, each one an intricate dramatic structure, wriggling with ideas and verbal pyrotechnics. It is a bequest beyond price.

So to observe that, had Sir Tom only knuckled down, learned the rule of three and clocked up the stage time, he could have made a decent fist of stand-up comedy, might strike some as impudent. Still, I make no apologies.

If you want to read a conventional tribute from someone who worked with him in theatreland – co-writers, directors and actors – well, there are plenty of such tributes already out there. But stand-up comedy is what I do, and I think I recognised – in some intangible sense – a fellow traveller in Sir Tom.

It has been commonplace for decades now to insist that any comedian or sitcom writer should also be acknowledged as having slipped some trenchant social critique into their work. I think the single piece I’m most proud of for spiked might be my obituary for Eric Chappell, creator of Rigsby and Rising Damp – ‘Dostoevsky, backwards and in heels’. So, now that Sir Tom has shuffled off this mortal coil (to quote the work on whose wings he first swooped in), it feels only fair to note that whatever else he achieved, he was a gag writer of the first order.

Some of his plays are funny from beginning to end. The Real Inspector Hound snaps at the heels of Michael Frayn’s Noises Off as the most deliriously funny farce about farce of the last century. Any chance you get to see it, take it. There are usually a couple of seats free up front.

Even in a more ambitious play like Arcadia, where vastly more is in the mix than wordplay and innuendo, he finds time for an exchange like this:

Chater: (on learning that Septimus has been found in ‘carnal embrace’ with his wife) ‘You damned lecher… I demand satisfaction!’

Septimus: ‘Mrs Chater demanded satisfaction and now you are demanding satisfaction. I cannot spend my time day and night satisfying the demands of the Chater family…’

I love that, not least because it feels familiar, somehow. Nobody demands satisfaction nowadays (more’s the pity – I am sure that recourse to duelling would vastly improve standards of behaviour on public transport, for instance). But there is something about that exchange that sounds like a really good heckle put-down, perhaps to a man on the front row who thinks you have been rude to his wife. Chris Rock, take note.

But Stoppard also had a knack that I think many comedians vaguely aspire to but very few achieve – namely, of making audiences want to be smart enough to get the joke. Of convincing them that they needed to keep up. Not in the infamous way that audiences laugh at Shakespeare – to demonstrate that they are terribly clever. But genuinely, with delight, because for one brief moment they feel that they have kept up, and earned their prize.

For those of us who usually have to work material up in front of a crowd which always seems to be too drunk or not quite drunk enough, it is mortifying to see the enthusiasm with which a theatre audience grants playwrights the license to be funny about chaos theory and the second law of thermodynamics. But that is because the hard work of rehearsal and rewriting has been done far away from paying eyes – a part of the theatrical process Stoppard brought to life so brilliantly in Shakespeare in Love.

I realise it probably says more about me than the facts as they stand, but I recognise echoes and fellow feeling in much of Sir Tom’s life. The main difference, of course, being the success in execution. Indulge me…

Tom and I both find hermits funny, and wrote jokes about them. Tom and I both referenced Joyce’s Ulysses in our work, without having actually read it (though I at least admit as much – Tom did eventually read it. In a week). Tom and I both fancied Felicity Kendal. Again, execution is key.

There’s more. Tom and I both learned, in our fifties, that we were much more significantly Jewish than we had thought – though in his case, considerably more tragically. I was the son of donor conception, using sperm from a Jewish donor. This was a shock, and needed adjustment, but was not painful, exactly. Tom learned that all his grandparents – unbeknownst to him until his late middle age – had perished in the Holocaust.

And we both ploughed these revelations back into our work. In my show, Work of the Devil. Tom, obliquely, in his last great work, Leopoldstadt, which premiered – a few months after mine – just before lockdown, in February 2020. It would have been interesting to see how the rivalry might have played out, had not Covid intervened.

And – just to ease the bathos which you are now feeling – both of us were painfully aware that we held someone in very high esteem, whose accomplishments were vastly higher than our own and whose conversation, were we to meet, would no doubt swiftly reveal them to be breathing different air entirely. But whom we secretly nevertheless hoped might one day be aware of the tribute.

According to Hermione Lee’s 2020 biography, Sir Tom’s pedestalled hero was the physicist Richard Feynman. ‘I don’t think I’ve ever read an obituary which caused me such a stab of grief’, he wrote, ‘as I felt on reading of the death of an American physicist whom I had never met and whose work was way out of the reach of my understanding’. It was, he said, because he had wanted to send him a tribute and would now not be able to.

I don’t want to overdo it. While ‘met’ would be stretching it, I did at least make brief eye contact with my hero, Stoppard. He was stumping, more Pooh-like than the Great God Pan of Rock’n’Roll, in a long coat and a perfect scarf, across the badly broken ground of a literary festival on the Solent in about 2016.

I didn’t dare to approach him, but he glanced up and I managed to send him a hastily assembled smile which I hoped encompassed some of the gratitude and respect which he was owed. I offer this now, in the same spirit, and inadequate execution as ever.

Heigh ho. Sir Tom made it to 88 – exactly the same estimable age as the great Eric Chappell. Michael Frayn, another of the select few that are not afraid of ideas, is 92. After him? What can I say. I will do my best.

Simon Evans is a spiked columnist and stand-up comedian. Tickets for his tour, Have We Met?, are on sale here.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.