The tax-cut delusion

Tinkering with tax rates won’t revive our stagnant economy.

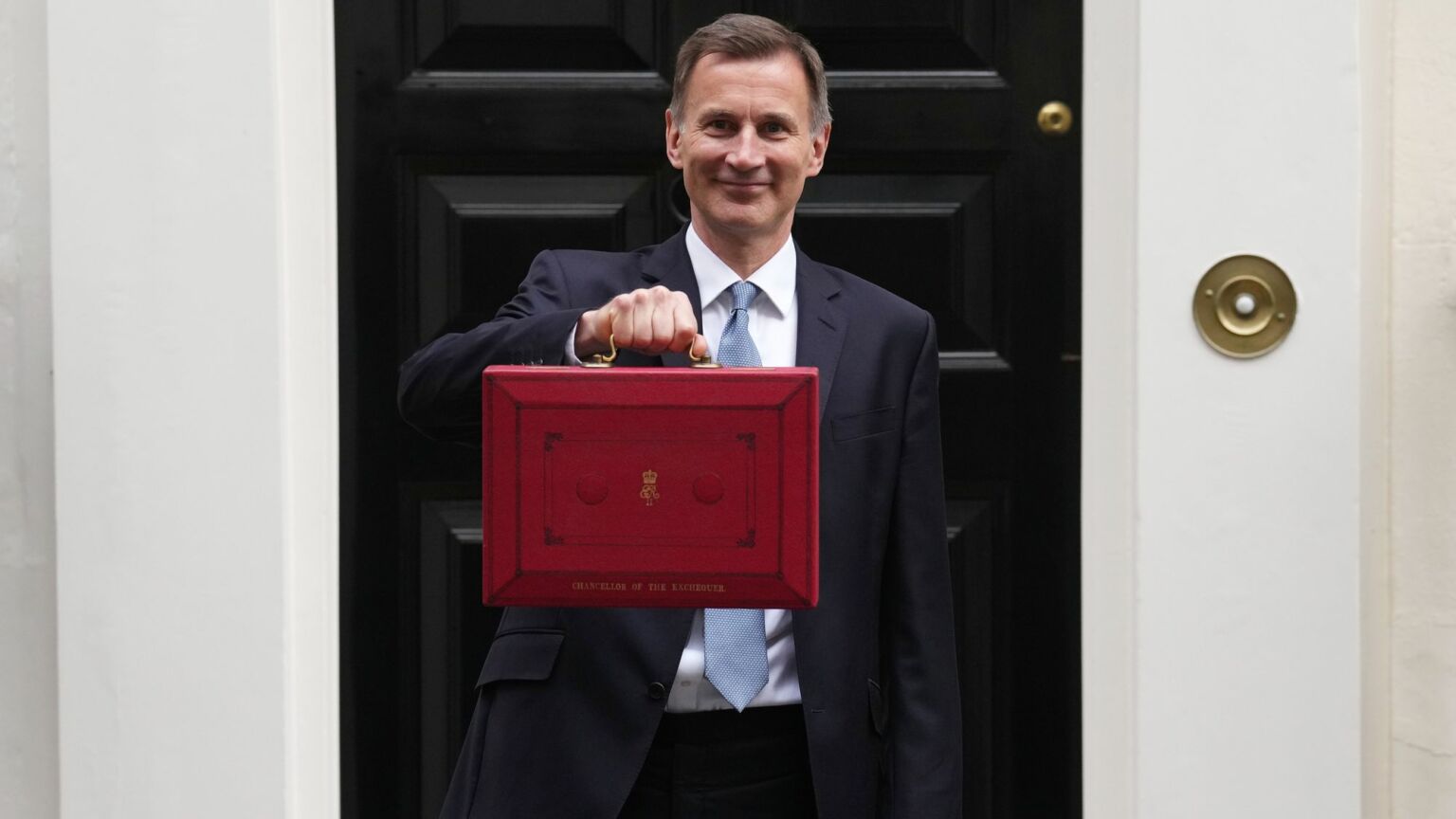

Britain’s economy is stagnant and public-debt levels remain staggeringly high. We desperately need a vigorous government response to shake up and restructure the economy. Yet, ahead of next month’s budget statement, all our political class can talk about is whether or not chancellor Jeremy Hunt will cut taxes.

Many in the Tory Party seem to believe that lowering taxes is the cure to all our economic ills. As Hunt himself put it last month, ‘low-tax economies are more dynamic, more competitive and generate more money for public services like the NHS’. This week’s news that government finances are in the largest surplus since the 1990s has sent the demand for tax cuts into overdrive.

It’s time these tax-cut obsessives stopped kidding themselves. A cut in personal or business taxes will not re-energise Britain’s entrepreneurial spirit or resolve its high-debt, low-growth malaise. The barriers holding back investment and innovation won’t be overcome with a slight reduction in income or inheritance tax. Britain’s economic slump is deep and protracted. Productivity – economic output per hours worked – has been stagnant since before the 2008 financial crisis.

Yes, we can legitimately argue for lower taxes from the perspective of personal freedom. But lower taxes won’t raise productivity levels. That can only happen through the restructuring of our economy, by shifting resources away from low-productivity businesses into higher-productivity businesses that can provide better-paying jobs. That will require a wave of creative destruction, not fiddling with tax rates.

HL Mencken once observed that ‘there is always a well-known solution to every human problem – neat, plausible and wrong’. That is the role tax-cutting plays in the Tory imagination. It’s a neat and plausible solution to economic stagnation – and it is also wrong.

Speaking to the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, Hunt argued that ‘the economies growing faster than us in North America and Asia tend to have lower taxes’. And it’s true that during the past three decades, the US and Japan and others in Asia have enjoyed faster productivity growth than Britain. They have also had consistently lower taxes relative to annual output. But it is also true that other economies that have grown faster than Britain, such as Germany and Sweden, have higher taxes. As the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Tom Josephs told the House of Lords’ Economics Affairs Committee last month, ‘there is no real evidence linking your level of tax-to-GDP ratio with economic growth’.

The assumption that low taxes lead to economic growth is not just empirically unsound. It also hugely underestimates the size of the political and cultural battle that has to be fought in order to get the economy thriving again. Successive technocratic administrations have been unwilling to make the radical changes necessary to get the economy growing again. They have prized ‘stability’ above all else, even if the price for this has been economic stagnation.

Now, none of this is to say that we shouldn’t be making changes to our tax system. There is nothing wrong with wanting taxes to be as low as possible. And there is a strong argument for vastly simplifying our incredibly complex tax codes. This would certainly boost individual freedom and minimise state interference in business life.

Last year, Jonathan Athow, a director general for customer strategy and tax design at HM Revenue and Customs, told MPs that he thought the tax system had become far too complex. He pointed out that the tax system is now designed to meet far more objectives than in the past, from aiding economic growth to pursuing all manner of ‘other public-policy aims’.

We need to get back to a situation where taxes are designed to serve their principal function – to pay for public goods. The government should abandon its patronising use of personal taxes to change our behaviour, from what we eat to how much we drink. That means no more ‘sin’ taxes, no more ‘nudge’ taxes and no more ‘green’ taxes. Let people judge for themselves what is best for them and their families.

Meanwhile, using tax reliefs, credits and allowances to encourage businesses to behave in certain ways can be just as harmful. The UK’s more than 1,000 forms of tax relief distort the behaviour of businesses. They tend to benefit older, larger firms with the greatest lobbying power, rather than those that are most dynamic and productive.

We certainly need a much simpler tax system, geared towards funding public goods. But our politicians need to admit that simply cutting taxes won’t solve our economic woes. The sooner they do, the sooner we might be able to reckon with the root causes of the UK’s stagnation.

Phil Mullan’s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Emerald or Amazon (UK).

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.