Long-read

The battle for growth

We must take on the stifling orthodoxies of both left and right.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Households in Britain are facing a really tough future. Even with the short-term energy fixes the new Liz Truss government is planning for this winter, real incomes are falling, consumer prices are soaring and power supplies are threatened. Many families will still be unable to pay for their necessities, some businesses will close and energy blackouts remain possible.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has pushed the cost of living to exorbitant levels. And so government support for households is certainly justified. But the gravity of the economic crisis calls for much bolder government action. We need policies that will transform the economy, not simply react to the latest crisis.

It is misguided to attribute today’s cost-of-living crisis solely to some ‘perfect storm’ arising from pandemic lockdowns, the energy-supply crunch and the supply disruptions from the Ukraine war. Rather, what this triple whammy has done is bring the pre-existing fragility of the West’s wealth-creating capacities to the surface. Today’s tempest has been brewing for decades. Fundamentally, the unfolding crisis reveals the precarious plight of all the advanced industrial economies – and of Britain’s in particular, as the weakest of a malfunctioning array.

For many years, writers on spiked have highlighted the dangers of rising indebtedness and of deficient investment in physical assets, infrastructure and technologies. They have argued that there are limits to societies trying to live off dilapidating resources while borrowing from the future. It is possible that this winter will be a crunch point, when those limits will become all too tangible. The fallout from decades of underinvestment in everything from social care to new technology to critical infrastructure is making itself felt.

However, for some time now, politicians have simply been responding to the latest hit to the economy. Indeed, recent governments appear to do little more than muddle through from one crisis to the next. No matter how critical the situation becomes, politicians still struggle to grasp what is required to resolve it. But by not acting, the underlying problems fester and become more profound. The failure of successive governments to invest in domestic energy production is perhaps the best illustration of the self-inflicted character of many of today’s biggest challenges.

The new government has found some sticking plasters with its caps on energy bills for households and businesses. But the only meaningful solution for today’s cost-of-living crisis is to get the economy growing strongly. Nothing else can provide families with the personal or collective means to cope with the exigencies of contemporary life. What people need most is not dependence on the latest government relief scheme, but the opportunity to secure well-paid work in a flourishing economy.

This is why Britain’s new government has to adopt a radically different path from what has gone before. Instead of muddling through, it needs to embark on a programme of extensive economic restructuring. This demands a fresh approach that goes beyond the tired formulae of tax-and-spend, tax cuts or borrowing to spend. The solution is neither a smaller state nor a bigger state. Rather, what is needed is a politically directed state. A state with productive transformation and innovation as its guiding mission.

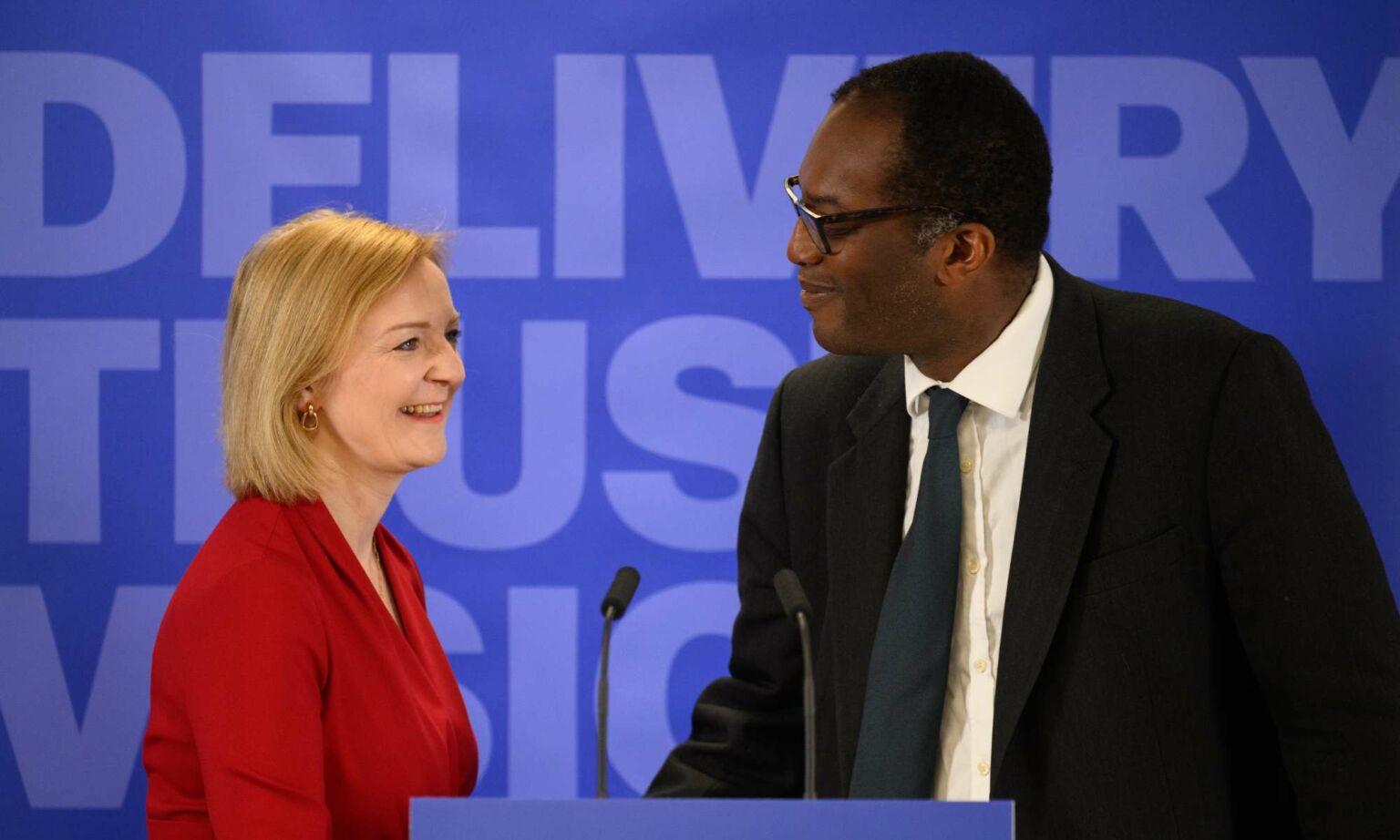

Liz Truss’s new government has, at least, made a few of the right noises. Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng claims that the Truss administration will be ‘bold’ in promoting growth. He promises it will brush aside the ‘same old economic managerialism [that] has left us with a stagnating economy’. And it will instead focus ‘on how we unlock investment and growth, rather than how we tax and spend. It is about growing the size of the UK economy.’

These overtly pro-growth sentiments are welcome. But we have heard similar from many previous administrations. We have had a long list of industrial strategies, innovation programmes and regional-development policies (remember‘ Levelling Up’?). Yet little has changed. Productivity in the UK – the amount produced by each person – has continued to flatline.

This outcome is not simply a matter of good ideas being poorly executed or implemented. It also derives from successive governments’ failure to appreciate the scale of the task at hand. And that is a cultural failing as much as anything.

This cultural failing has three key elements. First, policymakers are plagued by an intellectual shallowness, which underplays the depth of the economic challenges. Second, they adopt a fatalistic approach to economic developments, which underestimates the capacity of the state to change things. And third, the political class has evaded responsibility, with governments repeatedly recoiling from making the decisions needed to bring about an economic renaissance.

Neither intellectual shallowness nor fatalism are novel features of our political culture. But they have both been amplified by the decay of the old left-right contest of ideas over the past 30 years, and by the emergence of a new elite that has assumed cultural control of society. Today’s ruling elite holds and promotes cosmopolitan values and identity politics, often in opposition to the majority of the public. And it rejects the earlier ideals and practices of national democratic politics. Indeed, it often rejects the idea that there is even such a thing as the national interest.

To tackle today’s crisis, and to win democratic support from the public, the government needs to mount a serious challenge to these cultural tendencies.

The roots of the problem

To transcend the intellectual shallowness of our political culture, we need to recognise that the sources of today’s cost-of-living crisis go back a considerable way. While lip service is often paid to the need for growth, this rarely extends into an analysis of why growth has been so poor for so long. Politicians in recent years have tended to assert, wrongly, that the UK economy remains fundamentally strong.

Sometimes, in their complacency, politicians will boast that Britain is ‘the fifth biggest economy in the world’, in terms of GDP. But this is mainly a reflection of Britain’s decent-sized population and its past economic development. This conveniently conceals the current state of economic lethargy. On an output per person basis – a better guide to productivity and living standards – Britain languishes in 17th place out of the 38 members of the developed countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

In their more reflective moments, the UK’s leaders have sometimes noticed that poor business investment is leading to weak productivity growth. For instance, former chancellor Rishi Sunak highlighted this in his Mais lecture at the Bayes Business School in London earlier this year. But the reasons he gave for this problem were tautological: ‘Why is investment so low? My analysis is clear… businesses simply aren’t investing enough.’ Apart from offering some rather simplistic comments on how capital investment is taxed, Sunak had little to say about how business investment could be improved.

This failure to grasp the deeper roots of today’s economic stagnation speaks to more than an absence of imagination. For too long, commentators and politicians have been able to kid themselves that the British economy has been doing okay. This is partly because periods of capitalist decline rarely unfold in a steady linear manner. It is also because several coping mechanisms have been developed over the years that have disguised the longer-term atrophy.

Most significantly, Britain and other mature economies have been able to use two things to disguise our decaying productivity – globalisation and financialisation. Globalised supply chains drove down the price of imports, keeping the cost of living low even as wages stagnated. Meanwhile, greater financialisation has enabled households and businesses to take on ever greater debt to make up for shortfalls in income. The 2008 financial crisis exposed the limits of this debt-based model. And around the same time, China started to develop beyond its former role as a simple exporter of cheap goods to the West.

Today, Britain’s economic stagnation has become all too clear. Even before the spike in consumer prices of the past year, real earnings for the average full-time worker in Britain were still below where they had been in 2008. This represents a decade and a half of flatlining incomes – the biggest squeeze on living standards since the Napoleonic Wars.

The new government will not be able to pretend things will all be okay in the way its predecessors tried to. If it genuinely wants to address the deeper roots of the cost-of-living crisis, it will also need to take on two other barriers to growth today: fatalism and political short-termism.

Fighting fatalist thinking

There has always been a fatalist element to economic discussions that goes right back to the time of Adam Smith. The economy is often seen as an entity with a life of its own – as something largely outside of human control. This perspective has been reinforced by the post-1970s orthodoxy that views most state intervention in the economy as either ineffective or even damaging.

The exhaustion of capitalism’s main coping mechanisms in recent years has added to the sense that most policy levers are pretty useless for resolving economic problems. Not even more than a decade of ultra-loose monetary policy, with interest rates at near zero and vast amounts of money being printed, was able to bring about a strong recovery after the 2008 financial crisis. If anything, these policies created greater financial instability. This has reinforced the scepticism that government policy can do any economic good.

This perspective then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. When economic events are seen as relatively impervious to state action, state activism falls out of favour. And so economic weakness becomes entrenched and seems even tougher to manage. And so, although the Truss government has made a point of highlighting that Britain has a growth problem, this overdue realisation will not necessarily lead to a credible plan to fix things. Indeed, economists have been talking about ‘secular stagnation’ for many years, but most still cling to the view that the state’s power to change this is limited.

You can see this fatalism in the way economic problems are talked of as if they are natural. For instance, it has become fashionable in recent years to draw on the meteorological metaphor of ‘headwinds’ to describe anything that is holding back economic growth. Similarly, climate change and demographic trends, such as an ageing population and a slowdown in population growth, are some of the other common ‘natural’ factors that are used to explain or excuse tepid growth.

‘Deglobalisation’ has now been added to this list of factors that are supposedly restraining productivity growth. Although there is, so far, little evidence that cross-border economic exchange is in decline, there is still a great deal of anxiety about what the alleged ‘end of globalisation’ might mean for growth.

Another of these alleged anti-growth ‘headwinds’ is the idea that, in future, supply-chain ‘resilience’ will be prioritised by firms over economic ‘efficiency’, following the disruption to global supply chains caused by the pandemic lockdowns and then the war in Ukraine. We are told this will inevitably lead to higher inflation in the years to come.

All of these discussions about deglobalisation vs globalisation assume that economic developments are driven by shifting ‘tectonic plates’, or ‘big cycles’, that are global in scope and can easily overwhelm the capacities of national governments.

With government ministers increasingly forced to at least recognise that the economy is in deep trouble, you can see why they might be tempted to reach for these excuses. Attributing economic problems to outside causes, beyond regular policy control, is a useful scapegoat for governments to avoid taking the disruptive risks needed to genuinely kickstart the economy.

Can the new government push back on this fatalist culture and challenge its predecessors’ evasions? The evidence so far suggests not. Although Truss’s energy bailout is unprecedented in scope, the new government’s flagship plan for growth is focused, rather banally, on cutting taxes. Worse, many of the tax cuts announced so far are merely reversing or cancelling the rises planned by her predecessors. Besides, Truss’s apparent belief in the power of the free market suggests a broader reluctance to embrace the kind of radical state activism we need.

Taking on the technocrats

To reverse Britain’s decline, the new government needs to acknowledge and reverse the decades-long debasement not only of the economy, but also of politics. Governments since the 1980s have been shirking their political responsibilities to ensure that the basics of modern life are provided to people, both affordably and reliably. Moreover, governments have given up on their previous raison d’être of winning over the public towards a vision of a better future.

Of course, politicians still want to win elections, but the contest has become much more about which leader can provide a safe pair of hands on the Whitehall tiller. The scope of economic policy has been reduced considerably. Economic debate today is centred primarily on ‘managing’ the economy to avoid disrupting things too much. The old political virtues of long-term planning and follow-through have drained away. Today’s politicians are obsessed with the short term. So it is no wonder that society seems to lurch from one pressing crisis to the next.

In his final major policy speech as prime minister, Boris Johnson revealed that this cultural short-termism is not hard to recognise, even from inside Downing Street. Notably, he backed the construction of a new nuclear plant at Sizewell. Tellingly, he presented his stance as a counter to the political ‘myopia’ that had delayed government commitment to nuclear for many years. He described this as a ‘chronic case of politicians not being able to see beyond the political cycle’.

Johnson’s attack on government ‘short-termism’ was certainly warranted. But it might have been a little more meaningful if his own party had not been in government for 12 years, and if he himself hadn’t waited until his final days in No10 to make the rebuke.

Truss’s early statements suggest she has not yet come to terms with the repeated policy failures of the three administrations she served in. During her campaign for the Tory leadership, she frequently blamed civil-servant obstructiveness, Treasury orthodoxies and central bankers’ complacency for the economic mess she was about to inherit. She was keen to shift the blame to anyone but the past few administrations.

Anyone can criticise the decisions taken by technocrats and regulators, but we shouldn’t forget who gave them their power. From the 1980s onwards, successive governments of all stripes outsourced their responsibilities to unelected bureaucrats. They passed laws setting up ever more extensive ‘regulatory frameworks’ and ‘quangos’ to oversee economic life. Certainly, the technocrats often share the same myopic lack of vision as our current crop of politicians. But it is ultimately the politicians who have allowed these often insecure and out-of-touch officials to hold so much influence over public policy.

Most state interventions in the economy in recent years, whether they have come from technocrats or elected ministers, have been reactive and short-sighted. We need the next government to add some substance to Johnson’s criticism of political and economic short-termism. The best way to kickstart this would be to re-establish the authority of elected politicians over the technocrats and officials.

The battle to come

The barriers standing in the way of economic growth are not natural – they are cultural. Any government that is serious about reviving the UK’s economic prospects will have to take on the stifling orthodoxies of our cultural elites.

The ascendance of a new set of cultural values has reinforced the intellectual shallowness, passivity and short-termism that have plagued Britain’s economic debate. Indeed, much of the fatalism we see in economic discussion today is echoed in our cultural debates, where ordinary people are viewed by our elites as too vulnerable, too selfish or too prejudiced to properly understand their own interests and those of the nation.

Even the urgent need to build affordable energy capacity is ultimately a question of culture. Antipathy towards domestic energy production, for instance, speaks far more to cultural prejudices and to a culture of risk-aversion than it does to any science of climate change.

Besides, in order to win public support for a potentially disruptive programme for economic change, the government will need to show that it is on the side of ordinary people. And culture is fundamental to people’s everyday lives. By fighting against the minority view of the elites, and instead fighting for things like family, freedom and tolerance – things cherished by so much of the population – politicians can start to establish a new rapport with the electorate. We can start to treat the public as the creators of our collective future. Only then will the arguments that need to be had in order to transform the economy gain popular traction.

Economic decline is not inevitable. But it will take a serious cultural reckoning to bring about the economic renaissance we all deserve.

Phil Mullan’s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Emerald or Amazon (UK).

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.