Long-read

The Pet Shop Boys and the exhaustion of pop

Over their four decades, the marginal has become thoroughly mainstream.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

By the time he’d made it on to record and into the charts, Neil Tennant had lived many lives. As had many of those listeners who came on board with the debut album, Please, in 1986 and stayed interested in, if not always loyal to, the Pet Shop Boys canon.

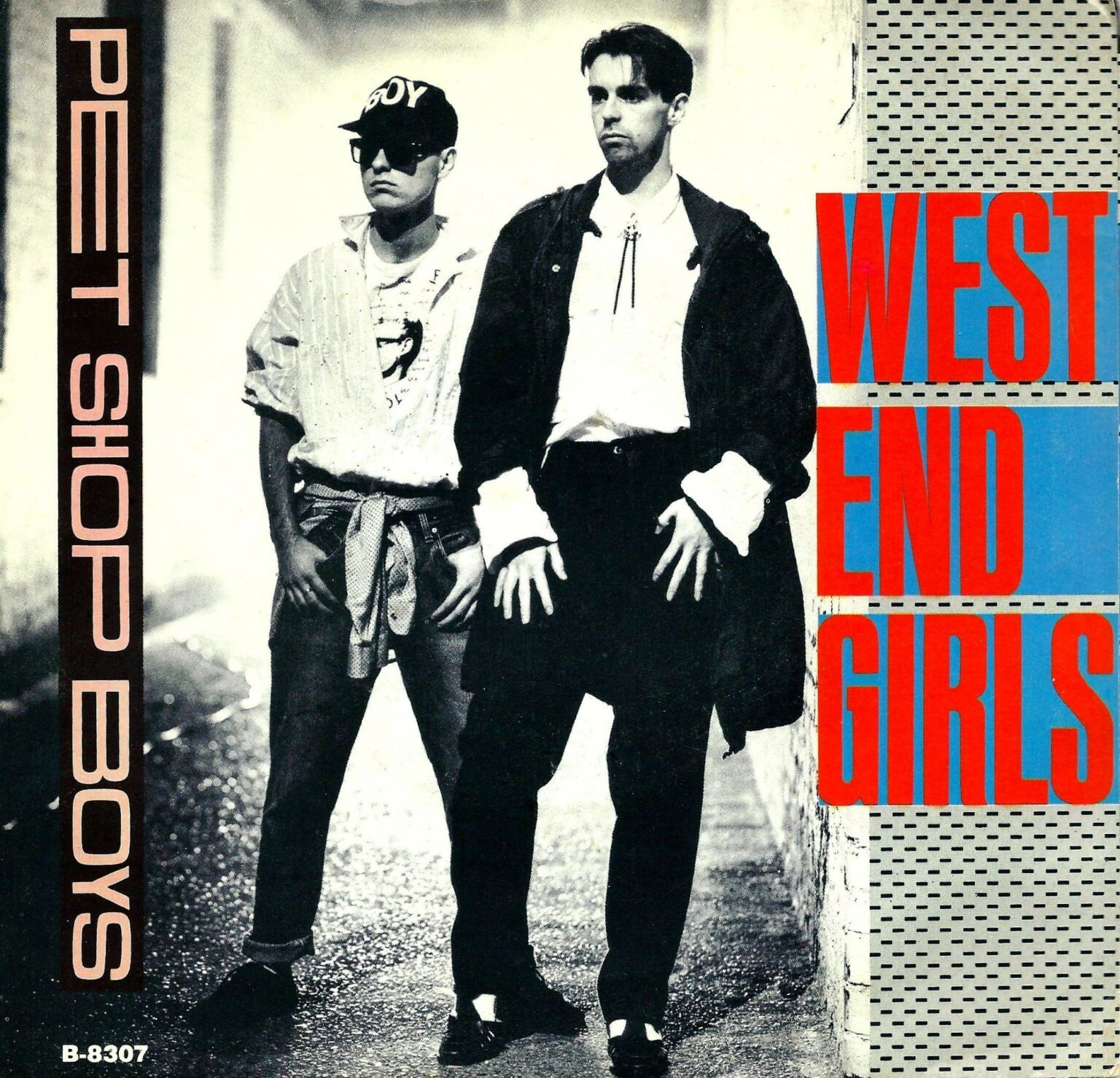

Much of this canon features in the forthcoming Pet Shop Boys collection, Smash, which covers the duo’s career by way of 55 singles recorded between 1985 and 2020. Beginning with ‘West End Girls’, released the month PC Keith Blakelock was savagely murdered during the Broadwater Farm riots, Smash concludes with a song about a boy who won’t leave home, during the peak of the Covid pandemic. If a Pet Shop Boys line wasn’t on our lips or on our minds, it was out there somewhere as the world changed – as our world changed when love, loss and death punctuated the odd party, club night or wake. After friends have gone the way of family members and all flesh, our faculties will desert us, but those lyrics will linger on: ‘This is our last chance for goodbye. Let the music begin.’ The songs turn up in the most unlikely venues: a track from Actually plays pianissimo in the waiting room at a doctor’s surgery; ‘What Have I Done to Deserve This?’ can be heard in a boisterous Morrisons café at breakfast time.

Neil Tennant, born in 1954, is older than those of us born at the beginning of the 1960s, yet not old enough to be the funny uncle he sang about on the album, Introspective. He’s more the elder sibling, the older brother. My one sibling, my older brother, died in his late thirties in the early 1990s, between the albums, Behaviour and Very. He would now be the same age as Tennant, who turns 70 next year. It’s the age pop stars are never expected to reach. Many of those who accompanied Tennant into adulthood – and his fellow Pet Shop Boy, Chris Lowe, through adolescence – didn’t make it. Marc Bolan was halted by a car crash at 29; David Bowie died days after making 69. Lou Reed reached 71. Bryan Ferry remains with us.

These figures, those fashions, filled us with an aesthetic, an outlook that took us in the direction of the future and the past, the retro and the modern. For some it took them where books had already taken them. The novels of Evelyn Waugh introduced Neil Tennant to another world; one that he wanted to be part of. Before he got to join it, there were other lives to live: a stint with amateur theatre as a teenager; fronting a folk group as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, when the hippy hour was succeeded by glam rock’s big moment.

At 17, Tennant declared, unashamedly, he would one day be a pop star. Amid power cuts, three-day weeks, three television channels and one Top Twenty, pop music enlivened the lives of the young and the dispossessed raised in poor urban postcodes, ports (Tennant, North Shields) or resorts (Lowe, Blackpool). Or at least it did for those who harboured a certain sensibility. It was a private code, rather like the ‘camp’ Susan Sontag defined a decade earlier. But this wasn’t exclusively the preserve of homosexuals, as she believed camp to be. It was a credo observed by those who didn’t want to be pinned down to one tribe.

Still, names were needed. And in a 1976 Harpers & Queen essay, writer Peter York came up with one for these ‘creators of the dominant high-street style aesthetic of the Seventies’: ‘Them’. They made the supreme sacrifice, York wrote, by forgoing looking sexy for looking interesting. But only those in the know could read the references and decipher the code.

Key figures within the group combined a camp aesthetic with an art-school sensibility. It included the filmmaker, Derek Jarman, who would later direct a Pet Shop Boys video. Some came from money or with a pedigree. Some lived in poor homes in posh neighbourhoods. When the big Biba store closed in 1975, Kensington High Street was replaced by King’s Road as the capital of their world. It was where Neil Tennant found a home early on, and where he met Chris Lowe in 1981 and formed the Pet Shop Boys. The young and dispossessed who arrived from the suburbs, the provinces, or simply crossed the river to SW3, were given the title ‘junior grade Them’ by York. His celebrated essay was published as the punk attitude was taking hold. He cites the high season of ‘Them’ as the summer of 1973. This was the moment Neil Tennant, fresh to London (‘I left from the station / With a haversack and some trepidation’) took a job at the British Museum before beginning college. His dyed hair belonged on Bowie; his white Oxford bags belonged on Gatsby; and his women’s platform shoes belonged on every queer outsider who made the leap from glam to Them, and discovered an alternative adult world of polymorphous sexuality, swish androgyny and tacky transvestism, in which they were often a bystander and always a cheerleader.

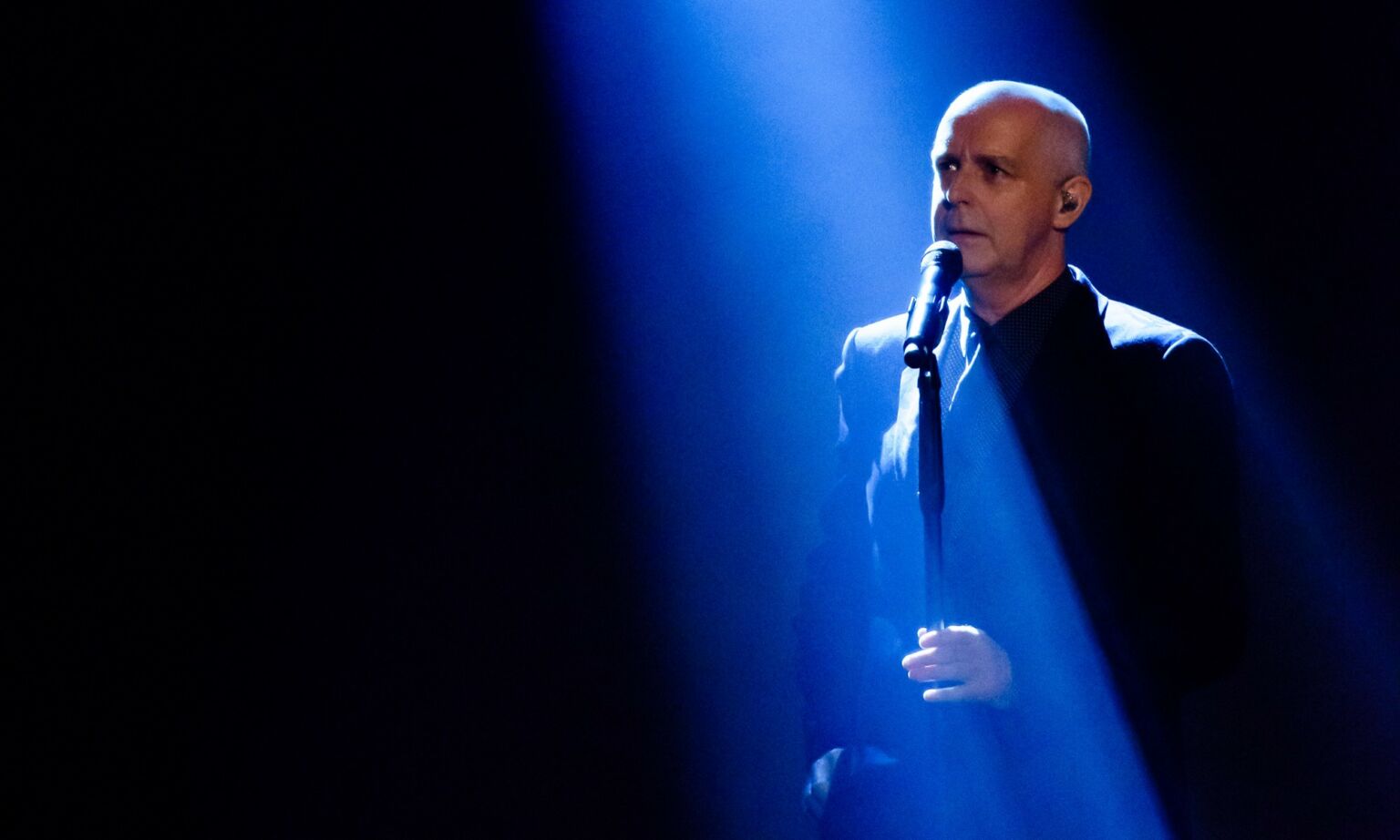

The Pet Shop Boys covered all the above in the song ‘Requiem in Denim and Leopard Skin’ in 2012: ‘I visualised the flashbacks: school, punk rock, success… Biba’s closing sale… Bryan in a tux… Adam’s in a Jarman film…’ Tennant wrote it as an elegy for a friend, but it drew on his experience of an era that blossomed into the new romanticism and gender-bending. Trends he absorbed and then discarded when he emerged alongside Chris Lowe, phoenix-like, from the embers of this era in the mid-1980s. The Pet Shop Boys were different even then. Suitably dressed and stationary, Tennant declared lyrics and relayed songs rather than performed them. The music made you want to dance; the words made you want to read.

As a thirtysomething, he was old to be making his debut as a pop star, having missed his moments during the movements that passed during his formative years. He was a grown-up: he’d settled into education and settled down to jobs, the last of which had been that of assistant editor at Smash Hits. When he became the pop star he once announced he would be, he didn’t welcome it with relief and gratitude. Instead, when making his debut on Top of the Pops in December 1985, en route to the No1 spot, he appeared haughty and aloof. ‘Don’t look triumphant’, Chris Lowe advised him before the music and the miming began. From that moment, another life had begun for Tennant. One that brings to mind a line from Waugh’s Decline and Fall, the book that started it all: ‘If everyone at 20 realised that half his life was to be lived after 40…’

Now the Pet Shop Boys have passed 40. Neil Tennant is heading to seventy, and Chris Lowe isn’t far behind. It’s 50 years since a roll call of dead pop stars showed us all – Tennant, Lowe, the class of ’73 – that the good life was somewhere out there. It was rumoured to be glamorous, gaudy and a tad fey. Much of what drew us to the margins back then has found its way into the mainstream. All of which has come at a cost. There have been gains; there have been losses.

On the margins no more

From the vantage point of the present there is something quaint about David Bowie playing gay for a day, and Lou Reed dating a transsexual. Even the Warhol Factory fodder cast as ‘superstars’ by the artist, and immortalised in Reed’s ‘Walk on the Wild Side’, appear endearing in their efforts to pay homage to old Hollywood starlets. And they did so despite the hard drugs and harsh drag that determined their lives, and the heroin addiction and hormone treatment that hurried their deaths along.

Once Warhol protégé Candy Darling carried tampons in a translucent handbag to pass himself off as a ‘she’. Now Dylan Mulvaney is promoting Tampax on TikTok, and the inverted commas have disappeared. In place of the anomalous transsexuals and transvestites that made us odd outsiders avert our eyes and prick up our ears, there is now a militant trans lobby which is treated as a protected species. A man can seemingly spend three months in a frock or a fright wig and be classified as female no matter how evident his penis and his five-o-clock shadow. Sam Smith is in nipple pasties, Eddie Izzard is in ‘girl mode’ and anyone who refers to them with the wrong pronouns will incur the wrath of the Twitter mob. I’d rather hoped this is what the Pet Shop Boys meant by ‘Give Stupidity a Chance’ from 2019. But I fear it wasn’t.

Like ‘I’m With Stupid’, the 2006 song about Tony Blair’s relationship with George W Bush, ‘Give Stupidity a Chance’ was another rare excursion into politics. These songs took us beyond the arguments Culture Club proffered when Boy George attempted politics, informing us that ‘war is stupid’ and people are, too. The Pet Shop Boys are too smart for such simplicity; too smooth for those hobbies picked up in student bars, or found on badges, and dragged into middle age by actors and musicians as a form of method activism. Around the time of Pet Shop Boys’ Agenda EP (2019), Neil Tennant rightly suggested that politics needed to get serious again. ‘I can imagine writing a Trump-inspired lyric’, he said. ‘Unfortunately stupidity is a new trend in politics.’

But blaming the drift towards imbecility on Trump’s election or Brexit, as Tennant seemed to be doing, was misleading. The reaction to the Brexit vote from the Remain camp surpassed the ridiculous; and those that dismissed much of the US electorate as ‘deplorables’ contributed to the election of President Trump. Moreover, the radical and the reactionary have been reversed today. As Nick Cave pointed out recently, going to church and being conservative is the modern way of ‘fucking with people’.

This year, the Pet Shop Boys released the Lost EP, containing songs recorded five years earlier. The title refers to a society that appears to be uncertain where it’s heading and shaky about its survival. The old order is rumoured to be crumbling, with ancient, straight white men cast as the fall guys. Posh students deface art and posh pensioners block roads. And race hustlers demand preferential treatment in the present and reparations for the past. Yet those intent on dragging us back to a darker age, or simply eradicating ‘whiteness’, appear more lost than the targets they attack. And they are too clueless to anticipate what might appear in the clearing if they succeed.

The equalities lobby – most notably one-time gay-rights campaigners Stonewall – has perhaps lost its way more than any other pressure group. For it to acknowledge that society has progressed on its pet issues would leave it without an objective, a grievance, or funding.

We have come a long way since Neil Tennant put on girl’s shoes, David Bowie put on make-up and Lou Reed declared: ‘We’re coming out / Out of the closet.’ So far, in fact, that gay men and women are now accused of transphobia for being exclusively attracted to those who are the same sex as them.

Over the course of Tennant’s lifetime, homosexuality became infantilised in order for it to be accommodated and accepted. Activists aligned it with a crass word (‘gay’) and crass phrases (‘coming out’), while rallying round a rainbow flag. Pride marches got the ‘gay’ movement off the starting block; the pink pound took it to the finish line. Coming from an era when queer outsiders didn’t wish to pin themselves down to groups and names, it was no surprise that Tennant was late to the party when it came to confirming his sexuality in the press. ‘What I like about the queer thing is there’s a lot going on under the surface’, he said recently. ‘The gay thing, I always felt, was homosexuality as a sporting activity, doing aerobics to Kylie. As opposed to Cambridge spies and Joe Orton and that whole world of subterfuge. Which instinctively I feel more in common with, rightly or wrongly.’

Now the marginalised have found a platform in the mainstream, any claim to being revolutionary and disenfranchised is tiresome at best, and tragic at worst. The current crop of activists – whatever the battle – have not inherited the mantle of those in the past who put themselves on the line and pushed for change in less enlightened times. They are the privileged products of an affluent consumer society. They freely choose their causes the way they pick their gender and their pronouns. To paraphrase the Pet Shop Boys, ‘They’re S-H-O-P-P-I-N-G. They’re shopping.’

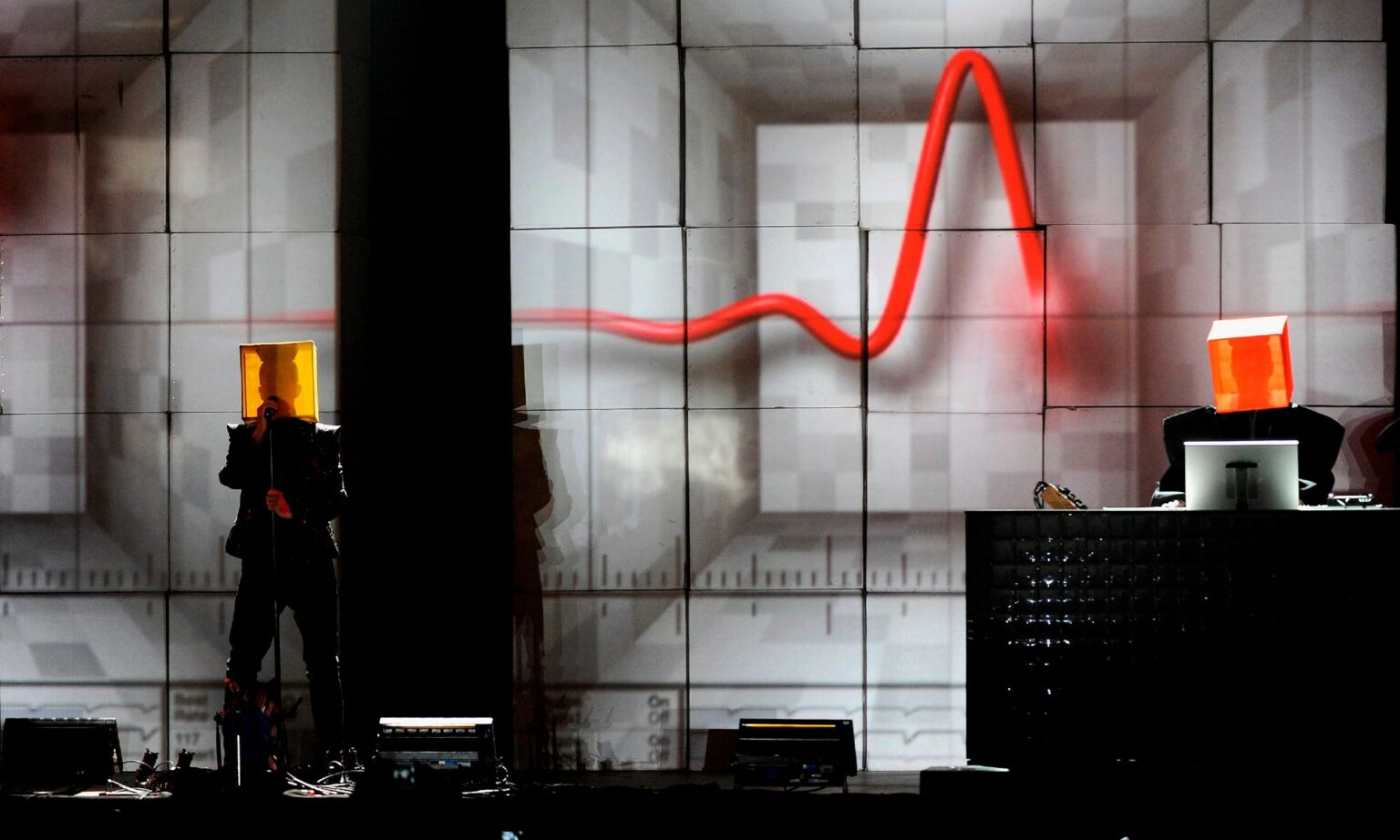

Throughout the changes of the past four decades, the Pet Shop Boys, haughty and aloof in funny hats, have commented on subjects rarely featured in pop songs and absent from dance music. As they put it in the sublime ‘Vocal’ (2013): ‘Everything I want to say out loud can be sung.’ They cite this track, along with ‘Being Boring’ (1990) as the point when they produced something magical. Yet there have been regular flashes of brilliance.

There have been lacklustre moments, too, as you’d expect in a lengthy career. Sometimes the songs weren’t as inspired as the topics and the titles (‘This Used to Be the Future’); sometimes they were too formulaic and the affiliations too faggy (‘Absolutely Fabulous’).

Despite this, and beyond the archness and the irony, a seriousness has always been evident. Death has reared its head as the duo steer closer to it, but it was present in their work from the 1980s when the AIDS epidemic cast a giant shadow. Songs such as ‘It Couldn’t Happen Here’ or ‘King’s Cross’ provided a moving counterpoint to the evangelical extremists sermonising on AIDS, declaring it to be God’s punishment on homosexuality and the society that tolerated it.

Just as offensive as reactionary zealots’ exploitation of AIDS was the response among those artists who claimed it had taken the most brilliant, beautiful and creative among us. As though this were a greater loss than the plumbers, telecom engineers who were our big brothers, taken out by common-or-garden cancer, also buried long before their time. One of the casualties of the epidemic, Derek Jarman, giving stupidity (and ignorance and disrespect) a chance, even compared AIDS to the genocide of the ‘lost generation’ in the First World War. Except that those taken out by AIDS, according to Jarman, were ‘making love not war’.

Before death, comes old age for those that get to live more than half their life beyond 40, as Evelyn Waugh put it. This too, the Pet Shop Boys addressed in the 2012 album Elysium. (‘You’ve been around but you don’t look too rough / And I still love some of your early stuff.’) Pop music itself is in its dotage, and not truly equipped for catering for those close to its age still active in it. While some of their surviving contemporaries from the 1980s reform for reunion tours, or have their legacy covered by a tribute band, the Pet Shop Boys remain current, modern, haughty, aloof and dignified. But for them, too, along with those of us who were part of the class of ’73, the end is closer than the beginning, and it might come sooner rather than later. None of us know when it will be ‘our last chance for goodbye’. As the saying goes, when the ice is breaking beneath your feet you keep dancing. ‘Let the music begin.’

Michael Collins is a writer, journalist and broadcaster. He is the author of The Likes Of Us: A Biography of the White Working Class.

All pictures by: Getty.

Except first in-article picture, by Joe Haupt: published under a creative commons license.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.