Fiddling with taxes won’t fix the economy

Neither Sunak nor Truss has an answer to Britain’s economic crisis.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Britain’s economy is in a horrendous slump. It is now doing worse than any other advanced industrialised nation. And this dire performance goes way beyond the supply disruptions caused by the Covid lockdowns and the war in Ukraine.

Productivity levels have been flat since the mid-2000s. This represents the worst period for productivity gains since the Industrial Revolution. Living standards are falling as a result. And with most wage increases falling way behind the recent surge in prices, the hardship is only getting worse.

Meanwhile the combined level of public and private debt has never been higher.

This grim combination of record indebtedness and anaemic growth is desperately calling out for a vigorous government response to shake up and restructure the economy. Unfortunately, the two lightweight contenders for Britain’s next Conservative Party leader and prime minister have not heeded this call. Instead, all Rishi Sunak or Liz Truss have been able to offer is a choice between tax cuts now versus tax cuts a bit later. The media may claim that this shows an ‘enormous’ gap between the candidates’ economic policies, but that is just empty hype. Both Sunak and Truss share the same illusions about taxation’s ability to revive or depress the economy.

Taxes are simply a means to fund the bulk of government spending, with the balance financed by borrowing. Modifying tax rates may affect public finances but the impact on the economy will be negligible. Proposing to use tax policies to tackle Britain’s economic slump is like bringing a water pistol to a gunfight.

Sunak and Truss would disagree of course. They claim that tax cuts – either now as Truss proposes, or later when combined with ‘sound’ public finances, as Sunak argues – will provide individuals and companies with more money and incentives to boost economic activities. This, they argue, will then lead to higher growth.

This is a facile thesis. It assumes that the market economy operates primarily through the aggregate of spending across the economy, including by business leaders. This focus on the appearance of capitalism, on consumption and demand, ignores the economy’s inner workings and core problems. These lie not in consumption and demand but in production and supply.

Tax-cutting policies are usually counterposed to the misnamed ‘Keynesianism’ of old leftist tax-and-spend policies. But both tax-cutting and taxing-to-spend policies actually have a lot in common. They both view capitalism’s economic difficulties in terms of inadequacies in demand. Thus, growth in output is thought to be driven predominantly by demand rather than the circumstances and development of the production process.

This is why there is so little difference between the positions of the Tory leadership candidates and the Labour Party. They both remain attached to the stale dogmas of postwar economic thinking. They share the same misconception that economic activity is driven ultimately by spending and demand. They believe that if people and businesses spend more, possibly invigorated by tax cuts, then demand for goods and services increases, which spurs on productivity growth. This is back to front. Without things being produced there is no wealth being created to generate incomes, profits, tax revenues and increased spending.

This explains why Sunak as chancellor was unable to fulfil his tax-cutting desires and instead had to raise taxes to the highest levels since the late 1940s. Because the country-wide production of wealth by people and businesses at lower levels of taxation has not provided sufficient state revenue to pay for the collective requirements of society today.

The public budget is provided for through current taxation or from public borrowing to be paid from future taxes. Both are at record levels not because that is what the government wants, but because of the weakness in productive output. The consequence is that tax-cutting was and is only really feasible if economic output is much higher. This shows that the production of wealth is primary, and its consumption (spending) is secondary.

Thus fixing production comes before taxation and spending. The priority should be to work out why productive activities in Britain are anaemic. One reason, for example, is the plethora of low-productivity zombie businesses, sustained largely by state intervention.

The primacy of production also explains why government fiscal and monetary policies have become less and less impactful as the economic depression has deepened over the past half century. In the immediate postwar period, business activities were more open to government stimulus. Following the war-time restructuring of production there was a renewed, though temporary, dynamism to capitalist growth. As a result, government spending measures were able to fuel existing productive activity.

But as the barriers to productive investment became more embedded during the 1970s, government stimulus packages proved less effective. Hence the current paradox: the state has been intervening more aggressively in the economy than ever before, but with ever diminishing returns. You can encourage a healthy horse to run faster, but kicking a dead one, or a moribund one, has rather less impact.

We should not expect much of an economic boost from any upcoming tax cuts. Just a brief look at recent economic history should dispel the illusion that taxes are crucial to growth. Thanks to looser monetary policies, money has been easier to get hold of by businesses and individuals than was the case during the postwar boom. Yet growth has been much slower. This shows that having access to more money does not automatically lead to businesses and people spending it productively, or at all.

When households do have some spare cash and decide to spend it, this doesn’t necessarily lead to more productive investment by businesses. Those investment decisions are mostly motivated by the anticipated profitability of production not by expectations over demand or concerns about future levels of corporate taxes.

Likewise many businesses have not been short of funds to invest since the 1980s. But this finance has not been invested in innovation and better technologies. Instead it has been returned to shareholders, used for other forms of financial engineering, or for acquiring other existing businesses, none of which contributes to increasing productivity.

There is also no empirical correlation between how business executives feel – what Keynes called their ‘animal spirits’ – and the long-term decline in business investment. The CBI’s surveys of British ‘business confidence’ over the past half-century show it oscillating in line with the business cycle. In upturns business leaders express more confidence than in downturns. But since the 1970s, these feelings have been irrelevant – rates of investment have steadily fallen over the decades regardless.

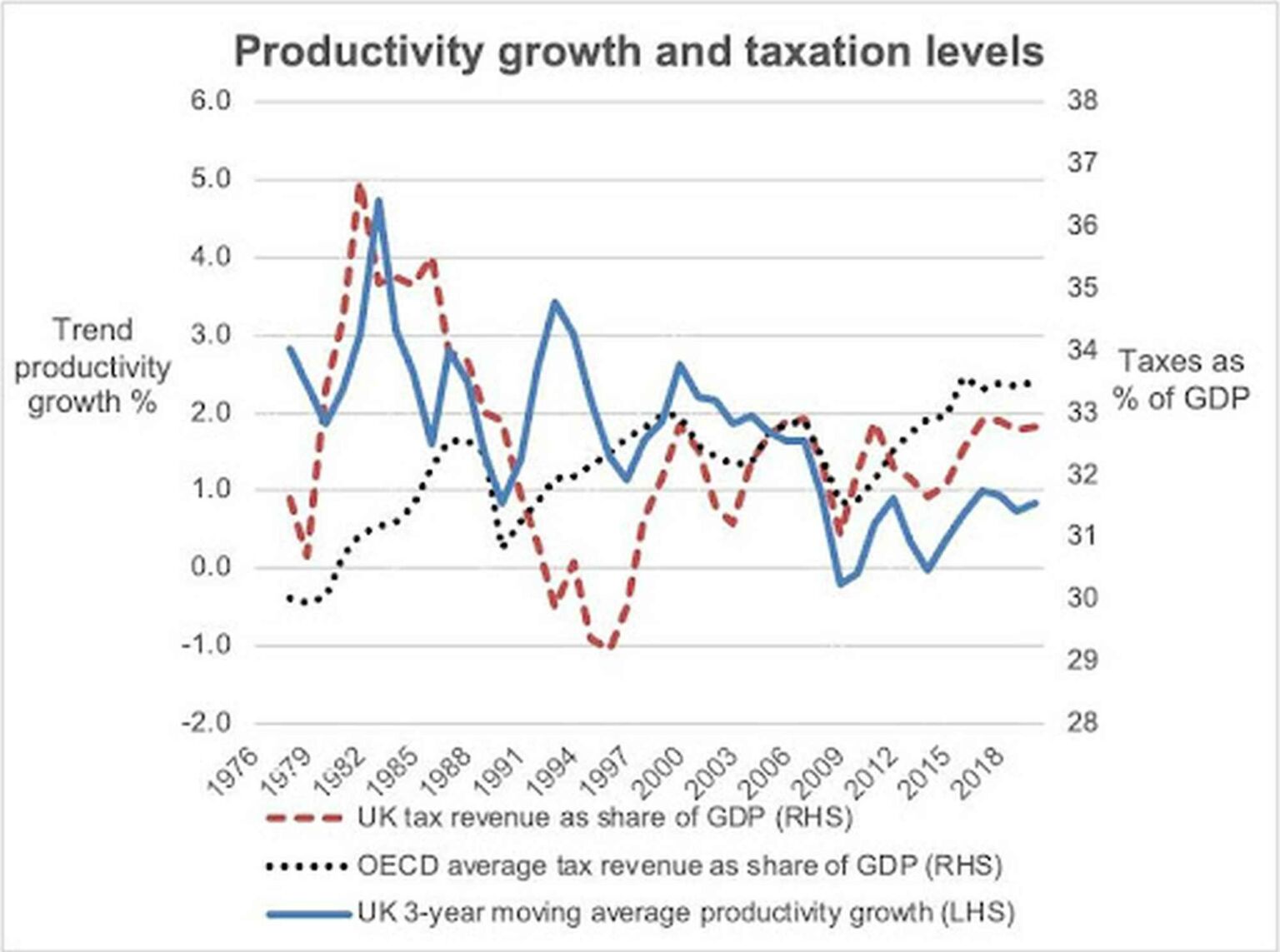

There simply is no causal relationship between tax rates and economic growth. Indeed, there is no discernable relationship between swings in taxation levels and movements in productivity, as measured by output per hour (see chart one). Productivity growth did briefly accelerate in both the early 1980s and the early 1990s. But in the first period this was accompanied by rising taxation and in the second by falling taxation.

It is reasonable to point out that there could be a time lag between tax changes and economic growth. But longer-term empirical trends suggest otherwise. We can see in chart one that from the start of this century, Britain’s average tax levels relative to GDP – the dashed line – have been below the 1980s. But trend productivity growth – the solid line – has slowed considerably between these periods, which refutes the presumption that cutting taxes enhances economic growth.

Also, for most of the time since the early 1990s, British taxation levels have been below average OECD levels – the dotted line – reversing Britain’s previously relatively higher taxation. Yet since these relatively lower taxes became the norm in Britain, it has been one of the slowest growing of the industrialised economies. Productivity in Britain fell by more than two-thirds from an annual average of 1.9 per cent in the 2000-2007 period, leading up to the financial crisis, to 0.6 per cent during 2011-2019. That was a sharper slowdown than that across the mature industrialised economies as a whole, where productivity growth fell by less than a half from 2.1 per cent to 1.2 per cent. Again, this is the opposite of what the ‘tax cuts equal growth’ creed would suggest.

Moreover, some developed countries with consistently higher taxes than Britain have higher productivity rates, too. In every year since 1972, French taxes have been significantly higher than Britain’s. Yet on the eve of the pandemic, the productivity level across Britain was about one-fifth below France’s. Britain’s relative under-performance compared to other higher-taxing developed countries further refutes the notion that lower taxes are necessarily good for economic dynamism.

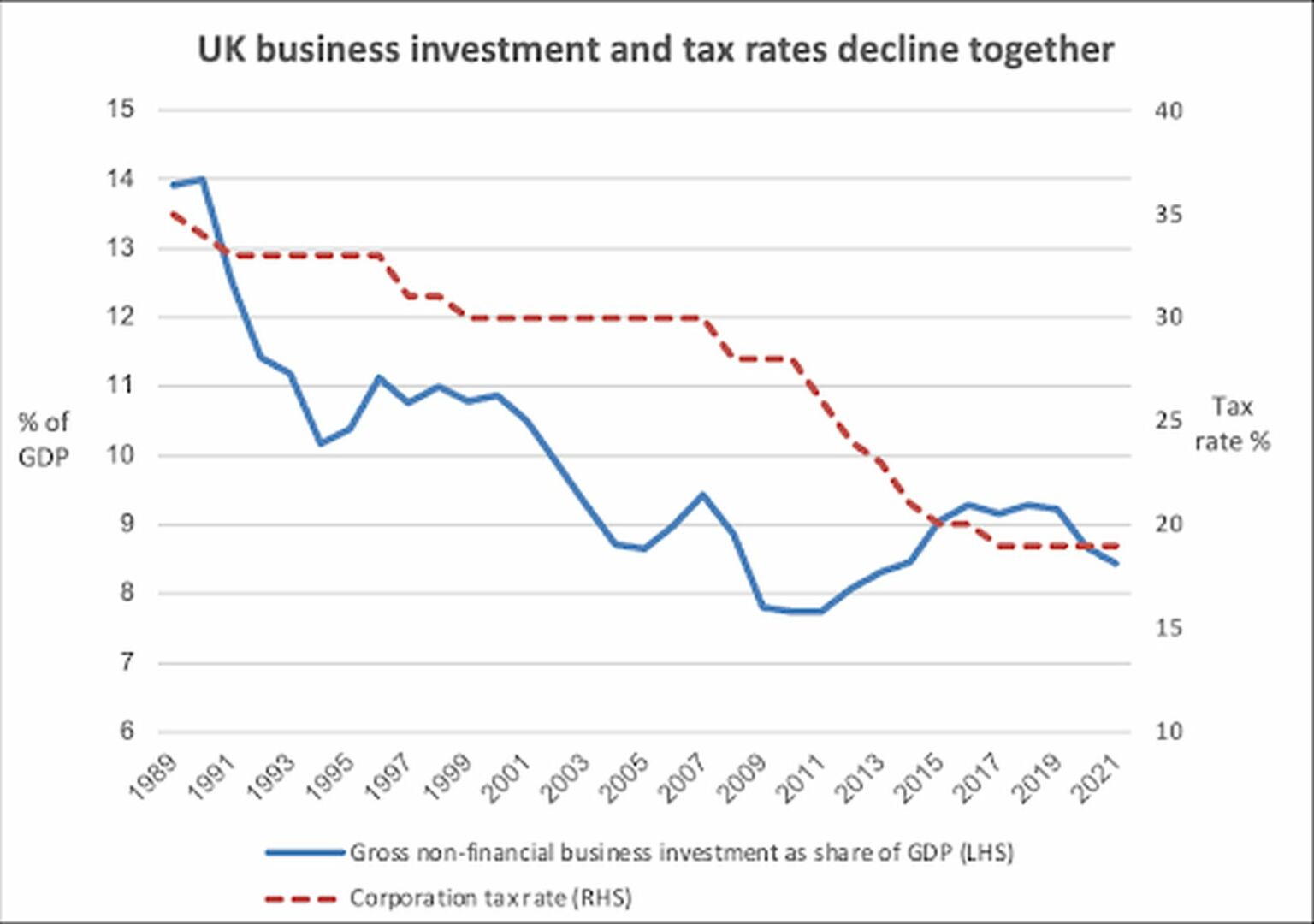

This is even clearer in relation to Britain’s levels of corporation tax. So while Britain has for a long time had the lowest corporation tax rates within the G7, its business investment levels are also the lowest. Indeed, as chart two shows, Britain’s tax rates on business profits have been going downwards since the 1980s – as have business investment levels.

In summary, tax reductions have no determinate effect on business investment and therefore do not contribute to improved productivity performance and economic growth.

If the government is serious about tackling our dismal economic situation, it needs to drop its fixation on taxation. And it needs to lead with a genuine plan for economic transformation to drive productivity growth and lift living standards. Anything else is just fiddling while the economic crisis deepens.

Phil Mullan’ s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Emerald or Amazon (UK).

Main picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.