Would Proust be published today?

À la Recherche du Temps Perdu puts the conservatism of modern publishing to shame.

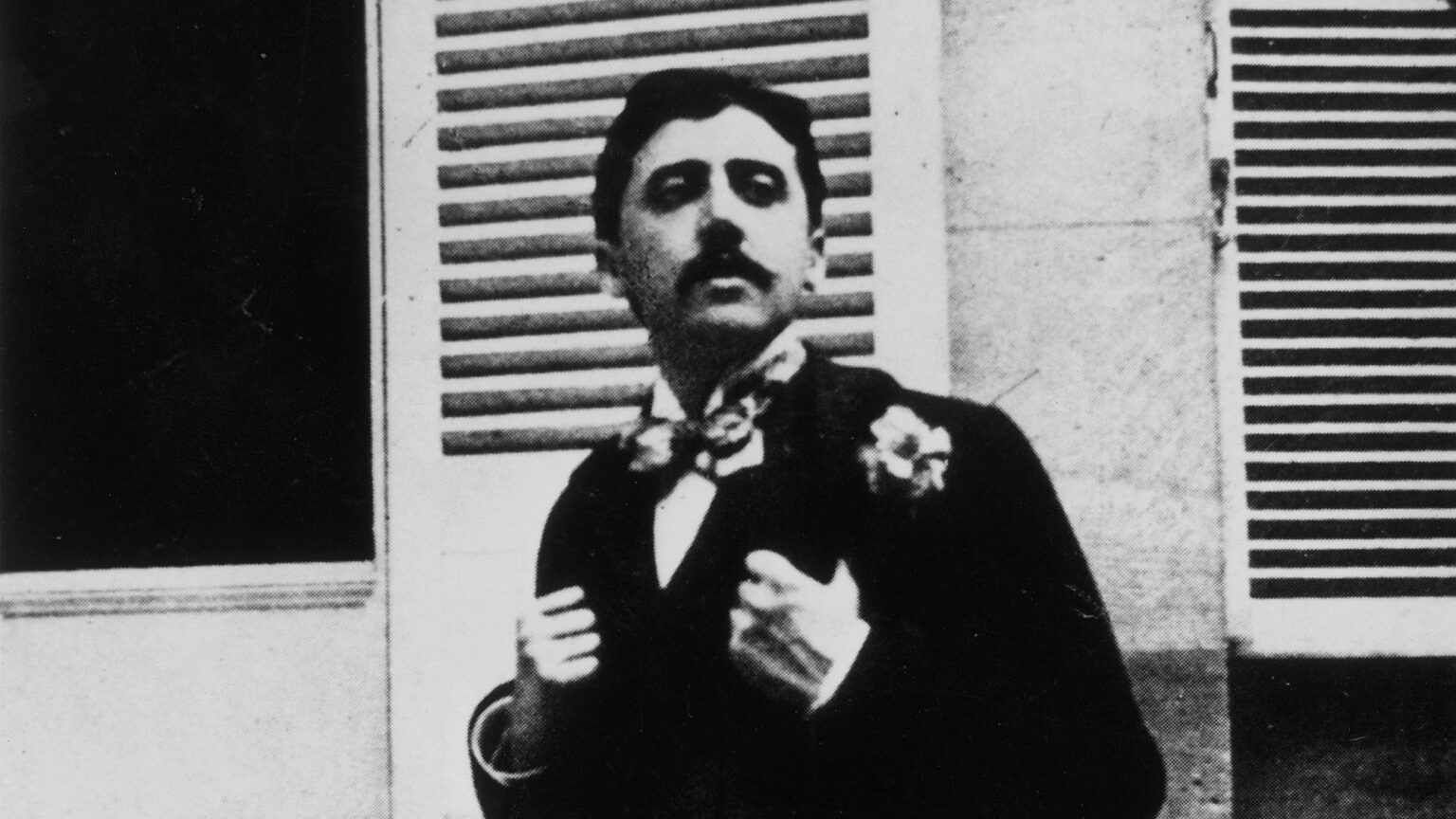

This year marks the centenary of the English translation of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, the classic modernist novel written by Marcel Proust. The anniversary reminds us to take stock of how important it was at the time, its influence on the rest of 20th-century literature and above all, why it is more important now than ever before because of the encroaching postmodernism of our times. Although the novel’s unbelievable length – its word count is around 1.27million – can make it intimidating for first-time readers, it is an essential text if you want to understand our era of identity politics and its obsession with authenticity.

A good place to start, if you want to dive into the novel or have read it before and found the long sentences a little much, is Living and Dying with Marcel Proust, a new book by Christopher Prendergast. He was the general editor of a reissued English translation of the novel published in 2002 and knows his Proust inside and out. He explores the essence of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, and provides the most definitive account of the novel’s charms on record. Living and Dying even proceeds in a Proustian fashion, covering the essential concepts of the novel, such as the importance of the five senses to our everyday experience, the passage of time as it relates to memory and, of course, the need for one’s mother, all as it dips in and out of both time and the novel itself.

Although Proust was a thoroughly modernist writer, where playing with form was paramount to him – as Prendergast’s book beautifully points out, Sigmund Freud thought the novel worthless since he felt Proust had no sense of the passage of time, surely one of the strangest reviews À la Recherche du Temps Perdu has ever received – he is at the same time praised as the godfather of auto-fiction. This is a form of novel writing in which ‘realness’ and ‘authenticity’ are praised over all other things, including the quality of the writing itself. Yet not only would Proust have surely rejected such a concept, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu is also laced with ‘falsehoods’ if the book is be taken as auto-fiction, which would mean a reflection of his life with no omissions or corrections. The most obvious example being the fact that Proust was, in actuality, gay. His novel, meanwhile, dwells heavily throughout its entire middle section on the narrator’s relationship with his girlfriend, Albertine. In other words, whatever else it might be, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu isn’t an autobiography, nor did Proust mean it to be taken as one.

In the 21st century, the publishing industry has become obsessed with authenticity – for the voice to be ‘real’ somehow, as opposed to fictional in a more traditional sense. This is a counterpoint to the modernist novel, of which À la Recherche du Temps Perdu is a shining example, where playing with form, being experimental, was key.

Experimentation in fiction involves imagination as well as the risk of offending people. In playing around with ideas and getting into the heads of characters who are different from oneself, you may be exposing deep truths that some people don’t want to hear. Proust certainly offended some people with his novel when it was first published, with its frank discussions around the nature of homosexuality, and its excavations of the politics of late 19th-century France.

All this is anathema to our age, unfortunately, from the idea of authors writing about people they are culturally removed from to the whole idea of putting something into print that might shock or offend. As a result, the novel as a form is often said to be dying, which is true in some senses, but not for the reasons usually given. If the novel can no longer expand itself and go to new places, becoming nothing more than a place for people to relate their ‘authentic experience’, then of course the form will begin to die.

In the epilogue to Living and Dying with Marcel Proust, there is a beautiful story about a film project, initiated in 1993 and still going today, which involves filming different people reading two pages of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu to camera. It has featured the actor Kevin Kline, an inmate in a French prison, a Lebanese artist, a Slovenian Proust translator, a distant cousin of Proust and a shepherd living so high in the Cévennes, the camera crew had to walk on foot for an hour and a half to reach him. It is a fine example of the universality of Proust and how inventiveness and risk-taking need not be a block to reaching a large audience across time and space.

Prendergast’s Living and Dying is, among other things, a primer on why it is time to either discover or re-discover the charms of one of the greatest novels ever written, not just because there is much in it that informs our times, but because it also shines a light on what the literature of the 21st century is missing.

Nick Tyrone is a journalist, author and think-tanker. His latest novel, The Patient, is out now.

Living and Dying with Marcel Proust, by Christopher Prendergast, is published by Europa Compass. (Order this book here.).

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.