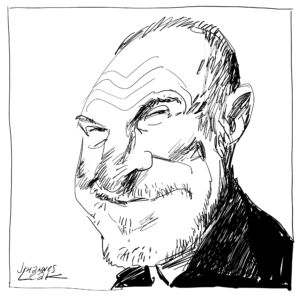

Barry Cryer: an incomparable comic

His timeless, immortal comedy stayed vital to the last.

Barry Cryer, who has died aged 86, was notoriously fond of a parrot joke. The foul-mouthed parrot who finally mends his ways after spending five minutes in the freezer, and comes out ashen-beaked, wanting to know what the chicken had done. The parrot rescued by a kindly lady from the brothel, which is then rude to her daughters but on suspiciously familiar terms with her husband. The parrot who gives away the cruise magician’s tricks, until the ship sinks and the parrot has to admit defeat: ‘All right, I give up – what have you done with the ship?’

Barry was fond of quoting EB White on comedy: ‘Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You may understand it better but the frog dies in the process.’ (Or as we say in the business, the frog has a ‘weird gig’.)

However, at the risk of triggering such an autopsy on this sad but I hope not sombre occasion, it is telling that Barry was drawn to this genre. Parrot jokes, as Evelyn Waugh said of Wodehouse, take place in an idyllic world that can never stale. They are not topical. Nothing is being satirised or critiqued. They are timeless. And there is nothing like a parrot, squawking obscenities, to remind mankind of its essentially ridiculous existence, despite all our airs and affectations. A parrot is a jester in nature’s motley, and the original ventriloquist’s dummy – that innocent-faced conduit to our darkest, secret truths, and the key to all comedy, and misrule generally. Parrots have as much in common with Lear’s Fool and the Theatre of the Absurd as they do with Private Eye.

Beyond the endless, tiresome debate in comedy about who should be the butt of your jokes, and the difference between punching down and punching up, Barry’s jokes didn’t punch down or punch up. They just went off, exploded, like a parrot in a microwave, and the feathers went everywhere.

Cryer’s career was vast. He bestrode postwar comedy like an enormous pair of beige slacks stepping gingerly over a sleeping Great Dane. His writing CV, even that sliver of it captured on his Wikipedia page, demonstrates a span and a range that is unlikely ever to be even remotely approached again. He wrote for Dave Allen, Stanley Baxter, Jack Benny, Rory Bremner, George Burns, Jasper Carrott, Tommy Cooper, Les Dawson, Dick Emery, Kenny Everett, Bruce Forsyth, David Frost, Bob Hope, Frankie Howerd, Richard Pryor, Spike Milligan, Mike Yarwood, the Two Ronnies, and Morecambe and Wise. As a golfer once said of a rival with a powerful drive, I can’t even point that far.

Yet he also survived meaningfully into the present moment, with extraordinary vitality to the last. Among the few names who can be safely mentioned in the same breath – Eric Sykes, Barry Took, Frank Muir and Denis Norden – none seem to have adapted as Cryer did, to have embraced comedy’s evolution, and to have had such an enormously warm, utterly human relationship with so many comedians young enough to be, as Groucho Marx once put it, his so-called niece.

But perhaps ahead even of the greatest writing resumé in comedy – and his mentoring and support for the next generation, and the next, and the next – he will be remembered most fondly for his contributions to what is probably the funniest radio show ever made. And when I say ‘probably’ I mean in the way that the Eiffel Tower is probably the most famous iron prong in France.

The show has evolved, nobly, through many sadly necessary iterations. But there are many of us for whom the golden-era I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue – Humphrey Lyttelton in the chair with Cryer, Willie Rushton, Graeme Garden and Tim Brooke-Taylor, and Iain Pattinson and Jon Naismith behind the scenes – was not simply the best thing on Radio Four, it was the best thing, of anything, ever. As Alfred Wainwright said of his beloved Haystacks in the Lake District, a man might forget a raging toothache listening to ISIHAC, and I would not be remotely surprised if it had prevented suicides, saved marriages, and perhaps even fathered a child or two, too.

Barry’s contributions, delivered in that incomparable, gurgling, bronchial and port-gargling baritone, as he announced the late arrivals at the Electricians Ball, or sang ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ to the tune of ‘Anarchy in the UK’, are of course immortal. But even more, perhaps, is his laugh. Simply the most generous laugh in showbusiness. It dissolved whatever is the radio equivalent of the fourth wall – the third ear? – more effectively than any sound I’ve heard before or since.

I made him laugh myself just a few times. The first, I remember, was at a BBC Christmas drinks thing in the Radio Theatre. It was a silly, off-the-cuff remark about the nature of sheep worrying – and I can still close my eyes and picture it and hear it, as it bubbled out of him like a spring. This was, for a comedian, like pulling the sword from the stone. One felt anointed. It was about 20 years ago now, and I have, frankly, been coasting ever since.

To die at 86 is no tragedy. To breast the tape with the laughter of your friends still ringing in your ears is a bloody triumph. But there is no escaping the fact that the hearth feels a little colder tonight, and the light fading in the West has lost a little of its reassuring golden hue. Where, I wonder, is that bloody parrot now, just when I need him most?

Simon Evans is a spiked columnist and stand-up comedian. He is currently on tour with his show, Work of the Devil. You can buy tickets here.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.