Long-read

David Amess and the terrorism amnesia industry

Why the elites are so desperate to avoid discussing radical Islam.

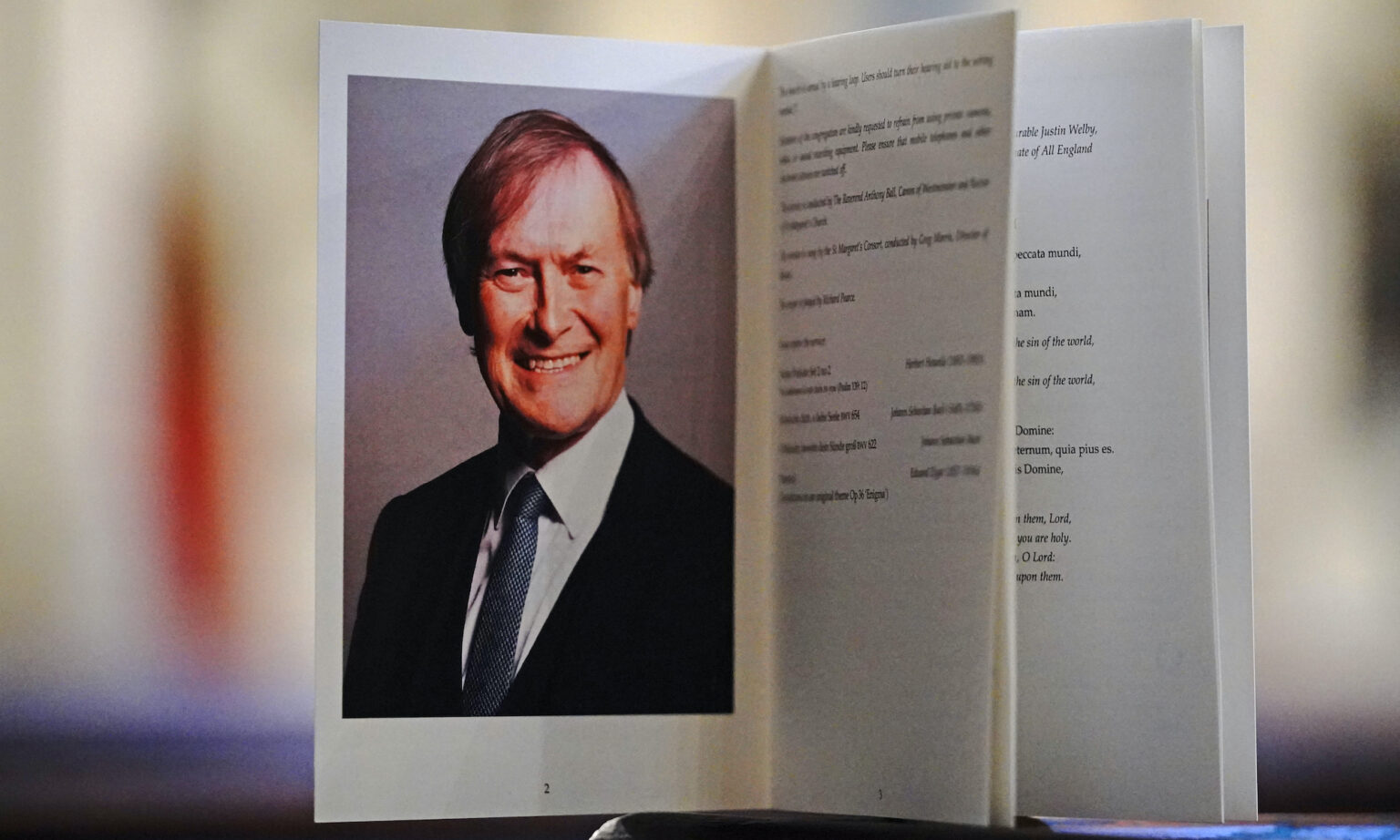

The killing of Sir David Amess is starting to slip from public consciousness. You can feel it. Just two weeks after the Conservative MP for Southend West was allegedly murdered in a suspected Islamist terror attack, it seems like this horror is fading from national memory. Yes, numerous tributes were paid. The media coverage was extensive. Parliament garlanded Amess with touching tributes. And, in his memory, Southend will be granted city status, something he campaigned for throughout his political career. So there has not been nothing. Of course not. And yet it seems undeniable now that this atrocity is not being accorded the political and historic moment it surely deserves.

We seem to be witnessing the cranking into action of the Islamist terror amnesia industry. This is the means through which, subtly and sometimes imperceptibly, memorialisation of lives lost to suspected Islamist terror is discouraged. Where the politics is drained from such outrages and we are pressured to view them less as violent expressions of a particular ideology and more as sad, unpleasant events. As occasions for grief, not anger; for fleeting reflection, not societal interrogation. This happens after every suspected Islamist attack. The elite’s fear of what would happen if we had an honest, collective confrontation with the problem of radical Islam comes to outweigh everything else, even the act of remembering. Two weeks after Amess was killed, a horror now being investigated under the Terrorism Act and suspected of having an Islamist motivation, it’s happening again.

To get a sense of how intensely suspected Islamist attacks are depoliticised and even de-memorialised in comparison with other forms of ideological violence, compare and contrast the media elites’ response to the murder of another MP, Jo Cox, with their reaction to the killing of Amess. The killing of Cox in 2016 was institutionalised as an event of high political importance with extraordinary haste. Just days, and in some cases hours, after the Labour MP for Batley and Spen was murdered by far-right extremist Thomas Mair, the nation was encouraged to view this horror not only as a terrible tragedy but also as a violent representation of the warped ideologies of contemporary Britain. As the Guardian put it on the day Cox was killed, this was not just an ‘exceptionally heinous villainy’ – it was a bloody manifestation of the ‘brutal cynicism’ of right-wing politics and its ‘divisive hate-mongering’.

In stark contrast, we are now expressly instructed not to read politics into the Amess killing. At least not yet. So the Guardian’s sister paper, the Observer, counsels against the drawing of conclusions from the Amess atrocity on the basis that we just don’t know enough about it yet. Two days after Amess’s death, on 17 October, the Observer warned against over-politicised interpretations of this violent act. ‘We know little about the circumstances surrounding the fatal attack on Amess’, the paper said, when in fact, by that stage, we knew far more about this killing than we did about the killing of Cox when the Guardian transformed it, hours after it occurred, into proof of our ‘slide from civilisation into barbarism’. Now the Observer reprimands those who ‘seek to deploy’ the ‘scant details’ of the Amess killing ‘in service of their political agendas’, especially the agenda of talking about the problem of radical Islam. ‘[To] politicise this tragedy in such a way is abhorrent’, it says.

This is extraordinary. Here we have the media conscience of the liberal elite – the Guardian Media Group – inciting the politicisation of one fatal assault on an MP and forbidding the politicisation of another fatal assault on an MP. Demanding a focus on far-right extremism following the killing of Cox and denouncing any focus on Islamist extremism following the killing of Amess. Five years ago the liberal media openly said the killing of Cox must not only be viewed as a dreadful act; it must also be politicised. Now the same media elite describes as ‘abhorrent’ any effort to treat the Amess killing as a political event. The Observer’s ‘scant details’ line is especially striking. Imagine if the Telegraph or the Spectator had fumed against the politicisation of the Cox killing on the basis that Mair’s yelling of the phrase ‘Britain first’ was a ‘scant detail’ undeserving of meaningful political attention. There would have been fury. And yet the Observer can say this kind of thing about the Amess killing and it causes no controversy whatsoever.

It isn’t only the Guardian / Observer. Across the board, in both the political class and the media elites, the difference between the treatment of the Cox horror and the Amess horror has been palpable. It demands scrutiny. Of course, the murder of Cox came to be bound up with the elites’ dread over the EU referendum. Cox was killed just one week before the nation voted on whether we should stay in or leave the EU. A political and media class panicked by the prospect that the electorate would opt for Leave, and unnerved by the very holding of a referendum on a matter of such high constitutional importance, came to view the killing of Cox as symbolic of the moral and political turpitude of the Leave campaign and its backers among the oiks. They saw in Mair’s grotesque act a distillation of the unwieldy passions of the broader Leave-backing multitude.

Collective blame for the Cox killing was dealt out almost immediately. This horror was down to politics, and in particular to the Leave campaign, we were told. Polly Toynbee, on the day Cox was killed, claimed the ‘referendum campaign’ had made the air ‘corrosive’. Leavers had created a ‘noxious brew’, she said, ‘with dangerous anti-politics and anti-MP stereotypes’. Deploying an alarming insect-like metaphor, Toynbee said the leaders of the Leave movement had ‘lifted several stones’ and let out a ‘rude, crude, Nazi-style extremism’. Alex Massie argued just one hour after Cox was killed that her killer – of whom we knew virtually nothing at that point – was probably motivated by the Brexit atmosphere. ‘When you encourage rage you cannot then feign surprise when people become enraged’, he said. Across the chattering class, the alleged political source of the Cox horror was sought out immediately, initially as part of the Remainer elites’ desperate effort to tar Leave with the brush of terrorism.

But the hyper-politicisation of the Cox killing was not only an act of extreme opportunism by members of an elite baffled that we were holding a referendum on the EU. It was also motivated by a desire to highlight the problem of right-wing terrorism. Don’t look away from this ideological scourge, we were told. When Mair was convicted in November 2016, there was an explosion of commentary demanding attention be paid to right-wing extremism. ‘The impact of extreme, far-right crime should not be ignored’, said one writer. ‘A far-right terrorist murdered Jo Cox – so when is the Cobra meeting?’, asked the New Statesman, the clear implication being that officialdom focuses too much on Islamist terror and not enough on right-wing terror. The Independent complained that ‘the focus on Muslim-related extremism [has] overlooked the growing threat from the far right’. Far-right extremists, the Independent reported, completely ridiculously, are ‘much more lethal’ than Islamic extremists.

So the politicisation of the Cox killing had two components. First, it was an exploitation of an awful event in the service of Remainer propaganda in the final week of the EU referendum. And secondly, it was about saying this is political. This kind of violence is an ideological menace that we should not shy away from talking about. Rather, the commentariat insisted, we should actively encourage the population to discuss these twisted ideologies and get angry about them. As that Toynbee piece said, ‘It’s wrong to view the killing of Jo Cox in isolation’. Rather, it sprung from, or at least manifested, a far larger ‘chilling culture war’. The Cox killing was super-politicised, marshalled to the service of a narrative about Brexit-related political malaise and about the importance of confronting far-right terror.

The Amess killing has been followed by almost precisely the opposite urges. The instinct, everywhere, has been to depoliticise. Or rather to politicise it but in such a way that attention is taken off the problem of radical Islam and zoned into other, entirely unrelated areas of policy. The impulse has been to defuse, to diminish. To drain away strong political and emotional feelings about the suspected motivating ideology of the attack, rather than to intensify such feelings, as happened when Cox was killed. It would be ‘abhorrent’, as the Observer says, to politicise a tragedy like this in order to talk about the problem of Islamism. In short, this horror should be seen in isolation. It is awful and sad and deserving of our tears, of course; but apparently it doesn’t require meaningful ideological or social interrogation.

One of the key arguments made by the media defusers of the Amess horror is that we just don’t know enough yet to have an informed discussion. Everything is ‘scant’. This isn’t true. Of course, no discussion should be had about who is responsible for this killing. The individual who is being held under the Terrorism Act is innocent until proven guilty. Justice must be allowed to take its course. But we do know a lot about the suspicions of officialdom in relation to this violent act. As Private Eye summarises it, ‘Less than an hour and a half after the Conservative MP Sir David Amess was stabbed to death just after noon on 15 October, Essex police announced that the investigation was being led by anti-terrorism officers’. By 7.30pm that evening, they were exploring a ‘potential motivation linked to Islamist extremism’. Then, on 21 October, six days after the killing, it was confirmed that the suspect would face charges of murder with ‘a terrorist connection, namely that it had both religious and ideological motivations’ and also ‘the preparation of terrorist acts’. And yet despite all this, as Private Eye puts it, much of the press has ‘decided [that] Amess’s death was about something else entirely’.

The defusing of the suspected Islamist element of the attack on Amess, of the fact that this is now being treated as a possible act of Islamist terrorism, has taken two forms. First, we have witnessed what we might call the phoney politicisation of the Amess killing – the transformation of it into a political event, yes, but one which apparently has little to do with the problem of radical Islam. Across the establishment, the Amess attack has been firmly removed from the sphere of ‘Islamist terrorism’ and placed instead in the sphere of ‘online abuse’. MPs and the media have relentlessly focused on the problem of mean tweets, online anonymity and verbal abuse aimed at MPs, even though it is not at all clear that any of these contemporary problems played a role in the targeting of Amess. This partisan, cynical politicisation of the Amess killing to the end of problematising online culture is best understood as yet another form of de-politicisation – a political means of distracting attention from what is suspected to be the real political problem behind an attack like this: radical Islam.

And secondly, there has been the marshalling of the ‘Islamophobia’ problem. This happens after every act of suspected of Islamist terrorism, without fail. We are told that too much anger or even just frank public discussion about the problem of radical Islam could have destabilising and even violent consequences. It is a form of emotional blackmail.

Curb your passions and political concerns about this ideological menace or else we will witness an unravelling of social bonds and an explosion in hate – that is the message we receive from on high, every single time. After the Manchester Arena bombing (‘Don’t look back in anger’). After the London Bridge attack, when football fans who marched to raise awareness of the Islamist problem were furiously denounced as dangerous and Islamophobic. Even after the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris, when we were warned by one observer that ‘Islamophobes [will seize] this atrocity to advance their hatred’. Apparently, the aftermath of that massacre represented a ‘dangerous moment’, not because supporters of freedom of speech were under violent attack but because ‘anti-Muslim prejudice is rampant in Europe’. This is the script of the elites after every Islamist atrocity: Be careful how you talk about it or you might help to unleash violent racism. Neuter your political anger or you risk igniting a pogrom against Muslims.

We have seen this deeply cynical, censorious and distrustful narrative being rolled out once again following the killing of Amess. ‘British Muslims prepare for surge in Islamophobia following David Amess murder’, says one headline. ‘Terrorist attacks often spark fresh waves of Islamophobia’, the Huffington Post warns. The Muslim Council of Britain has drawn attention to ‘the real apprehension within British Muslim communities… at the prospect of an increase in hate-crime offences’. This view of the post-terror moment as a uniquely volatile time, one in which violence could blow up at any moment, is intimately linked with the Observer’s insistence that it would be ‘abhorrent’ to politicise Amess’s killing to the end of discussing the Islamist problem. It all acts from a censorious instinct to quell public concern about radical Islam, to dampen the anger people might understandably feel about this violent ideology that has killed scores of our fellow citizens in recent years. The spectre of ‘Islamophobia’ is marshalled as a means of thwarting democratic discussion and even any kind of firm memorialising of acts of suspected Islamist terror.

We now have a perverse situation where, thanks to the phoney politicisation of the Amess killing as a problem of online culture, and as a result of the raising once again of the ‘Islamophobia’ problem, there has been more discussion about right-wing violence than there has been about radical Islam since Amess was killed. The liberal media chastise too keen a focus on the Islamist issue while flagging up the potential for a right-wing backlash against the Muslim community. For two weeks now, we have been instructed, time and again, to think less about the problem of radical Islam and more about the alleged scourge of rude online trolls and about a possibly emerging anti-Muslim mob. It has all been a classic example of the Islamist terrorism amnesia industry getting to work: ‘Don’t focus on the ideology that is suspected to be behind this attack – focus on anything else instead.’

The false equivalence that is made between Islamist terror and far-right extremism needs to be called out. More pointedly, the perverse equivalence that is made, at least in terms of the size of liberal media commentary, between acts of Islamist violence and their potentially Islamophobic aftermath, between the barbarism of something like the Manchester Arena bombing and the allegedly destabilising consequences of talking about such a horror too frankly and passionately, needs to be firmly challenged. The Independent was entirely wrong to report, following the conviction of Mair in 2016, that far-right extremism is ‘much more lethal’ than Islamic extremism. More than 90 people have been killed in the UK by Islamic extremists over the past 16 years; only three people have been killed by far-right extremists. The elites’ pathological obsession with downplaying the Islamist scourge – with continually deflating the problem, distracting from the problem, defusing the problem – is an Orwellian strategy designed to gaslight the public into believing that it is us who are hateful for worrying about the Islamist ideology.

What lies behind the Islamist terror amnesia industry? Why do the new elites take this approach of whataboutery and emotional blackmail in the aftermath of suspected Islamist terror attacks – with so much success that many people will have genuine difficulty recalling something like the Islamist stabbing to death of three gay men in Reading last year or the total number of victims of the Manchester Arena bombing? It is a product of their fundamental fear of the public and of democracy. It is their view of us as a low-information, potentially violent throng that has led them to believe we cannot be trusted to discuss something as contentious as the Islamist ideology. At times it seems they fear us and our response to terrorism more than they fear terrorism itself – that is how staggeringly out of touch with the public they have become. Moral cowardice and disdain for democracy lie behind their cultivation of the Islamist amnesia industry.

At root, they want to protect their ideology of multiculturalism from serious democratic interrogation. And thus they must quell, with distraction and dire warnings, any kind of public scrutiny of how divided and tense Britain has become under this system of cultural and ethnic separatism, to such an extent that religious violence is now a fairly regular occurrence in our society. Shush. Forget about it. Don’t look back in anger.

Brendan O’Neill is spiked’s chief political writer and host of the spiked podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show. Subscribe to the podcast here. And find Brendan on Instagram: @burntoakboy

Pictures by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.