The UK is squandering its post-Brexit future

Poor productivity, low R&D spending and a lack of appetite for global trade are holding us back.

The UK is squandering its Brexit dividend. At this rate, we will struggle to make the most of the opportunities afforded by the 21st century.

For those of us who championed Brexit, leaving the EU offered a unique opportunity for the UK to look beyond Europe, particularly towards the Commonwealth. But calls for closer ties with Australia, Canada and New Zealand – with whom we already share a head of state – have been largely ignored by our government.

Although the UK has made excellent progress signing trade deals with countries across the world, our trade deal with Australia was largely a fudge. This was thanks in part to fears that a more comprehensive deal might have resulted in even tougher controls on the Irish sea border. A rejuvenated Commonwealth or a so-called CANZUK alliance – that is, an alliance between Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK – could be a game changer for Britain. But our government is still too mired in arguments with Brussels over the Irish border to begin to look outwards.

There are some causes for optimism. The UK remains the world’s fifth largest economy. It is still one of the world’s major geopolitical players and one of only five permanent UN security council members. It hosts one of the world’s two major financial centres. And it is only one of two countries in the premier league of higher education (the other being the US). But all of these great assets become irrelevant if complacency sets in.

Take higher education. As the past century has shown, universities are the ideal institutions for incubating tomorrow’s growth technologies. There is a good reason why Silicon Valley is so close to Stanford, Berkeley and Caltech. While universities in Asia are clearly focused on economic revolution, British universities, like many of their US counterparts, seem increasingly focused on social revolution.

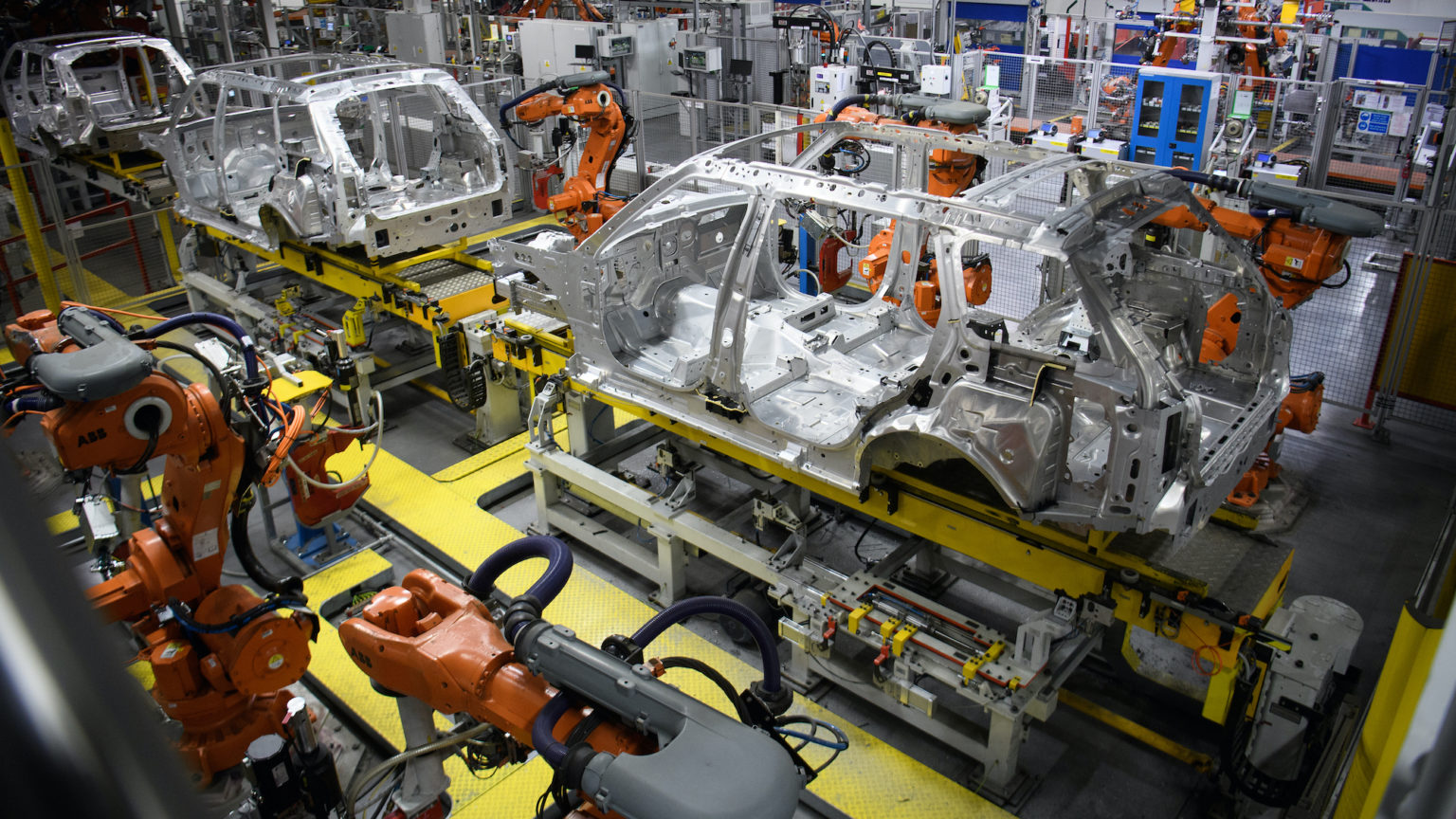

Even when good ideas do come out of our university sector, we currently lack the manufacturing capacity to capitalise on them. As Dr Clive Hickman, CEO of the Manufacturing Technology Centre, has pointed out, while the UK is undoubtedly a ‘world leader in scientific research’, the majority of our innovations are manufactured overseas. As a result, ‘the long-term orders balance on manufactured goods stands at minus 34 per cent’. According to Hickman, our government could do much more to fund ‘translational research’ – that is, ‘taking the best ideas conceived within British academia, and converting them into products and processes’.

The UK has the potential to be a leader in everything from 3D printing to quantum computing. But without the political will and funding, these innovative new sectors will largely be based elsewhere.

Meanwhile, recent isolated successes – such as London’s booming fintech sector – cannot mask the UK economy’s poor productivity and low investment in research and development. According to the LSE’s Ethan Ilzetzki, the UK’s output per hour has underperformed the rest of the G7 for decades. A report by the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts from last May found that the UK’s investment in R&D is also low in comparison to other advanced countries. As a percentage of GDP, the UK’s R&D spending is much closer to the likes of Italy and Spain than Germany. Fixing this must be a priority for the government.

One source of optimism here is the establishment of ARIA (the Advanced Research and Invention Agency) – Britain’s answer to the US’s DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency). But the sums involved (just £800million so far) are currently too small to pack a real punch. If tomorrow’s world belongs to the producers of growth technologies, the UK should be investing now to benefit future generations.

Existing government initiatives like freeports might be eye-catching, but they alone are not enough to secure Britain’s economic future. There are plenty of opportunities for rejuvenation. But until we can make the most of the Brexit dividend, close the productivity gap and build on our advantage in higher education, the UK will continue to coast.

Jonathan Saxty is a businessman and commentator.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.