Why heretics need to be heard

If we silence those who challenge groupthink, who knows what insights we are missing out on.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Social-media platforms are increasingly acting as moral censors and banning those whose views either contradict official policy or simply offend people.

Facebook has barred those it calls ‘dangerous individuals’, including Milo Yiannopoulous, Alex Jones, Laura Loomer and Louis Farrakhan. Katie Hopkins had 1.1million followers on Twitter by the time her account was permanently removed. David Icke’s channel was recently deleted from YouTube because he was spreading conspiracy theories about coronavirus.

It is often talked of as a self-evident good that people should be banned from social media for views which are odious, heretical or offensive. But in truth, it takes us down a dangerous path.

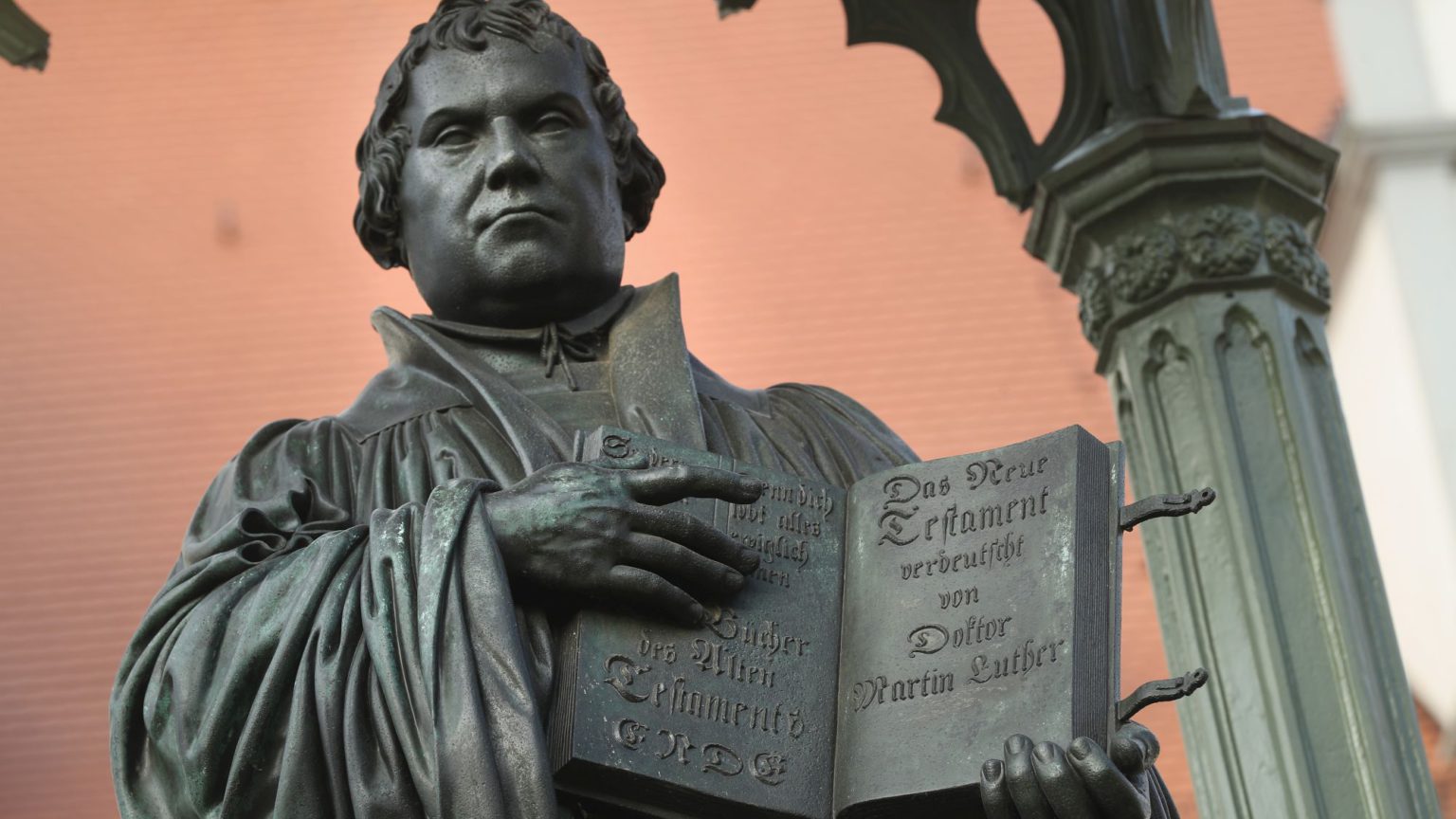

Let’s look back in history to see what happened to some whose opinions were considered detestable or heretical at the time. Martin Luther (1483-1546) was a German professor of theology, a priest and an Augustinian monk. In 1517, he wrote to his bishop, protesting against the sale of indulgences. His letter became known as his 95 theses.

At first, Luther had no intention of confronting the Catholic Church. He had merely set out some scholarly objections to some of its dubious practices. He wanted to reform the church rather than break with it. Many of his complaints were perfectly valid and did not relate to fundamental doctrine. The Catholic Church could have reviewed the grievances and reformed. Instead, it reacted by issuing excommunications and anathemas. If the church’s leaders had listened to his criticisms rather than rejecting them outright, it is possible that the Reformation could have been avoided and countless lives may have been spared from the religious wars which followed.

Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice (1845-1927), the 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, was a distinguished British statesman. He had served as the fifth governor-general of Canada, Viceroy of India, secretary of state for war, and secretary of state for foreign affairs. He was a pillar of the British aristocracy.

By November 1917, the First World War had raged for three savage years with millions dead. Lansdowne, whose son had been killed in action, became convinced that the war was a threat to civilisation itself and that the total destruction of Germany was not a worthwhile objective.

Impelled by his conscience, he circulated a paper to the government, in which he called for an end to the bloodshed and a negotiated peace with Germany. His proposal was summarily rejected by his colleagues. He invited the editor of The Times, Geoffrey Dawson, to his house and asked him to publish a letter expounding his case. Dawson was appalled and refused. Lansdowne then offered the letter to the Daily Telegraph, which published it on 29 November 1917:

‘We are not going to lose this war, but its prolongation will spell ruin for the civilised world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it… We do not desire the annihilation of Germany as a great power… We do not seek to impose upon her people any form of government other than that of their own choice… We have no desire to deny Germany her place among the great commercial communities of the world.’

Condemnation was swift and almost universal. Lansdowne became a pariah who was shunned and vilified by politicians, commentators and military leaders. His letter was condemned as a ‘deed of shame’. It was completely at odds with popular opinion which wanted nothing less than the annihilation of Germany. He was shunned, his career was over, and he was seen by many as a traitor.

Most likely he was right. His views should have been considered. If peace could have been negotiated with Germany, countless lives would have been saved. Furthermore the onerous reparations forced on Germany with the Treaty of Versailles would have been avoided. Many historians believe that the terms of this treaty laid the seeds for the rise of Hitler and the horrors of the Second World War.

A parallel story occurred half a century later. Konrad Kellen (1913-2007) was a German Jew who studied law before emigrating to the USA in 1935. He became an intelligence officer working for the US army and later for the RAND Corporation, an influential think-tank. In the 1960s, he studied interviews with hundreds of captured Vietcong fighters in order to interpret the morale and intentions of North Vietnam. Conventional wisdom in the Pentagon was that the morale of the Vietcong forces was low and that additional US forces and bombing would shortly bring about Vietcong collapse.

Kellen’s painstaking analysis led him to conclude that, contrary to prevailing assessments, enemy morale was high and the war was not winnable. In 1965, he and others wrote an open letter to the US government urging the withdrawal of troops. But his arguments were disregarded by the US administration. Kellen’s views were seen as disloyal, misguided and wrong. With hindsight we can see that Kellen was right and many lives would have been saved if his approach had been adopted.

Nobody would claim that the opinions of Katie Hopkins or Milo Yiannopoulous are as profound or as valid as Luther’s, Lansdowne’s or Kellen’s. But similar principles are nonetheless at play. As countless whistle-blowers have found, those whose views challenge current policies and groupthink are often rejected and silenced.

The Catholic Church and the British and the US governments did not listen to controversial views which confronted their assumptions. The consequences were devastating. We should not make a similar mistake by silencing those whose views challenge our own orthodoxies. We should allow a platform for contrarian thinkers – especially for those who annoy us.

Free speech should be indivisible. If you ban the likes of David Icke for being daft and Katie Hopkins for being offensive, you will sooner or later ban a present-day Luther, Lansdowne or Kellen — and they really do need to be heard.

Paul Sloane is an author, blogger and speaker.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.