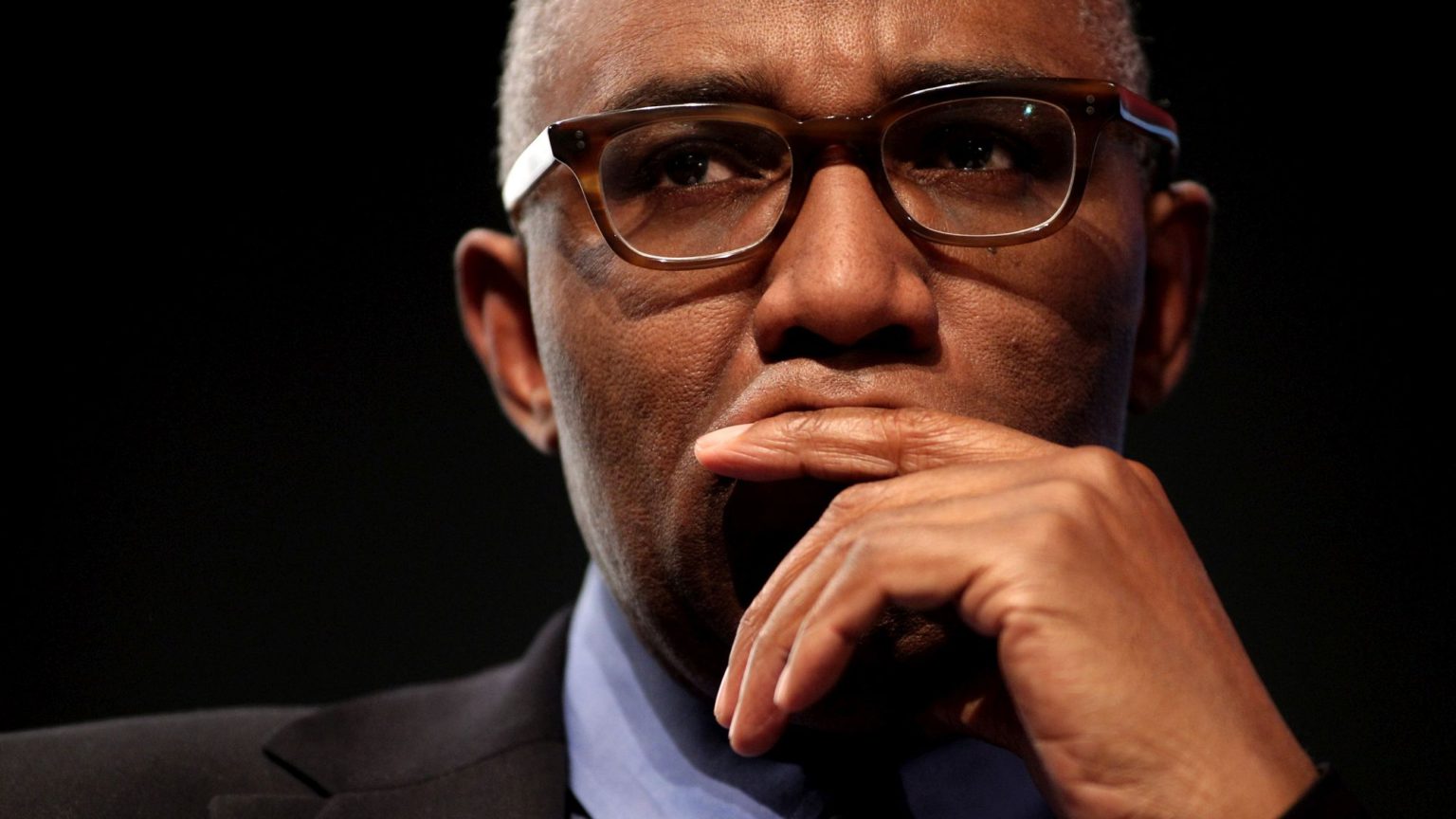

Trevor Phillips: a bad black man

The identitarian lobby hates Phillips because he rejects the cult of victimhood.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Why does the identity-politics set hate Trevor Phillips so much? Their loathing is palpable. They’ve hounded him out of the Labour Party, from which he was recently suspended on trumped-up charges of ‘Islamophobia’. They’re currently trying to get him thrown off the inquiry into why coronavirus has had a disproportionate impact on black and ethnic-minority communities. And they speak about him in the most demeaning and racialised terms. Kehinde Andrews, a Guardian contributor and academic, calls him a ‘modern-day Uncle Tom’ and accuses him of ‘coonery’. ‘Coon’, of course, is a vile racist word to describe a black person who exists merely to entertain white folks.

These intemperate, racialised assaults on a man who was the first black president of the National Union of Students, is a former chairman of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, and has a long track record of campaigning for racial equality, capture a dark irony at the heart of identity politics. This movement presents itself as anti-racist, but it is nothing of the sort. On the contrary, its racial fatalism, its treatment of every individual as little more than a racial creature shaped by the forces of history or the prejudices of the present, means it often crosses the line into something very like racism itself. This is why Trevor Phillips can be denounced as a ‘coon’ who holds views black people are apparently not meant to hold – because the identitarian set views blacks, and others, as monolithic groups who must all think and behave in the same way. And woe betide any black who deviates from the racial script.

Trevor Phillips, in essence, is a bad black man. Most identitarians don’t go as far as Andrews in accusing him of ‘coonery’, but they push a similar idea: that Phillips is little more than a puppet of the system, a political plaything of white folks. In an open letter criticising Public Health England for appointing Phillips to the inquiry into Covid’s impact on black and ethnic-minority communities, 100 black women from the worlds of media, law, health, education and publishing damn Phillips on the basis that he holds views that respectable black community groups disapprove of. He is most ‘famously known by many BAME community groups’, they say, for having a ‘recent history of discarding the very real issues and consequences of structural racism in the UK’. That is, he doesn’t share the view of these professional black people, these good black people, that structural racism remains endemic in Britain.

Strikingly, the letter-writers’ key piece of evidence against Phillips’ inclusion in the Covid inquiry is that he once said it is legitimate to hold minority communities responsible for some of the problems they face. They quote from his report, Race and Faith: The Deafening Silence, in which he lamented that ‘any attempt to ask whether aspects of minority disadvantage may be self-inflicted is denounced as “blaming the victim”‘. Instead, we are expected to say that every problem faced by minority communities is ‘all about white racism’. This, Phillips says, is a ‘dangerously misguided view’. In flagging up this quote in particular, the letter-writers make clear that their key problem with Phillips is that he bristles at the cult of victimhood that says every misfortune faced by minorities is the fault of others, and he believes things might be rather more complicated than that.

If anything, it is precisely views such as these that make Mr Phillips well-suited to the coronavirus inquiry. The juvenile treatment of Covid’s impact on minority communities as an issue of ‘racial injustice’ – in Sadiq Khan’s words – risks turning a complex health and social problem into a straightforward ‘woke’ case of black people being neglected by white people. And yet, as Rakib Ehsan has pointed out on spiked, alongside such socio-economic issues as living conditions and work practices, both of which may exacerbate Covid-19’s spread among minority groups, there may also be a problem with certain ‘lifestyle’ factors, such as diet and a corresponding higher prevalence of diabetes and heart disease. An inquirer who is willing to ask such questions, who thinks ethnic-minority groups are not mere victims to whom things are done by bad outsiders, is exactly what we need if we are to understand Covid’s complex impact on certain communities.

And yet the intolerant rage against Phillips’ inclusion in the inquiry continues. Sayeeda Warsi, writing in the Guardian, says ‘BAME groups’ have little ‘trust and confidence’ in him. A letter signed by ethnic-minority doctors calls on Public Health England to ‘withdraw the participation of Mr Phillips’. The Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), which never misses an opportunity to witch-hunt wrongthinkers, says Phillips must be dumped from the inquiry because he has a ‘consistent record in pushing the divisive narrative of Muslims being apart from the rest of British society’.

Here, again, we can glimpse the ideological component to this neo-McCarthyite effort to have Phillips cast out of public life. The MCB is opposed to Mr Phillips, not because he holds any prejudiced views, but because he has dared to criticise certain practices in sections of the Muslim community – in particular patriarchal and misogynistic practices – and because he has taken to task the fragmentary nature of the ideology of multiculturalism. Phillips’ concern is that the contemporary cult of diversity has its ‘discontents’ and could cause Britain to ‘sleepwalk towards segregation’. Phillips is being demonised and censured for holding perfectly legitimate views – views that may not win the approval of the arrogantly self-appointed spokespeople for Muslims, black people and others, but which nonetheless have great traction with many people around the country, including people from ethnic-minority backgrounds who do not consider themselves perma-victims.

The ridiculous branding of Phillips as a racist or an ‘Islamophobe’ reveals the sly disguise political censorship wears these days. Criticise the more divisive aspects of multiculturalism and you’re a racist. Say anything less than effusively positive about Islam or Muslim-community practices and you’re an ‘Islamophobe’. These words are increasingly used to circumscribe public debate, to shame those who deviate from the orthodoxies of the multiculturalist establishment, and to expel thoughtcriminals from the public realm. The once noble endeavour of anti-racism has been twisted to the narrow, cynical end of censuring and shaming those who question the outlook of the new elites. This is bad for open debate, and bad for anti-racism.

Phillips is hated because his arguments threaten to upend the privileged position enjoyed by the self-styled representatives of minority groups. In recent decades, an almost neocolonial politics of community has emerged, in which we are no longer seen as equal citizens of the nation of Britain but as fragmented communities, as ethnic and religious groups, who all require our own priestly spokespeople to represent us to the powers-that-be. At the top of this neocolonial pile stand the community spokespeople, never elected, who appeal for economic, social and moral resources from the state on the basis that ‘my community’ is more put-upon than other communities. The result is a competition of grievance, an ugly clash of competing claims to victimhood, in which each master of a community is implicitly encouraged to exaggerate his or her community’s predicament and flag up their apparent weakness and suffering. This is incredibly damaging to social relations in the UK and to any sense of autonomy within communities themselves.

And then along comes someone like Phillips, and others too, arguing that we aren’t all victims, that not every problem is inflicted on us by others, and that perhaps a sense of responsibility is more conducive to the good life than a ceaseless culture of complaint. And the new elites loathe him for it. Because they know that this more positive worldview is a potential wrecking ball to the grievance industry they helped to build and which they have benefited from for so long. The bad black man must be silenced.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked and host of the spiked podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show. Subscribe to the podcast here. And find Brendan on Instagram: @burntoakboy

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.