Long-read

Labour won’t transform our economy

Both Corbyn’s fans and his critics forget that state intervention is a normal part of capitalism.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘Ambitious’ and ‘radical’ were two of the friendlier assessments of the Labour Party’s manifesto plans.

Ambitious? Labour is certainly ambitious electorally. Labour’s manifesto is published with the desperate hope that its green spending plans, an end to student tuition fees, providing student maintenance grants and the offer of free broadband for all can be so appealing to voters that it will camouflage the party’s rejection of the Brexit vote – the very issue that precipitated this election.

But ambitious in transforming society for the better? Definitely not. This is because it is not ‘radical’, either – not in the sense of getting to the roots of society’s or the economy’s troubles. Bashing billionaires might make the Labour team feel they are on the side of ‘the many’, but the plans are no substitute for a necessary programme of economic renewal that could genuinely aid the masses.

The overexcited reaction from both supporters and opponents rests on the long-established – though entirely false – presumption that the state and the market are opposites. Extending what the state does in the economy has come to be regarded as an attack on capitalism. More state is thought to equal less market capitalism, and vice versa. This misconception underpins the sort of criticism of Labour’s manifesto editorialised by the pro-market Financial Times. The FT calls it ‘a blueprint for socialism in one country’. The ‘vast expansion of the state’ represents a ‘recipe for terminal economic decline’, it says.

In reality, the state and the market have operated in tandem ever since the earliest days of capitalism. The modern state is an indispensable institution of capital which carries out things that are required for the economy to function. This includes legislation to stabilise competitive practices, external defence, welfare and law and order, as well as subsidising critical sectors and infrastructure.

The state intervenes to establish and maintain the necessary conditions for all business activity. It always has done and it always will do as long as production is conducted only for exchange, thereby only meeting society’s needs indirectly. The state apparatus acts where individual business-owners won’t, or can’t, because the profit motive is not compatible with providing the broader requirements of the capitalist system. In consequence, the more developed capitalism has become, the more areas the state engages in that serve business overall.

The state and the market have operated in tandem ever since the earliest days of capitalism

Illustrative of this is the historical record for UK state expenditure, which is a fair proxy for the level of government economic intervention. Two features jump out from the history. First, the steady rise in spending since the middle of the 17th century, punctuated by upward leaps during the major wars: the Napoleonic wars, then the First and Second World Wars. Second, after the Second World War, unlike after the two previous wars, spending never fell away again by much. Post-1945 capitalism has been permanently dependent on state activities. In Britain, spending relative to national output has fluctuated during the past 70 years in the range between 35 per cent and 48 per cent.

Other developed-country governments spend similarly. Latest reported levels of state spending include the ‘free market’ US at 38 per cent – the same as Britain – Germany at 44 per cent and Sweden at 49 per cent. This is why elsewhere in the same edition of the FT that condemned the vast ‘socialist’ increase in the size of the state, it was let slip that it is ‘perfectly possible’ to run a successful economy with state spending amounting to 45 per cent of GDP: ‘Under a Labour government led by Mr Corbyn, spending would be lower than in France, about the same as Germany, and slightly higher than the Netherlands. All are successful capitalist economies.’

Anti-capitalist radicalism? While the Labour Party and its critics talk up the manifesto as something special and ‘radical’ in its expanded economic role for the state, Labour’s proposals are pretty much in line with common practice in developed economies. In fact, Labour’s proposals are more aligned to mainstream thinking today than the Tories’ more modest public-spending plans.

Just about every official Western market-supporting institution has recently been calling for governments to spend more to try to stimulate their anaemic economies. The very same day Jeremy Corbyn launched his manifesto in Birmingham, across the channel in Paris, Laurence Boone, the chief economist of the OECD, highlighted the urgency for ‘bold public investment’ to counter feeble growth. More than the ‘free market’ Conservative Party, the ‘socialist’ Labour Party was matching this call for boldness from the favourite policy forum of the advanced market economies.

Despite the long record of state-market interaction, the political instincts of the old left and the old right lead each side to respond dogmatically to the question of state intervention. Going back to the late 19th century, the roots of the interaction between the state and the market lay in the formal separation of political from economic power that distinguishes capitalism from earlier forms of production. In feudalism, political power derived from controlling the land that produced the foodstuffs and clothing materials. In slave-based production in classical Greece and Rome, slave owners constituted the class of political leaders. In those pre-capitalist societies, overlapping economic and political control relied on armed might to dominate the mass of people.

In contrast, under capitalism the state appears as a politically neutral institution, not taking sides between the main economic classes but representing the will of everyone in society. In pursuing the wider interest of capitalism, the state has often mediated between classes in pursuit of social tranquillity, as well as regulating the relations between particular capitalists. These actions reinforced the notion of state non-partisanship.

For instance, 19th-century workplace regulation, free elementary education, healthcare and welfare reforms all served the general interests of capitalist production. The benevolent appearance of many of these measures has, however, encouraged many socialists to behold the state as the vehicle for making changes within capitalism. In particular, they see the state as an impartial economic agent. The illusion that state intervention could restrain market forces and transform society became known as state socialism.

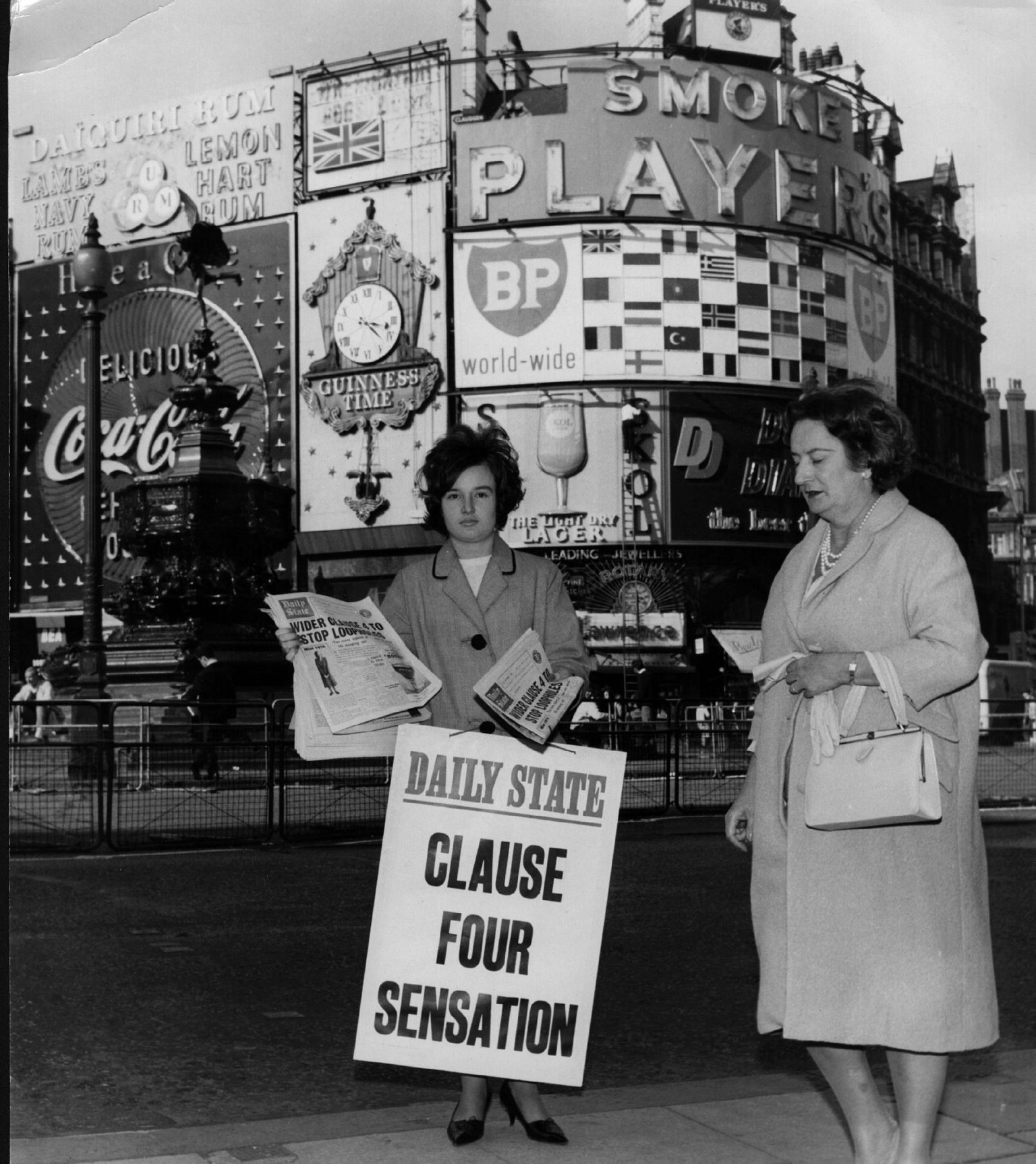

This attachment to the state has been the hallmark of all social-democratic parties of the 20th century up to the 1980s. It lingers on in the cliques and groupings that have inherited the old political labels. Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, as Labour Party left-wingers in the 1970s and 80s, were brought up on this state-socialist heritage. Even though the word ‘socialism’ only appears once in the current Labour manifesto – in a description of the NHS as ‘socialism in action’ – the focus on expanding the state is an echo of this previous left-wing tradition.

The scorn heaped on the Labour manifesto is another echo — of the political right’s defensiveness ever since the rise of working-class contestation in the 19th century. One expression of this was the emergence of so-called neoclassical economics from around the 1870s. Neoclassical economics – formulated by Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, Carl Menger and Alfred Marshall, among others – laid the basis for all mainstream economics of the 20th century, and much heterodox economics, too. Menger, for example, founded the neoliberal Austrian school of economics, while Marshall’s writings underpinned Keynesian economics. Neoclassical thinking watered down and debased their classical predecessors, like Adam Smith, David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill. They abandoned the classical focus on production at a time when the expanding industrial working class was grappling with capitalist iniquities.

Contrary to Labour’s manifesto assertion, there is no automatic connection between state ownership and democratic control

The subsequent intellectual inability of the political right and centre-right to provide a coherent promotion of capitalism led them to mimic the same misconceptions about the state that became increasingly popular among the left. The right also came to regard the state as potentially being in opposition to capitalism if government was led by the wrong types – that is, by socialists.

While the classical school of thinkers had opposed protectionism and other feudalist fetters on the workings of the market, it also understood the state’s activity as a normal part of the modern economy. Smith famously highlighted the state’s necessary role for law, order, defence from external attack and the provision of public goods and infrastructure. It was only the later, vulgar successors who created a discourse of ‘free market’ capitalism that mirrored the left’s illusions of the state as a potentially anti-capitalist reformer.

It is striking that Smith, as the proclaimed forefather of neoclassical economics, used the phrase ‘free market’ only once in all 785 pages of his opus The Wealth of Nations (in Book 4, Chapter 8, paragraph 26). And that was when he criticised the mercantilist prohibition of the export of English wool for driving down prices. Not many neoclassical thinkers, then or now, have that in mind when they eulogise the ‘free market’.

In fact, the left’s belief in the state as a potentially progressive body was given further assurance by the neoclassical right’s fetishisation of the ‘free market’ as good and state interference as bad. Today the inheritors of the mantle of ‘free market’ capitalism find themselves taking issue with the pale imitation of traditional state socialism represented by Corbyn and his group. The words of another 19th-century writer come to mind: ‘History repeats itself first as tragedy, then as farce.’ Two hollow vessels from left and right confront each other.

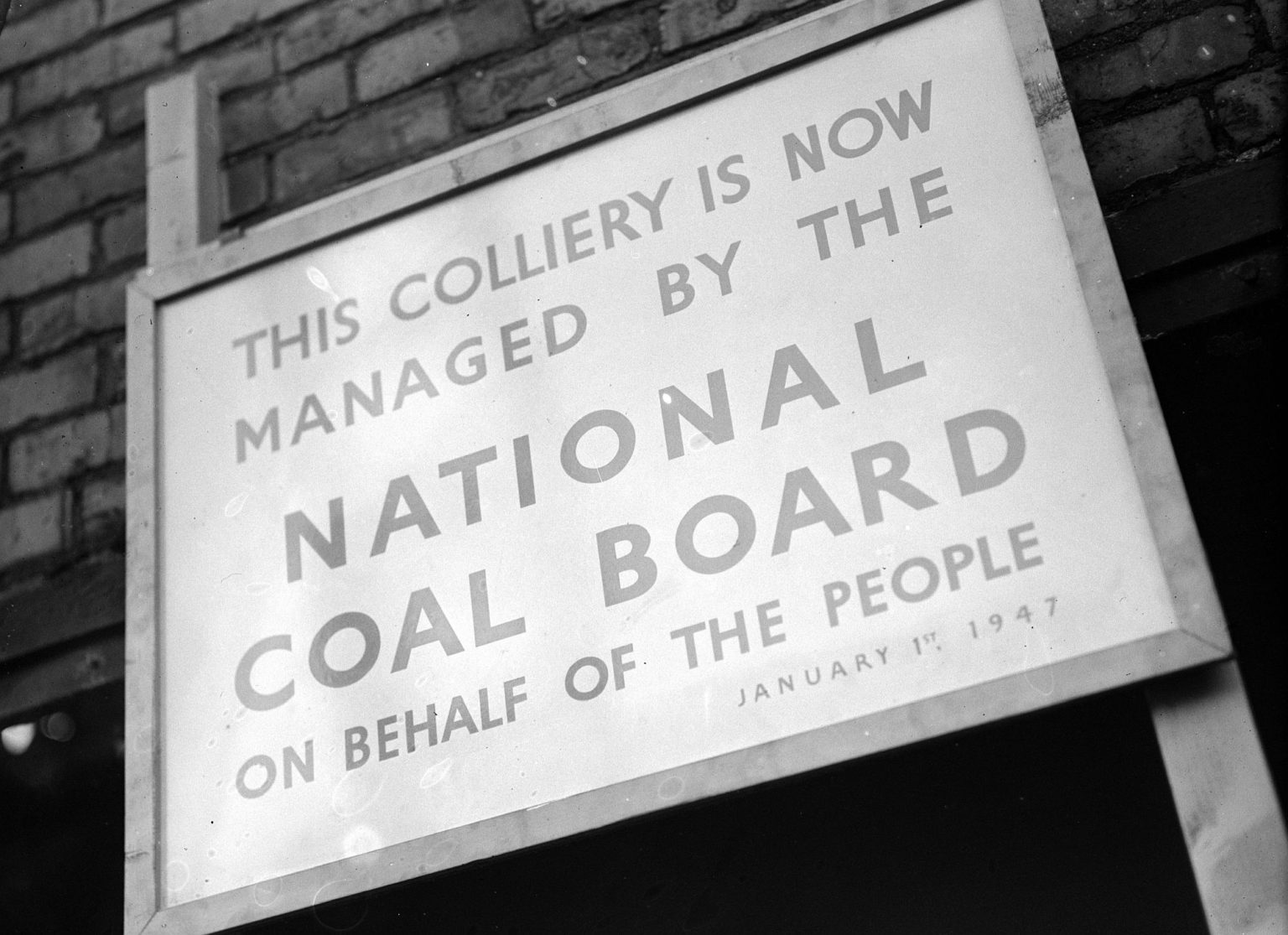

Take also Labour’s specific pledge to extend nationalisation. Such network services that everyone – people and businesses – need, also described as natural monopolies, have always been a common area of state intervention. Their supply often involves the building of physical networks – pipes, roads, rail tracks and cables – that would be wasteful and usually uneconomic to duplicate. For such utilities, competitive motivations are limited so the state usually takes on responsibility for provision.

State involvement in such matters takes various forms in different times and across different countries. Sometimes the state indirectly controls commercial businesses through regulatory oversight, enforced through dedicated government offices or commissions. Sometimes the state sets the goals and provides the funding while contracting out the provision to private companies. And sometimes state control is more direct through its own ownership by nationalisation. Nationalisation is therefore just one among several ways the state acts to ensure the continuation of productive activities.

In addition, nationalisation has been practised in some specific sectors where private business has failed to be profitable and where state subsidies have proved ineffective on their own. In Britain for instance, during the 1960s and 70s, four failing productive industries that were regarded as key to the country’s economic capabilities were nationalised wholly or in part: steel, shipbuilding, cars and aeroplanes.

Nationalisation plays a supportive role for capitalism. It only became a politicised word because of the limited ambitions of state socialism in regarding state intervention as the primary force for social transformation. In fact, direct state ownership actually existed long before the arrival of socialist parties. Public ownership of utilities goes back to the 19th century, with a sprinkling of even earlier instances.

As an alternative, the state-overseen private provision of utilities is not unusual either. It long preceded the so-called ‘free-market revolution’ of the 1980s, when we became familiar with another politicised term: ‘privatisation’. There were several instances of reversing nationalisation prior to Thatcher. After the Second World War, for example, the British steel industry was nationalised in 1951, mostly privatised again in 1953, and renationalised in 1967, before being privatised again in 1988. Also long before Thatcherism, the Conservative government privatised the travel agency Thomas Cook in 1972, and in 1977 the Labour government sold a chunk of the government’s majority stake in British Petroleum.

However, in line with the supposed state-market antithesis, leftists perceive nationalisation as a radical attack on capitalism’s ‘neoliberal’ market values. Right-wing commentators, in turn, think it amounts to revolutionary Marxists going for the keys to No10. In fact, Labour’s nationalisation proposals are also quite consistent with normal capitalist practices in Europe, the US and Japan. They would bring Britain back more in line with many other mature capitalist countries who operate nationalised utilities.

Opinion polls show that nationalisation is popular with the electorate today. This is primarily for more pragmatic reasons than its historical association with state socialism. It is because the private provision of utilities has become as unpopular as the previous nationalised provision was 40 years ago. People are fed up with private franchise trains that are overcrowded, late and dirty; with water companies that can’t seem to prevent ubiquitous leakages and then threaten hosepipe bans whenever the sun shines for more than a fortnight; and with energy companies that have pricing systems that punish loyal customers and require us to waste time switching providers.

Just as the proverbial grass seems greener on the other side, state ownership seems preferable than the existing service. If someone suggested nationalising cramped low-cost airlines that charge extra for taking a modest piece of luggage with you, or the shoddy house-builders that can’t build decent homes fast enough, or insurance companies that penalise existing customers with high renewal premiums, then a lot of people would probably say that wouldn’t be such a bad idea either.

But that appeal to our instinctive interests as consumers ignores that we are also taxpayers, who might end up subsidising bureaucratic state-owned operations. And it ignores, too, that many of us work for these same poorly performing businesses, and know that a lot of the problems derive ultimately from long-term underinvestment, which is not going to be reversed simply by swapping private for state ownership.

Labour’s broadband plans would be akin to a 19th-century government completing a nationwide network of canals to every town, just as rail begins to take off

Given that the state and the market always have been inextricably intertwined – and to a greater degree since the 1950s than ever before – much more important than levels of state spending or taxation, or the choice between state control through regulation or through direct ownership, is the question of democratic accountability over what the state does.

Nationalisation itself offers no answer for these matters. Contrary to Labour’s manifesto assertion that ‘public ownership will secure democratic control over nationally strategic infrastructure’, there is no automatic connection between state ownership and democratic control.

In considering nationalisation specifically as a form of state economic intervention, what issues should occupy us about government accountability? Here are three of them. For a start, I agree with Brendan O’Neill that we should be concerned about how direct state control can infringe our freedoms. Nationalisation of the communications network, in particular, would make state intrusion and potential censorship of our communications easier.

There are also two big economic matters. The first is how different forms of state intervention might assist innovation and productivity growth – rather than hold back growth, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Often this is not a simple yes or no question. Trying to preserve the status quo to keep hold of jobs might seem appealing but it comes at the cost of continued productive decay, leading to deteriorating job quality and security. Disruption to business activities will be a necessary step towards economic renewal. So, as voters, we need to judge the long-term potential of any policy to create durable jobs and prosperity over short-term inconvenience.

The central question for any party’s proposed economic programme should be whether it breaks from the pattern of the past four decades of policies that have predominantly propped up an increasingly decrepit economy. The Corbynite plan to spend more money and extend state ownership and regulation does not give an answer. The manifesto pledge to ‘let struggling companies go into protective administration… rather than collapsing into insolvency’ suggests a continued preference to sustain zombie businesses rather than allow them to go under, which would clear the way for innovative businesses to start up or expand.

A common feature of preservationist rather than transformative industrial strategies is that of governments ‘picking winners’ – that is, acting to identify and support particular companies, sectors or business strategies. This approach always tends to perpetuate the present and reinforces constraints on change and progress. Labour’s manifesto reflects such a restricting approach that can be detrimental to innovation. Take the ‘radical’ proposals to take direct control of the communications network and roll out ‘full-fibre to all’. It confines a large chunk of society’s resources into soon-to-be outdated technologies, creating a barrier to alternative, potentially much better, communications investments by the state or by others. Labour’s broadband plans would be akin to a 19th-century government completing a nationwide network of canals to every town, just as rail begins to take off. Even today, and especially for premises in remote areas, satellite, hybrid or other wireless or fibreless provision may be much more suitable than Labour’s pledge of fibre for all.

The other significant factor to consider about nationalisation is incentives. Financial incentives, especially today, often operate in a blunt and distorted fashion, but they still provide the framework where line managers and workers are encouraged to do their jobs well. One problem with state intervention is that it blurs or waters down those businesses’ financial incentives for producing a decent service at a reasonable price to end-users. If a commercial business is state subsidised, then the drive to produce efficiently is at least weakened, if not neglected completely. This compounds the potentially adverse effect of state interference on productivity growth.

When an operation is fully nationalised, the damage to material incentives is even greater. An effective, potentially even more powerful, alternative to financial incentives is a culture of public spirit or civic duty held by those working in these state operations. Some of the nostalgia around the NHS and state education arises from how many people working in these areas – nurses, doctors and teachers – used to see themselves as performing a duty for the rest of society. It was not just a job, but a vocation. To some extent, this belief in providing a public service inspired people working in other state-run organisations, from social work to the postal services, and even extended to nationalised water provision and railways.

The decline experienced in most Western countries over the past half-century in the ideals and values associated with a culture of public service has contributed to the deterioration in standards. It is certainly true that the lack of public investment has demoralised workers in these sectors. But it is too narrow to blame everything on a shortage of funds. Cultural shifts have also had a negative effect on services.

Virtues like loyalty, solidarity and altruistic behaviour have been disparaged by the bureaucratisation of public life. Social isolation has taken over from the idea of having something in common with others. As people increasingly see themselves surviving in a more atomised, less cohesive society, this rubs off in a dispirited, disengaged approach to their work, including by those supplying state-run services.

Until societies regain a deeper sense of meaning and purpose, this loss of the public-service ethic needs to be considered by people in assessing any proposals for nationalisation. It is not just a matter of whether an enterprise is state- or privately owned: it is about the motivation to perform a decent job. Voters should be thinking less about the percentage of GDP in state budgets and more about the best way of reviving the virtues of courage and risk-taking that underpin public-spiritedness. How people regain a sense of collectivity and loyalty to others is a key question.

In conclusion, there are much more serious issues we as the electorate should be examining than levels of public spending or the technical ways that the state exercises control of the economy. In particular, in the spirit of democratically honouring the 2016 referendum result, we need to consider how to revive a spirit of public purpose and duty. This pertains both to our civic lives and to our working lives, not least for those of us who happen to work today, or potentially tomorrow, in state-owned enterprises. Recreating a public belief in control and in our potential for positive improvement is the genuinely radical shift we need for cultural, social and economic transformation.

Phil Mullan’s latest book, Creative Destruction: How to Start an Economic Renaissance, is published by Policy Press.

Pictures by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.