Long-read

The myth of Corbyn’s radicalism

Corbyn’s Labour would preserve the capitalist status quo, not challenge it.

As the clock ticked closer to 31 October, a favourite summertime teaser was what should people in Britain most worry about: a no-deal Brexit or a government led by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell? With so much fearmongering in the air about Brexit, it was still striking that many business leaders claimed to dread a Corbyn government even more than going over the proverbial Brexit cliff.

Financial investors told us that they, too, are spooked by Labour’s pledges to nationalise the railways and the regulated water and energy utilities. Consultants have been busy working overtime to protect their clients’ assets from the possibility of ‘expropriation’. And the rich have been checking the robustness of their tax-avoidance schemes, while fleeing to overseas tax-shelter retreats. Quite a few political conservatives also anticipate that the election of a Corbyn-led government risks bringing the curtain down on British capitalism. The thought that ‘real Marxists’ could be occupying Nos 10 and 11 Downing Street certainly makes some of them shudder.

Given the fears generated by the prospect of a Corbyn-led government, just how radical is it likely to be? Should we really expect Britain’s first anti-capitalist government? Certainly not on the basis of what Corbyn and McDonnell and their cheerleaders have been writing and saying about their future Labour government.

One indication that establishment critics are getting a little carried away comes from the politics of those with an ultra-left heritage who are among the most enthusiastic about the prospect of Corbyn as prime minister. Among his most outspoken backers are those on the modern ‘accelerationist’ left. They are called this because they want capitalism to be accelerated, rather than overthrown 1917-style, in order to bring about radical social change. This band includes ‘postcapitalist’ utopians, like the writer and broadcaster Paul Mason, as well as ‘fully automated luxury communists’ such as Aaron Bastani and others around his left media organisation, Novara.

These people have evolved traditional leftist economic determinism into today’s more fashionable technological determinism. Modern social-media communications and ‘platform’ operations such as Uber and Airbnb are thought to be breaking down capitalist social relations and taking us ‘beyond’ capitalism. Discovering this liberating impact of technology is convenient, since the left-wingers promoting it have lost confidence in being able to convince working people of the need for action to overcome the limits of capitalism.

In the interim, as the post-capitalist accelerationists wait for new technology to do its thing, they have identified themselves with Team Corbyn’s ‘radicalism’.

Shadow chancellor McDonnell, usually described as the brains behind this new Old Labour, has expressed his sympathy with the accelerationist outlook. When asked if he still wanted to see the end of capitalism, he answered, ‘It’s evolving anyway. It’s a system I think will evolve out of existence.’ It seems evolution has displaced revolution in the modern anti-capitalist playbook.

The state of today’s Labour Party captures the desperate plight of genuinely radical politics

The mania about Corbynism from both right and left is therefore itself a strange thing to consider. Especially when even a quick read of Labour’s 2017 manifesto — For the Many, Not the Few — reveals that a lot of it could have been cut and pasted from the Conservative or Liberal Democrat manifestos. Balancing the budget; fiscal ‘credibility’ rules; reducing public debt; making Britain a fairer place for all; an industrial strategy to revitalise the economy, and so on. Not only are they far from ‘radical’ suggestions — these are now orthodox mainstream political positions.

Moreover, Corbyn made this very point when addressing the Labour Party conference three months after the June 2017 General Election. The Labour Party, he told delegates, now represented ‘the real centre of gravity of British politics … We are now the political mainstream.’ Maybe his speechwriters were trying to be a little ironic in the face of his reputation as a hard-left extremist, but as the adage goes, many a true word is spoken in jest. Most of today’s Labour programme is conventional thinking, embellished with a little more moralistic hyperbole.

This signals a peculiar mismatch between the perception and the reality of Corbynomics. In more normal times, the manifesto wouldn’t have raised much of a stir, either positively or negatively. However, today’s abnormal political climate has elevated Corbyn and his associates. Recall the ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn’ adulation from the crowds at 2017’s Glastonbury festival. That level of youthful passion may seem from another age, but it was only two years ago. Even after the exhaustion of that infatuation phase, and the ensuing ructions over anti-Semitism, the continuing impact of Corbynism remains significant. It tells us much more about the dire condition of politics than it does about the content of Corbyn’s programme.

For the left, Corbyn’s elevation to the top of a party once associated with the working class is grasped as a sign that Labourism is not completely irrelevant. It helps sweep away Labourites’ inability since the 1980s even to say much of substance in support of working people. Three decades spent promoting identity politics, culture wars and name-calling against a manufactured ‘neoliberalism’ seem worth it now that ‘socialism’ is apparently ascendant again.

Some imagine that Corbynism’s far-reaching appeal from the far left to parts of the centre- and soft left indicates an essential vitality. In fact, any magnetic attraction retained by Corbyn reveals the plight of genuinely radical politics, as well as the emptiness of Labour. Left-wing idolisation of Team Corbyn smacks of desperation when so many individuals and groups can put their often dogmatic, ideational histories aside in favour of association with this accidental anomaly. Even now that a lot of the youth have lost their initial belief in Magic Grandpa, while a straw of hope remains the left can be expected to grasp it.

Meanwhile, the fearful attitude of the old right and of parts of business to Corbyn is the reverse phenomenon. They also sense emptiness when it comes to setting out what they are trying to achieve these days. The vacuity of the Tory leadership contest was bad enough. But with no one able to make a positive intellectual case for capitalism, the political and business elites are genuinely anxious about the future.

For a moment, anyway, Corbynism offers them something to define themselves against. A bit like how the Cold War demonisation of Communism provided a negative legitimation for Western capitalism, so Corbynism seems to provide the old elites with a temporary source of coherence. ‘We may have no good ideas of our own for how to hold society together, but at least we can take a stand against the dangerous Marxism of those crazies, Corbyn and McDonnell.’ The irony is that if Corbyn does come to power, this strawman foe would soon be exposed as pretty harmless.

Defining Corbynism

How can we describe the new Labour Party message? On its own, the content of Team Corbyn’s ideas barely justifies being an ‘ism’ or ‘omics’. It’s hard to distill an essence of Corbynomics, or to define it as a coherent set of economic policies. Perhaps this is why so many attribute its intellectual underpinnings to Tony Benn and his Alternative Economic Strategy from the 1970s and 1980s. However, this comparison does a disservice to Tony Benn’s ideas, and flatters Corbynomics.

The original Alternative Economic Strategy had intellectual coherence. It was the outcome of decades of radical reformist thought known as ‘State Socialism’. This was the idea, which originated in the Second International federation of socialist parties at the dawn of the 20th century, that through taking political control of the institutions of state, possibly through elections, it would be possible to bring about a socialist society. It obviated all that messy revolutionary business Lenin and Trotsky got involved in, such as storming barricades and expropriating the expropriators.

Opposing Corbynism seems to provide the old elites with a temporary source of coherence

In comparison to the Alternative Economic Strategy, Labour’s new programme is a mishmash of proposals. It lacks coherence, pulling together disparate suggestions from a range of sympathetic groupings. As a set of policies Corbynism is a hotchpotch, amalgamated from the desires of those attracted to the faint light of the Corbyn flicker. A bit of ‘municipal socialism’ here, a bit of ‘co-operativism’ there. Add in a bit of environmental sustainability, a bit of industrial strategy, and the tempting idea of reversing some of the failed privatisations from the 1980s: water, power and rail.

We should recall that Corbyn’s election as party leader did not follow a hard-fought campaign over alternative ideas and policies. Matthew Bolton and Harry Pitts, two self-described Marxists who have written a substantial critical examination of Corbynism, explained that Corbyn was more beneficiary than instigator of the Labour Party’s apparent shift to the left (1). In choosing Ed Miliband’s successor after the 2015 General Election defeat, Corbyn was the token hard-left candidate by Buggins’ turn. Diane Abbott had that privilege in the previous contest in 2010, scoring seven per cent in the first-round vote among Labour MPs.

As has been much commented on, in 2015 Corbyn was even nominated by some moderates to make sure he could get on to the candidate list and offer the appearance of a credible leadership contest. He won by accident, not because of a radical surge. The uninspiring ‘serious’ candidates he was up against undoubtedly helped his victory, itself a symptom of Labour’s long-term decline. Upon his unexpected election, his supporters, centred on a hardcore of about 40 MPs, quickly assembled a team to help cook up something for him to say in his capacity as Leader of Her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition.

In its own terms Corbynism is mostly defined negatively. Its big claim is that it stands against the ‘neoliberal’ economic policies that have ‘dominated government thinking’ since the late 1970s. Supposedly, for nearly 40 years, Britain and the world in general have been controlled by the idea that markets are the ‘best possible means to organise an economy’, while the state has receded into the background. The regulation of business has been ‘reduced to irrelevance’ (2).

This is tilting at windmills. The British economy, in line with all other mature economies, has been subject to steadily more regulation and state control ever since the 1970s. For example, Andrew Haldane, the Bank of England chief economist, pointed to a near 40-fold increase in financial regulation over 30 years. While in 1980 there was one UK regulator for every 11,000 people employed in finance, by 2011 this had expanded to one for every 300 (3). Empirically, this is a curious-looking de-regulation. Even when parts of the economy were privatised in the 1970s and 80s, this was accompanied by an upsurge in official regulation in place of direct public ownership. State control did not weaken; it merely changed form.

Targeting an imaginary ‘small state’ enemy is rather easier than explaining positively what you stand for. Sure, Labour espouses a ‘fairer’ society but this doesn’t define an economic programme, either. Attacking a few at the top of society is not sufficient to benefit the many. Nor is it distinctive within today’s caring brand of capitalism. Advocating a more socially aware version of capitalist operations does not tell us much, especially when it is the mantra of just about every Western business grouping.

As that well-known proto-socialist publication the Financial Times noted, ‘Politicians across the political spectrum have been searching for a response to the sense that the UK’s economic and social structures do not give all of its citizens a fair chance’. Corbyn and McDonnell are part of that consensus, not extremists in opposition.

If the policies themselves are not that original, their framing does appear more resolutely focused against inequality. Surely a Corbyn government could be distinctive in standing up for the working person…

‘If you’re from an ordinary working-class family, life is much harder than many people in Westminster realise. You have a job but you don’t always have job security. You have your own home, but you worry about paying a mortgage. You can just about manage but you worry about the cost of living and getting your kids into a good school.

If you’re one of those families, if you’re just managing, I want to address you directly. I know you’re working around the clock, I know you’re doing your best, and I know that sometimes life can be a struggle. The government I lead will be driven not by the interests of the privileged few, but by yours.

We will do everything we can to give you more control over your lives. When we take the big calls, we’ll think not of the powerful, but you. When we pass new laws, we’ll listen not to the mighty but to you. When it comes to taxes, we’ll prioritise not the wealthy, but you.’

These could be Corbyn’s words. But they were in fact the words spoken by Theresa May on the day she became prime minister. Her pledge was to make ‘Britain a country that works not for a privileged few, but for every one of us’. Leave aside her government’s lack of follow-through, and consider the contrast between these words and Team Corbyn’s favourite mantra: for the many, not the few. It’s hard to discern much difference.

The 2017 Labour manifesto promoted another telling phrase about taking on the ‘rigged system’, rigged by the few for the few. In its manifesto, Labour pledged to ‘rewrite the rules of a rigged system’ so that the economy really works ‘for the many’. Apart from this sounding similar to May’s pledge to stand up against the entrenched ‘advantages of the fortunate few’, Labour’s emphasis on the rigged system does point to a significant aspect of their thinking about what is wrong with Britain.

The problems of British capitalism are not perceived as systemic. Instead, a privileged few at the top have ‘fixed’ things in their own interest at the expense of the rest of us. This epitomises their personalised and moralistic critique of capitalism. The workers create the wealth and the bosses and bankers steal it. The argument follows that rewriting the rules – clamping down on the privileged with higher taxes, tougher controls on what they get paid, and regulations with all the loopholes sealed shut – can make the country fair for the many.

Supposedly, the business elites have conspired to steal public funds to serve their own greed. But this thesis turns upside down the growing dependence of anaemic, profit-constrained, underinvesting businesses on the resources of the state. This becomes proof of the corporate colonisation of society. From the perspective of the takeover of the political system by the bogeyman of ‘neoliberalism’, the expansion of direct and indirect state subsidies is presented not as a business-sustaining life preservation, but as an illustration of corrupt ‘crony capitalism’.

There is nothing original in Labour’s personalised view of the maladies of capitalism. Over the decades writers like Martin Wiener, in English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, 1850-1980 (1981), and Geoffrey Ingham, in Capitalism Divided? The City and Industry in British Social Development (1985), have popularised this view. New Left writer Robin Blackburn also sympathetically summed up this perspective, writing that the ‘maladies of the British economy extend back far beyond the present era. Capitalist landowners and City bankers had turned their backs on the UK’s productive economy even before it lost its first-industrialiser advantage in the 1870s.’ (4)

The left has a long tradition of targeting ‘fat cat’ capitalists and international financiers. Since the 1980s, this personalised critique of capitalism has evolved to highlight also the influential role of shady neoliberal individuals and groups who have manipulated the system to benefit the few at the expense of the many. From this view, economic stagnation turns from being a systemic feature of late capitalism into a conspiracy peddled by Hayekians and supporters of the Chicago School of free-market thinkers.

Labour sees the problems of British capitalism not as systemic, but as the fault of a privileged few

Especially since the financial crisis, attitudes towards productive decay have assumed an even more moralistic tone, focusing on greedy bankers and tax-avoiding business leaders. This draws on a caricature of people immorally manipulating affairs for their own narrow interest at the expense of the rest of us. The flourishing of leftist identitarianism that divides society between the privileged and so-called victim groups further fuels it. In economic matters, the rich and their political supporters occupy the privileged category that rig the system, while the rest of us, the many, consequently suffer varying levels of financial hardship.

Attributing the economic crisis to schemers and conspiracists frames it as not just unfair and immoral, but as ultimately unnecessary. If only the rich and their neoliberal ideologues had been resisted, or at least better controlled and regulated, then the financial crisis and the hardships that followed could have been avoided. The capitalist system’s perennial tendency to break down is reduced to the unscrupulous actions of particular people.

Ironically, this leftist personalised view of what’s gone wrong with the economy is mirrored by Conservative opinion, though with different targets. In the 1970s and early 1980s, pushy trade unionists were said to be to blame for inflation and industrial degeneration. By the 2000s, the right’s spotlight had turned on spendthrift social-democratic politicians who were bankrupting society. Even 10 years on from the financial crash, we still hear senior Tory politicians blaming economic sluggishness on New Labour’s extravagant spending on public services. All of which ignores the inconvenient fact that the 2008 crash originated in the US debt bubble.

The problem with Labour’s personalised explanations for the crisis, however, is not just their superficiality. It is that they also sanction capitalist apologists’ desire to blame certain individuals and groups for their system’s malaise. This helps explain Corbynism’s inability to deal decisively with anti-Semitism in the Labour Party.

Whoever is targeted, the consequence is the same. Public discussion about the deeper structural barriers to growth is sidestepped. Instead we have platitudes about working for the many, not the few. They meant nothing when spoken by May. On their own, such words will not mean much more coming from Corbyn, or from any other Labour Party prime minister.

Let’s turn to the specifics of Labour’s proposals. Corbynomics, and Corbynism in general, are neither as extreme nor as nonconformist as is thought both by critics and supporters. Nor is Corbynism radical, in the literal sense of getting to the roots of Britain’s economic malaise. Much of what is being promised is in tune with the conventional thinking that has already been perpetuating the Long Depression. In consequence, Labour’s proposed economic policies would extend the practice of sustaining Britain’s zombie economy, rather than bringing this to an end.

Extremist?

Labour’s headline pledge is nationalisation. Does this mean taking over the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy, a traditional Labour Party demand? Can we expect public ownership of Big Pharma and the ‘too big to fail’ financial institutions? Will we see the seizing of private airports and foreign-owned car plants? What about nationalising British Telecoms, British Aerospace or British Petroleum? There are no plans for any of this.

Labour has stressed that its objective is simply to reverse the earlier privatisation of infrastructure utilities like water and power, alongside rail companies and Royal Mail. As McDonnell put it in The Sunday Times, ‘this is the limit of our ambition when it comes to nationalisation’.

Investors in the targeted private companies are understandably anxious about compensation terms. But as a political programme, this is strikingly modest compared to what the Labour Party used to say about extending state control. From 1918 until as recently as 1995, Clause Four of the Labour Party constitution committed it to ‘secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service’.

Compared to Labour’s radical reformist tradition, today’s Labour is remarkably tame. The high prices, poor service and inadequate investment undertaken by most of the private-utility owners make this one of Labour’s most popular proposals. But it is hardly an incursion on ‘free-market neoliberalism’. Corbynomics seeks merely to reverse the privatisation of sectors that are mostly natural monopolies, areas always unsuited to market competition. There was never much prospect of competitive capitalists building alternative rail, water or power networks.

By conforming to what has gone before, Corbynomics would perpetuate measures that have been sustaining the zombie economy

All these privatised concerns remained heavily regulated by the state, through various bodies: Ofwat, Ofgem, Ofcom and the ORR (Office of Rail and Road). These impose statutory obligations and restrictions on what the private companies can do. Either directly or indirectly, the government also influences consumer pricing, including controlling wholesale charges for energy, and price setting for water and for about 40 per cent of rail fares. It is ironic that the supposedly extremist Corbyn-McDonnell Labour Party is promising to expropriate some of the countries’ most regulated companies, not parts of the economy where market forces might be, if far from rampant, a little less fettered by the state.

However, the real drawback with Labour’s plans is not their limited reach. It’s that in extending state ownership, no matter how modestly, it would perpetuate a sickly mature economy’s dependence on the state.

The original Clause Four drew on the old reformist idea that state control equals ‘socialism’, a conception that had nothing to do with revolutionary Marxism. In fact, by the early part of the 20th century, state organisations in the most developed countries had for a long time run parts of the capitalist economy, from railways to postal services and utilities – precisely the areas Corbyn’s Labour Party is targeting today. Far from taking us into the sunny uplands of socialism, Labour’s nationalisation plans return us to the capitalism of the late 19th century.

National control of infrastructure and utilities is not an extremist measure. It’s the norm in most Western countries. Currently, state control of the railways rules in Germany, Spain, France, Italy and Ireland, as well as parts of rail services in Japan, and intercity passenger services in the US. Would anyone call these extreme socialist countries? We shouldn’t forget that Britain’s rail infrastructure is already owned, maintained and operated by state-owned Network Rail, as is the whole rail service in Northern Ireland. Does this make the ruling Conservative government partly socialist? No, it means that state ownership is an established feature of advanced capitalism.

Most countries in the developed world also run their water services on a state-controlled municipal basis. In the ‘socialist’ US, 88 per cent of people are served by public community water systems, and 12 per cent by private ones. Further change in this direction cannot be described as ‘extremist’. Already in the past 15 years, 235 cities in 37 mostly high-income countries have taken their water into public ownership. The Netherlands has even made water privatisation illegal. Let’s recall that even in the UK, public control dominates water services in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland; only in England is the service still in private hands.

We are also seeing the extension of state ownership of the private sector as a by-product of today’s official attachment to ultra-easy monetary policies. As part of its quantitative easing (QE) programme, the Bank of Japan has been buying company shares through exchanged-traded funds totalling now to the equivalent of about five per cent of its annual economic output. The European Central Bank has been considering doing the same thing as it expands its own QE. In content there is not much difference between state treasuries buying up private company shares, as Labour suggests, and state banks doing the same thing.

How does the Corbyn team reassure their core supporters of their socialist credentials when state control has become so ordinary and non-extremist? There is nothing new in this, either. The perceived extremism of the policy of nationalisation has for a very long time drawn upon its use in Russia after the 1917 October Revolution. Twentieth-century social democracy falsely associated a practical way of organising a socialist economy when the Russian capitalist class had been politically disempowered as being the equivalent of the achievement of socialism elsewhere. As promoted by reformist organisations like the British Labour Party, state control of industry became a substitute for, not the realisation of, revolutionary change.

State ownership, sometimes described erroneously as ‘workers’ control’ of production, doesn’t negate the organisation of production on capitalist lines. We have had enough experience of nationalised industries and cooperatives in multiple countries over the past 150 years to know that a change of ownership does not overturn or even transform capitalist society. Regardless of who owns businesses – shareholders, the state, or the employees – production is still geared towards the market rather than social needs. The crisis-prone workings of capitalist society are not resolved. There will always be market failures within capitalism, but state ownership of industries does not banish them.

It is true that state ownership of enterprise can have some redistributionist effect. Dividends that used to be paid into share-owning pensions and insurance funds and to other shareholders, domestic and foreign, could be kept within the business. But retaining more of the profits doesn’t necessarily translate into more capital investment in new technology and innovation. Without that, public ownership is just another mechanism for subsidising low-productivity operations.

The specific recurring problem with capitalistic nationalisation is that nowhere has it generated incentives for management and workers that can improve on those from the market system, inadequate as those are. From the 1970s on in Britain, it became increasingly evident that workers in nationalised industries – as well as most providing public services – lacked the incentive in spirit to provide first-rate services. Without substantive involvement from frontline workers driven by a real public-service ethos, operations became increasingly bureaucratic and detached. Service levels to the citizenry deteriorated. Decent wages alone can’t fill this incentive gap. Nor is it likely that having a few more workers on the boards running these industries will resolve these problems.

Workers’ ownership

Labour’s suggestions for other ‘alternative’ forms of business ownership are no more extreme than its plans to re-nationalise privatised monopolies. The broad objective is for workers to own some or all of the enterprises for which they work. This includes encouraging the spread of employee-owned firms on the cooperative model, and legislating for larger ones to give workers gradually up to 10 per cent of company shares, to be held in an ‘inclusive ownership fund’.

These shares would be held and managed collectively by the employees, and give all the workers a right to dividends. But it seems the ordinary employee shouldn’t have too much of a good thing. Labour policy would cap dividend payments to workers at £500 a year, while any returns for the workers’ fund above that level would be given directly to the government. In practice this scheme would act as an extra tax on businesses, with any dividend cap appearing as an employee tax.

Unsurprisingly, the proposal is unpopular with business leaders. However, claims that this represents one of the most extreme shake-ups of British business ever are rather exaggerated. Far from challenging capitalist property relations, this scheme might simply give workers an annual bonus – more money is always good – as well as an incentive to drive up corporate profits. The impact might not be that different from older non-revolutionary practices such as performance-related pay.

There is nothing anti-capitalist about these suggestions for alternative ways of owning and running businesses. Changes in ownership can alter the distribution of value, but they do nothing to transcend the capital-imposed limits on value creation. Labour effectively admits this when it explains cooperatives’ ‘chief’ benefit: greater stability of employment. Workers’ cooperatives could adjust labour costs in response to adverse economic conditions by ‘decreasing wages and hours, rather than decreasing employment’ (5).

Labour seems to think that increasing cooperative forms of ownership would ‘tackle the increased insecurity, inequality and lack of control over working life arising from the dominance of privately owned and controlled firms’ (6). This turns capitalism’s constraints on development into the actions of particular bosses or financiers who own and control private firms. Changing forms of ownership do not affect how the law of value systematically frames and holds back the advance of productivity.

Companies in many Western countries have higher levels of employee ownership and representation than in Britain. Germany has a cooperative sector much bigger than Britain’s, with rules requiring large firms to have workers on their supervisory boards. Other European countries, including France, Norway and Sweden, also have regulations requiring board-level employee representation. This type of approach has also been taking off in the US, where it is called the ‘B Corp’, originally derived from the term ‘Benefit Corporation’. This has now become a certified ‘responsible corporate’ structure. To qualify, a firm has to prove it will look after the interests of its employees, customers, as well as society at large and the environment. Yet none of this protects these workers from the vagaries of the capitalist market; and none ensures faster productivity growth. Employees across these countries still experience ‘insecurity, inequality and lack of control’ over their working lives.

Labour’s 2017 manifesto promised to double ‘the size of the cooperative sector in the UK, putting it on a par with those in leading economies like Germany or the US’. The goal of emulating those well-known bastions of socialism, America and Germany, reveals a lot about the non-transformative consequences of Labour’s plans to expand workers’ ownership.

From the John Lewis model in Britain to Germany’s system of worker participation and America’s B Corp, Labour’s current proposals look anything but extreme. Tellingly, the 2017 manifesto even noted that the ‘majority of businesses play by the rules: they pay their taxes and their workers reasonably and on time, and they operate with respect for the environment and local communities’.

It identified the problem facing workers as well as ‘good’ businesses as the underhand antics of the ‘unscrupulous few’. Given this official endorsement of many existing businesses as doing the right thing, Labour’s ownership proposals offer another instance of the incoherence of its full programme. If only a nasty few are at fault, why propose change across the whole business environment?

Nonconformist?

There is nothing unconventional in Labour’s diagnosis of the structural barriers to growth, nor in its proposals to overcome them. The core idea is that inadequate demand is holding the economy back, a traditional Keynesian notion. The suggested solution starts with boosting demand through a combination of fiscal and monetary stimulus. This is also a solidly conventional approach, which has been adopted by governments of all political hues, especially since the 2016 ‘populist’ votes.

In fact, ever since the 1940s, expansionary fiscal policies have been standard fare for British and Western governments in times of economic sluggishness. It is true that for the three decades between the 1970s and the aftermath of the financial crisis, most Western governments shied away from applying the ‘Keynesian’ label for these practices, despite continued taxing and borrowing to spend. Explicit Keynesian ‘pump-priming’ had been discredited, after being blamed by the left as well as by the right for 1970s ‘stagflation’ — that is, for the new combination of weak economic growth with high inflation.

Thereafter, for several decades anyone promoting a positive policy of tax, borrow and spend would be described either as antediluvian or as labourist, and could usually see themselves as being honourably ‘nonconformist’. The reality was different because high fiscal spending, often financed by borrowing, continued even when the ‘anti-state’ rhetoric was most fervent in the US and the UK in the 1980s.

The reason for this is that sluggish productivity never recovered and economic life became increasingly dependent on extensive state spending. This was not just about stubbornly elevated spending on personal welfarism to offset the effects of joblessness and of in-work financial hardship. These economic conditions also brought the expansion of corporate welfarism. Governments provided a range of corporate tax breaks, subsidies and spending on supplies of goods and services that sustained private business sales and profits (7). High state spending, not government budget surpluses, has been the conforming norm in most countries.

It is true that for the first few years after the 2008 financial crash most governments did react to the spiraling public-debt levels with calls for fiscal restraint. But even under the banner of ‘austerity’, borrowing to spend continued almost everywhere. Labourist demands for extra state spending were therefore never as nonconformist as they seemed.

In the past couple of years, politicians and central bankers have become much less resistant to the concept of increased public spending, despite its obvious association with Keynesianism. This is born out of desperation, a growing sense that something more needs to be done to keep Western economies afloat.

The Labour Party’s economic programme is simply a more caring version of modern economic orthodoxy

International institutions like the IMF and the OECD, having preached fiscal discipline, are now encouraging governments to spend more. ‘A crying need’ for governments to spend more was the recent exhortation from Laurence Boone, the OECD’s chief economist. Central bankers, who are more aware than most of the exhaustion of their own monetary policies as well as the financial asset bubbles they are causing, have been especially outspoken in wanting governments to do more.

This year’s annual report of the ‘central bankers’ bank’ — the Bank for International Settlements — called for governments to remove some of the load from central banks in supporting the economy. It wants them to unveil stronger fiscal policies as well as structural reforms. As his term as president of the European Central Bank draws to a close, Mario Draghi has been making a similar claim. ‘Over the past 10 years’, he lamented, ‘the burden of macroeconomic adjustment has fallen disproportionately on monetary policy’. Referring to instances where government spending restraint has even countered monetary stimulus, he argued for accelerated work on a big enough ‘common fiscal stabilisation instrument’ (8). In late August the central bankers’ annual gathering at Jackson Hole, Wyoming reiterated this appeal.

The notional ‘independence’ of central banks seems to be contested by central bankers as much as by some politicians. Central bankers have turned into cheerleaders pressing politicians for fiscal expansionism. If they had the inclination to study Labour’s stimulus proposals, these bankers would be unconcerned. In fact, with Labour’s manifesto pledge to ‘balance the books’ and its commitment to ensuring ‘the national debt is lower at the end of the next parliament than it is today’, its proposals are actually less extreme than those made by some central bankers recently.

Although fiscal activism is becoming fashionable again, that will not make it any more successful in reviving a stagnant economy. Spending more public money does not itself transform production and raise productivity. Any policies based on demand stimulation are saddled with the usual flaws of state spending over the past four decades. Without a parallel renewal of productive operations, at best more demand just helps sustain the existing productive capacities. This can support economic activity in the short term, as illustrated by Donald Trump’s US over the past 18 months. However, in the medium term this turns into sustaining out-of-date production processes, and relieves pressures for innovative capital investment. Productivity growth remains semi-comatose and for many households incomes will continue to stagnate.

Reliance on easy monetary policies will not help here. It actually makes things worse by sustaining debt-funded zombie businesses. Labour’s support for monetary expansion equally conforms to conventional practice. Labour has said very little about the growing criticisms that these ultra-loose money policies are both ineffective as well as counterproductive for economic growth.

Just as with fiscal activism, Labour’s approach to monetary policy is also on the modest side. Possibly to avoid the accusation of infringing on the Bank of England’s ‘independence’ as established by its Labour government predecessor in 1997, the manifesto says nothing explicitly about it. The manifesto also omitted the phrase Peoples’ Quantitative Easing (QE) that Team Corbyn had initially promoted.

Nevertheless, Labour has continued to advance a monetary policy with similar content to Peoples’ QE. Although it does not have an agreed definition, it usually refers to central banks going beyond the conventional practice of purchasing financial assets, usually government or corporate bonds. The stated aim of this now ‘traditional’ QE was to reduce longer-term interest rates with the goal of helping to boost borrowing and spending by businesses, as well as by richer people whose financial wealth would also grow.

The ‘people’s’ twist on QE is for state banks not just to buy government bonds in the hope the extra liquidity filters through to the economy, but also to issue bonds for a particular purpose. Some want the new money to be given directly to people and small businesses to spend. Others, like Corbyn and McDonnell, have said the new government funds should be used to spend on public infrastructure that would also help people, if less directly. This idea features in the manifesto as a National Transformation Fund, established with new government borrowing of £250 billion. This money would be earmarked to invest mostly in transport, communications and energy systems.

It is ironic that Labour has resisted talking about ‘People’s QE’ at precisely the time that many others in the mainstream are now discussing how to adjust or develop QE to make it more effective. Similarly, just about every other political party is now aligned on the need to spend more on national infrastructure. Labour’s quiet monetary policy plans are again conforming to modern conventional thinking.

Conformism applies also to Labour’s industrial-strategy proposals. Labour, like the IMF and the OECD, identifies the fundamental structural flaw of the British economy as a lack of long-term investment and declining rates of productivity. Likewise, it sees the solution as more spending not just on infrastructure, but also on research and development (R&D), on education, and on skills improvements. These are the core measures in Labour’s proposed industrial strategy. In substance, this is little different to the Conservative government’s existing industrial strategy.

Even many right-wing economic liberals favour state intervention to support capitalism

Labour’s linked emphasis on regional development to rebalance the economy is also commonplace. A brand consultant arriving from Mars who read Labour’s manifesto might suggest a ‘Northern Powerhouse’ or a ‘Midlands Engine’ would be inspiring tags to use, but the Tories have already bagged them.

It is true that Labour’s industrial policy targets are sometimes a little more ambitious in quantity or in speed of execution. But what matters more to their potential impact is the direction of travel, and this doesn’t break from the recent mould. For example, Labour proposes a National Investment Bank to bring in private capital finance to deliver (another) ‘£250 billion of lending power’. Nothing ‘extreme’ or ‘nonconformist’ in this. There are already many similar public-investment banks around the world. Hence Labour’s manifesto acknowledges that it is merely following ‘the successful example of Germany and the Nordic countries’.

More pertinently, this initiative is targeting a mythical funding gap. There is no absolute shortage of funds to invest. Banks and other financial institutions have plenty of liquidity to lend at historically low rates. But even many stronger businesses have not been borrowing to invest in innovation and new technologies. The real issue for any government is how to create the conditions for such investment to take place, not to make borrowing easier and easier. The latter is the proverbial pushing on a piece of string.

Labour’s own proposals for revamping industrial strategy offer little indication as to how effective they will be. Building ‘a million homes’ and meeting the ‘OECD target of three per cent of GDP spent on research and development by 2030’ can be taken as helpful aspirations. But outcomes are far from certain, especially when it is not spelt out how targets can be achieved.

Of course, an election manifesto can’t be expected to go into that much detail. But the failure to explain why similar sounding plans have been so ineffective in the past is revealing. This points to the main flaw with Corbynomics. By conforming to what has gone before, and by failing to critique the substance of past policies, it would perpetuate measures that have been sustaining the zombie economy.

Radical?

The core problem with Corbynomics is not that it is insufficiently radical. It is that, if implemented, it would compound the problems of low investment and weak productivity growth. This is because the Labour Party’s economic programme is simply a more caring version of modern economic orthodoxy.

According to McDonnell, Labour wants to ‘build an economy that is radically fairer, radically more democratic, and radically more sustainable’. However, adopting the language of radicalism does not ensure that the specific economic policies proposed are genuinely ‘radical’, in the sense of going to the root of today’s economic problems.

Certainly Labour’s redistributionist policies are neither distinctive nor economically radical and transformative. Very few politicians, and none on the front benches of any party in parliament, will say they want a more unequal, less fair society. Redistribution in the midst of a long depression redistributes the hardship. Reducing taxes on the poor, an objective of every British government in living memory – though not always delivered – doesn’t inevitably increase spending, never mind boost the economy. Poorer people, just like richer people, cannot be expected to spend all or even any extra money they get from redistributionist policies. The poor are as likely as anyone else to use extra income to pay off some of their debts, or to save some for the future.

Policies directed towards boosting economic growth are more appropriate than redistribution for depressed times. But aspiring to growth and achieving it are different things. Everyone supports industrial renewal assisted by varying levels of public intervention. Even many right-wing economic liberals favour state intervention to support capitalism. The left’s most famous bête noir, neoliberal Friedrich Hayek, supported a state central bank, regulation of the financial sector, and public research and development, and he expressed sympathy for intervention to curb monopoly power. So there is nothing radical about state intervention per se.

What matters about state intervention is whether it acts to sustain the economic status quo or to disrupt it. We live in times where for at least three decades the predominant bipartisan impulse has been to hang on to what exists. This doesn’t imply people in authority are all rosy-eyed enthusiasts about the current state of the economy. But it does mean that they see the immediate priority as guarding against further deterioration out of a fear of greater instability. In this, Corbyn’s Labour is at one with the Tories.

This is the economic policy expression of Hilaire Belloc’s line, ‘Always keep a-hold of Nurse for fear of finding something worse’. However, this cautionary tale for young children condemns an economy to the very end they say they want to avoid. Depressed economies do not fix themselves. The goal of stability is an accelerant of instability.

Preservative policies act to entrench stagnation and deepen decay. What is needed is not economic stabilisation but disruption. We need to get rid of the zombie aspects of the economy that are bringing congestion and impeding investment, transformation and a resumption of growth.

The question for bringing the British, and other Western economies, out of their prolonged slump, is should the state seek to save or abandon struggling low-productivity businesses, industries and sectors? So far, the unanimous answer from past Labour, Conservative-Liberal and Tory governments has been ‘save them’. They might not always have succeeded. They might have even had the gall to blame EU state-aid rules for not being able to do enough to save them. On this fundamental question Corbynomics gives exactly the same answer.

Yet destruction of the decrepit is required to make way for new sectors and expanding businesses that can revive productivity growth. Without this we won’t be able to provide secure, well-paying jobs for everyone who wants one. Corbynite Labour’s proposals so far are much more in the direction of sustaining what exists than shaking things up. For instance, it now wants to preserve the status quo in trade relations with the protectionist EU, though still claiming to want lower barriers to trade. This non-radical, conformist and non-extreme incongruity flows through its trade policy: Labour says it is both against ‘protectionism’ and simultaneously favours ‘protection’ and ‘safeguards’ for British businesses (9).

Some of Labour’s sympathetic leftist critics may agree that the 2017 manifesto was not radical. However, they attribute this either to the latent power of right-wing forces within the Labour Party, or to a desire to assuage those concerned about Corbyn’s electability. With the passing of time, and a bit more pressure and motivation, these critical supporters assure that the programme will go much further.

But when many left-wing sympathisers suggest how to make the earlier proposals more concrete, the problems created become more explicit. Take the famous ‘Preston model’ for how Labour’s national economic programme could evolve. In 2018, consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), in association with the think-tank Demos, named Preston in Lancashire as Britain’s ‘most improved city’. With a Labour-run council and 140,000 inhabitants, Preston is often held up as a model of Corbynomics in action.

Labour supporters see what has happened in Preston as a model of localist ‘municipal socialism’, by pushing local procurement and trade. Starting several years before Corbyn became party leader, Preston City Council sought to ensure that more money was spent locally, with local contractors and suppliers, rather than further afield. The pool they drew from included local-authority budgets and those of other centrally funded local ‘anchor institutions’, such as hospitals, the police, the housing association, the University of Central Lancashire and other colleges.

Partly as a result of this council encouragement, by 2017 six of these anchor institutions spent 18 per cent of their budget in Preston, compared with five per cent in 2013. In cash terms, this meant an extra £75million being spent in the city – around £530 per citizen. The share of their spending in wider Lancashire as a whole doubled to almost four-fifths. Labour councillor Matthew Brown reassured The Economist that this initiative required no extra money, nor new legislation. ‘It’s about collaboration’, he explained, ‘You have to be clever in austerity.’

Labour’s economic pledges merely confirm it seems more attracted to protecting the British economy than transforming it

Brown has presented what has been happening in Preston as part of a broader ‘post-capitalist’ response (10). Corbynite Labour has seized upon Preston as an example of what it could do nationally. All public-sector purchasing, including central government’s £200billion in procurement spending, could be used to buy more goods and services locally.

But what would this change from now? Most of this spending is already going towards propping up British businesses. Okay, some of it ‘leaks out’ to foreign suppliers, but if Britain under Labour blocks foreign businesses from tendering for public contracts, there will be downsides, too. Public costs might rise if more efficient foreign suppliers are excluded, resulting in less money for other local suppliers. Overseas governments will also likely retaliate. This will reduce sales by any more efficient British businesses to foreign public sectors. The net effect is likely to be tiny.

Moreover, no, or very little, new value is added to a national economy when items are purchased locally rather than regionally or nationally. All it means is that part of the existing produced value collected through local and national taxes might be spent with a different local supplier. This is not just national protectionism, but municipal protectionism.

Also, because it relies on the use of budgeted public expenditure, it is a practice that is most relevant to areas of the country where private-sector activities have fallen away, leaving a relatively greater dependence on state spending. Spreading this money out geographically means a central government compensating where the economy is weakest rather than playing to national strengths.

More importantly, this brings us back to the flawed focus on demand. Deficient demand is not the significant economic challenge, especially when debt is so easy and cheap to come by. Protecting local business in this way actually exacerbates the real problem of businesses being stuck in their low productivity trap. An extension of municipal protectionism will continue to mollycoddle anaemic businesses as they are now, propping up the zombie economy. Weaker businesses will be subsidised and stronger ones might lose out in foreign markets.

Locally informed economic policy is great when it engages people better in the goal of wider economic revival. But the local protectionism of the Preston model is a barrier to local (and also national and international) economic renewal. You can describe this any way you want, but to declare it as ‘post-capitalist’ reveals a rather odd interpretation of capitalism.

The only way to improve living standards without piling up debt is through productivity growth: workers producing more in the same time because of investment in better technology and tools. It is telling that in the same PwC survey ranking Preston as the ‘most improved’ city, it still ranked 14th in the national list, behind ‘high’ achievers like Aberdeen, Milton Keynes and Coventry. Preston’s overall ranking indicates the lack of evidence that extra localised public spending has done anything to help boost local productivity levels above the national average.

Conclusion

Adding flesh to the bones of Labour’s economic pledges merely confirms that it seems more attracted to protecting the British economy than transforming it. Despite the Corbyn Labour Party’s aspirations for a fairer, better world, its present package of policies does little more than preserve a broken economy. And by sustaining low-productivity businesses it is impeding the precondition of investment in higher productivity replacements.

Labour conforms to personalising the dire state of British capitalism. By going along with identifying the richest one per cent as the prime source of our economic problems, Labour evades the question of which group has done most to obstruct economic renewal. This responsibility rests not with the richest people, but with the political class that has been peddling policies that favour the status quo.

Politicians have cut themselves off from their electorates and have been acting in ways they think suits their own interests. They praise democracy as a wonderful liberal idea – as long as it doesn’t impinge on what they want to do. Without a return to popular accountability it is hard to envisage how to get policies that can help revive the economic growth needed for addressing pressing social and economic challenges.

The Corbyn-led Labour Party isn’t helping and in fact has become part of the problem. It has already gone far down the undemocratic road, openly expressing its uneasiness with how British people have been voting. This has culminated in Labour now ignoring its own 2017 manifesto commitment to accept the referendum decision to leave the EU.

This stance is further evidence that Corbynite Labour is retrograde compared even to 1970s labourism. Many Labour Party parliamentarians in the past echoed the Tony Benn position of opposing European institutions as inherently undemocratic. Many of the same, Corbyn included, are now advocating Labour’s effective brush-off to British democracy. We should worry much more about a Corbyn government than leaving the EU, both for economic and for democratic reasons.

Phil Mullan’s latest book, Creative Destruction: How to Start an Economic Renaissance, is published by Policy Press.

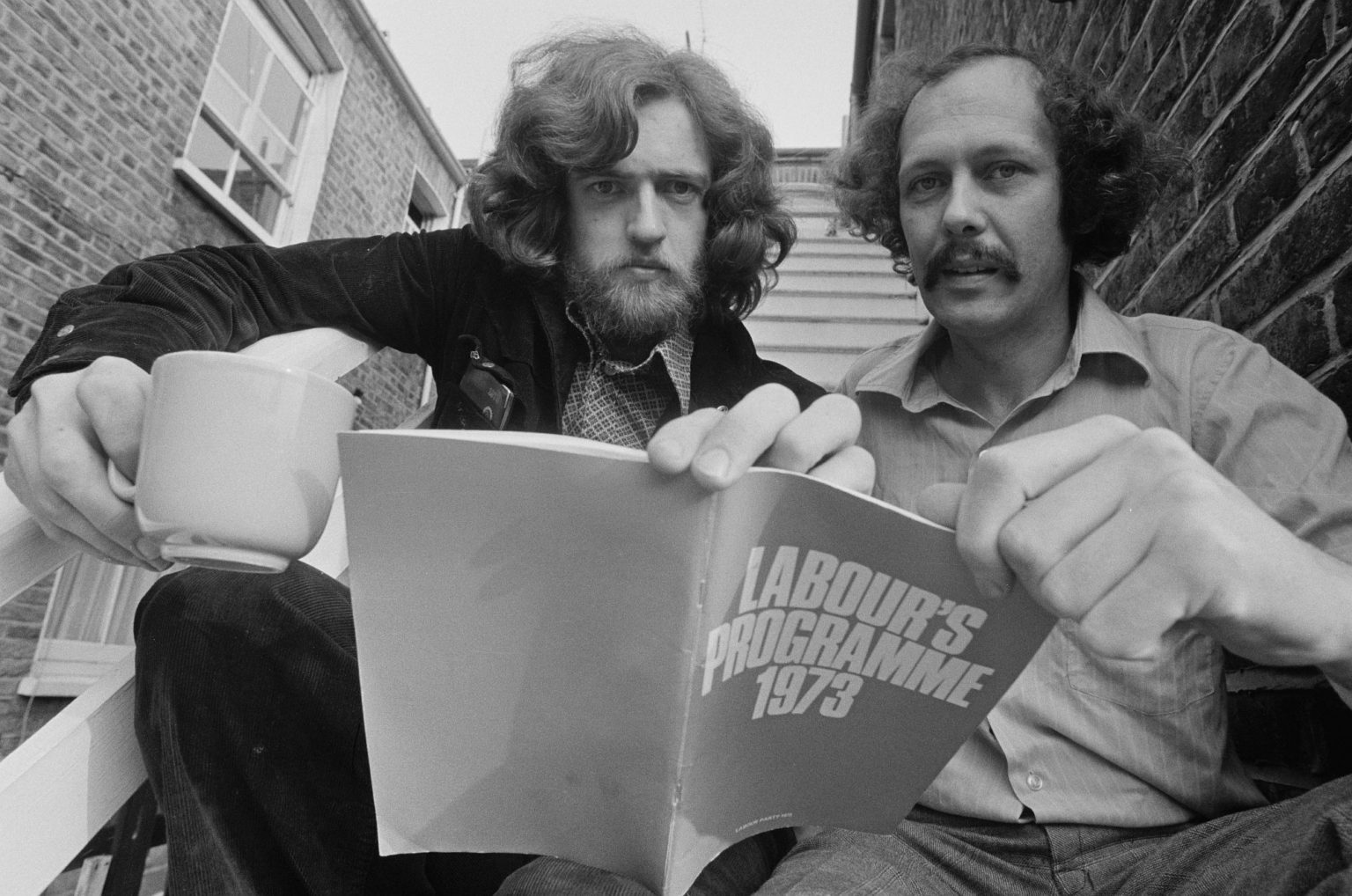

Pictures by: Getty Images

(1) Corbynism: A Critical Approach, by Matt Bolton and Frederick Harry Pitts, Society Now, 2018, p96

(2) Economics for the Many,(ed) John McDonnell, Verso, 2018 pVII

(3) ‘The dog and the frisbee’, Andrew Haldane. Speech delivered at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Jackson Hole Symposium, Wyoming, 31 August 2012

(4) ‘The Corbyn Project: Public Capital and Labour’s New Deal’, by Robin Blackburn, in New Left Review 111, May-June 2018, p5

(5) ‘Better Models of Business Ownership’, by Rob Calvert Jump, in Economics for the Many, (ed) John McDonnell, Verso, 2018, p88

(6) ‘Better Models of Business Ownership’, by Rob Calvert Jump, in Economics for the Many, (ed) John McDonnell, Verso, 2018, p89

(7) See ‘The British corporate welfare state: public provision for private businesses’, by Kevin Farnsworth, Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute Paper 24, July 2015

(8) ‘Labour’s Fiscal Credibility Rule in Context’, by Simon Wren-Lewis, in Economics for the Many, (ed) John McDonnell, Verso, 2018, p21

(9) ‘Fair, Open and Progressive’, by Barry Gardiner, in Economics for the Many, (ed) John McDonnell, Verso, 2018, p 62

(10) ‘A New Urban Economic System’, by Matthew Brown in Economics for the Many, (ed) John McDonnell, Verso, 2018, p140

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.