The white-black theatre director

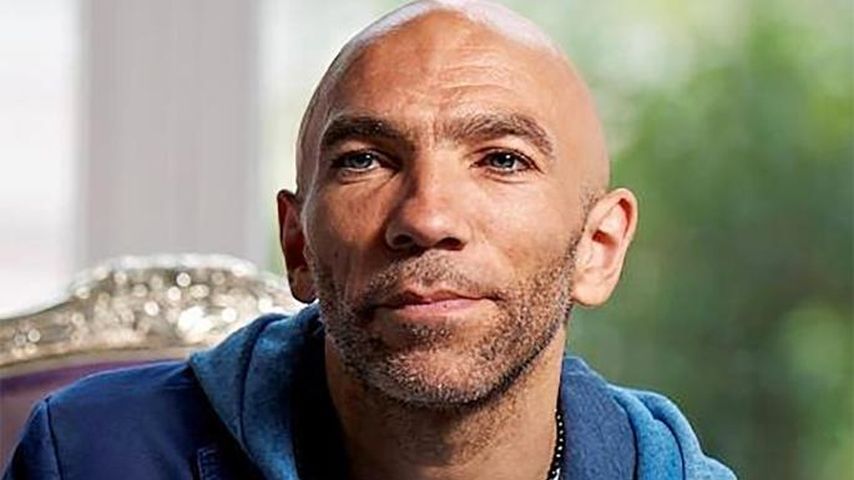

The story of Anthony Ekundayo Lennon shines a light on the paradoxes of identity politics.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It’s hard not to feel sorry for Anthony Ekundayo Lennon. Despite having won awards as a ‘theatre practitioner of colour’ and having been assistant director on Britain’s first all-black production of Guys and Dolls, it turns out he is not actually black at all. The Sunday Times uncovered Lennon’s secret past and outed him as that most loathed of all beings: a white man.

Lennon’s story has now been publicly dissected, his motivations questioned, his biography held up for scrutiny. We have been told that he dropped the middle name chosen by his parents, David, in favour of the Nigerian name Ekundayo, when he began exploring his identity. Imagine just for one moment that a transgender person was discussed in this way – the sin of deadnaming warrants instant condemnation.

Lennon seems to have made little secret about his identity. Previously, in a BBC documentary, he said that not only are his parents white, but so are their parents, and their parents before them. His black friends and colleagues expressed disbelief. ‘I thought you were half-caste,’ says one.

Another accuses Lennon of watching and copying black people. The BBC would sooner go bust than feature someone saying ‘half-caste’ today and the charge of ‘cultural appropriation’ has replaced the less incendiary ‘watching and copying’. But back in 1990, it seems people could ask what makes someone black, and do so on television, without prompting a national meltdown.

Comparisons have been drawn between Lennon and Rachel Dolezal, who, in 2015, was similarly outed for whiteness. Lennon appears – so far – to have been spared the vitriol heaped upon Dolezal. One key difference is that Lennon didn’t alter his appearance, his naturally dark complexion meant that he was assumed to be mixed race and experienced racism as a result. In 2012, he claimed to have been through ‘the struggles of a black man, a black actor’. Whereas Dolezal pretended to be something she was not, Lennon became what others thought he was.

Lennon has described himself as a ‘mixed heritage individual’, arguing that ‘racial identity is not always black and white’ and that ‘everybody on the planet is African. It’s your choice as to whether you accept it.’ Dolezal has claimed ‘the idea of race is a lie’. ‘What I believe about race is that race is not real’, she said, ‘it’s not a biological reality. It’s a hierarchical system that was created to leverage power and privilege between different groups of people.’

For Lennon and Dolezal, their feelings about their identity trump their racial categorisation. ‘For me’, Dolezal said, ‘how I feel is more powerful than how I was born. I mean that not in the sense of having some easy way out. This has been a lifelong journey… if somebody asked me how I identify, I identify as black. Nothing about whiteness describes who I am.’ Lennon says, ‘My genes are white but I am black’.

Swap the words white and black for man and woman and Dolezal and Lennon would be celebrated for bravery and for challenging convention. They would be gracing the front covers of glossy magazines and be getting nominated for awards rather than having them rescinded. Today, the idea that sex is an arbitrary assertion by a doctor and contributes nothing to your true gender identity, that how you feel is more important than what you were born as, that your genes might be male but you are nonetheless a woman, becomes more accepted each day.

Yet, bizarrely, when it comes to race, none of this applies. As Lennon and Dolezal prove, it’s not acceptable to talk of having been assigned the wrong race at birth but knowing, deep down, that you always had a different ethnicity.

The scientific consensus for much of the past half-century backs up Dolezal’s assertions that race is meaningless as a biological category. We know, for example, that more genetic variation exists within rather than between populations and that human populations have emerged from common ancestors and have since merged into each other, meaning that distinctions between races are arbitrary.

No serious scientists make the same arguments in relation to sex. Humans, as mammals, reproduce sexually; a female egg is fertilised by male sperm. Male and female are two distinct categories in all mammals. People exist as a biological reality but a biological reality that interacts with – and is in turn shaped by – society. Science might tell us about the differences between people, but the significance of these differences is determined by society.

Today’s identity politics means that the biologically arbitrary differences of race are seen as rigid and entrenched. The old slogan ‘one race, the human race’ is considered by many radicals to be a racist denial of difference and privilege. Now, hairstyles, music and clothes are all firmly demarcated as belonging to one racial group or another and no transgressions are permitted. At the same time, the scientific reality of sex differences is seen as a random act of violence that should count for nothing. How people identify, how they dress and look, is all that counts in defining what makes a man and a woman.

The upshot of all this is not a looser, more liberal view of what men and women can be, but the opposite: a more conservative division between people. Denying the rigidity of racial divisions and the flexibility of gender divisions are both crimes in the eyes of today’s identitarians. Dolezal was accused of being a ‘race faker’.

Dolezal and Lennon have, rightly, been accused of taking money and platforms that were specifically designated for black people. Doing so was dishonest and immoral. But it also raises questions about such attempts at positive discrimination: what defines someone as black, Asian or minority-ethnic, and are all BAME people equally disadvantaged?

However, at the same time, I’d rather argue against the continued existence of all-women shortlists for jobs or political posts than see them made meaningless by permitting entry to anyone who self-identifies as a woman.

Dolezal and Lennon have been criticised because, unlike gender, racial moving is a one-way street: white people can pass as black, or mixed heritage, but not the other way round. Georgina Lawton, writing in the Guardian, argues that ‘the conversation around racial fluidity continues to be hijacked by a privileged minority, white or white-passing people opting for a performative, monolithic type of blackness that fails to acknowledge the complexities of being a real-life person of colour’.

But perhaps a genuine conversation today needs to permit questioning the insistence that privilege begins and ends with race and gender. We need a conversation that allows us to move beyond rigid ideas of what it means to be black or white, man or woman, and to focus on what we have in common rather than what divides us.

Joanna Williams is associate editor at spiked. Her new book, Women vs Feminism: Why We All Need Liberating from the Gender Wars, is out now.

Picture by: YouTube

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.