Ulrich Beck and the turn against modernity

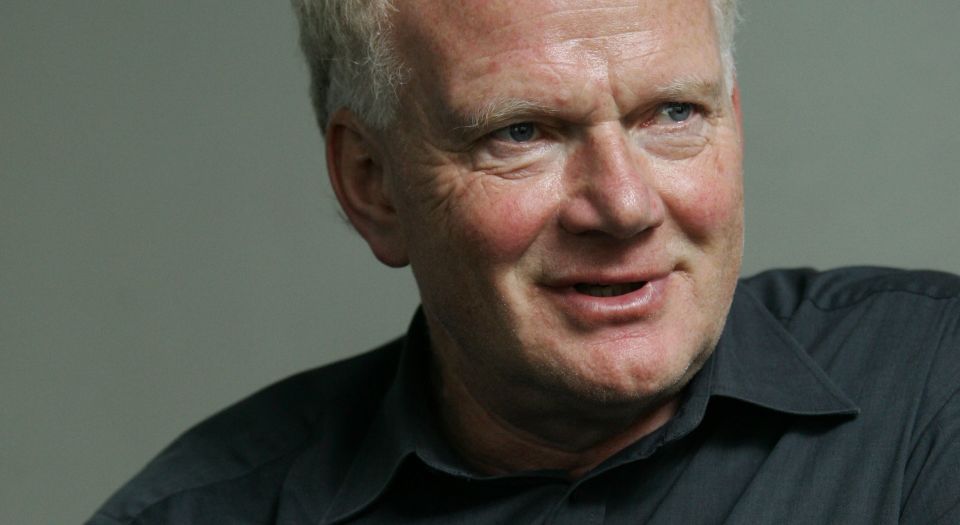

The late sociologist encapsulated the fears of our era.

German sociologist Ulrich Beck, who theorised the ‘risk society’, died earlier this month at the age of 70.

Sociology, especially German sociology, suffers because Karl Marx’s theory of society was so compelling, and much of what follows after is a debate with Marx. Before Beck made his name, Max Weber and then Jürgen Habermas grappled with Marx’s account of the working classes as the subject of history, whose life conditions gave them the motive to abolish the unplanned society of mutual hostility of the market. Habermas thought that Marx’s ‘collective subject’ was an impossibility, and that the best we could hope for was an open-ended conversation, carefully moderated by rules of engagement – which shows some similarity to the ‘managed democracy’ that the allies put in place in Germany after the war.

Younger than Habermas, Beck’s sociology drew on themes suggested by the growing environmental movement in Germany. His first book, Soziologie und Praxis (1982), was not so different from much that was being published at the time, but in his next and best-known book, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (1986 in Germany), Beck made a big impact.

The core idea was that the old monocultural, industrial modernity was giving way to a new one that was much more complicated, full of unintended consequences, in which uncertainty would grow exponentially. He was thinking first of pollution, a problem that was highlighted by the Green Party. Thinking on the problem, Beck argued that if the unplanned and unintended consequences of industrialisation were great, then the hope of modernity – that society could be directed and that growth would overcome the chaos of nature – would have to fail. He thought that the unintended consequences would grow at a faster rate than the intended ones, and our hopes of mastering nature and society would only lead to more uncertainty. He called this new modernity ‘reflexive’, in that the impact of actions would rebound upon us, interfering with our original aspirations. Unintended consequences were ‘risks’, dangers that grew exponentially as industrial society developed.

The old politics was an argument between capital and labour over the share of industrial output. But with risks growing all the time, argued Beck, the new issues were not over the divisions of industrial gain, but rather over the question of whether you are for or against the runaway industrial juggernaut that was putting us all at risk. The Marxist dream of a single agent of history was as redundant as the industrialist’s dream of progress, in Beck’s telling. No single mind could hope to encapsulate the future, because it was radically uncertain, and uncertainty was growing all the time, much faster than our attempts to make sense of it.

There was something very pessimistic about Beck’s conclusions, though he always came across as an optimistic and cheerful man. He did say that though grand political projects were dinosaurs of the first modernity, the new reflexive modernity had not just room but also a great demand for what he called micro-politics, of which the model might be a campaign against a new road or over immigrants’ rights. What was not possible, he thought, was a singular vision of the future, as he argued in the book that he was writing when he died, to be published as The Metamorphosis of the World.

Beck was a very inventive and speculative thinker whose great advantage was his willingness to try to give expression to new ideas, pulling them out of the ether of modern life. He was very sharp on the way that, so often, we carried on using the old ideas of the past, unaware that these were already drained of all real meaning. These he called ‘zombie categories’. But too often he inflated an emerging trend into an already realised fact. His later books read like bullet points on a whiteboard, with the substantiation to be sketched in at some later date – one that never came.

Turning to the question of international relations, and especially the emergence of the European Union as a new force, Beck was carried away by the post-national thinking of the coterie of conference-attending academics and Eurocrats. He dismissed as ‘methodological nationalism’ analyses that saw nations as real, insisting instead that we were already living in a globalised world where nations were merely zombies. He only saw backward-looking ethnocentrism in the nation state, and was unmoved by the disappearance of democracy that the post-national EU offered.

When the EU proposed to supersede national assemblies in its constitution of 2005, Beck backed it, as did all the mainstream statesmen and commentators. But the voters rejected it in referenda across the continent. Afterwards, an unbowed Beck insisted that the constitution he had endorsed the week before was fatally flawed, being just another kind of modernist nation state that was bound to fail. Last year he published German Europe, a sharp critique of what he says is a German-dominated Europe, incorporating many of the Eurosceptic themes that he had earlier dismissed. But even here, his real meaning is that Germany ought to be restrained by the European post-national institutions rather than overawing them.

At the core of Beck’s thinking was the limitations upon human action. Radical uncertainty would always undo the pretensions of those Promethean ideas of the first modernity. To take control of society and drive it forward was not just foolish, but dangerous, he said, creating ever-greater risks and dangers. His ideas took succour from the growing tide of anxiety about industry and social change, and made it into a virtue. Though his is the prize for first expressing the idea of the ‘risk society’, he failed to criticise the sentiments behind it, saving all his scepticism for the ‘old modernity’ and the nation state.

The ideas that he promoted elevated fear and risk, even as positive forces for social solidarity. But everyone can see that fear and an exaggerated sense of risk do not lead to positive movements, but only to reaction and the scapegoating of those who embody those risks, whether they are foreigners or industrial workers. Fear was his metier, and it paralysed his ability to understand the world. All his creative powers were disrupted by the uncertainty that he saw growing ever larger in the world. Beck died this month, but his thinking was always recoiling from life.

James Heartfield is author of The European Union and the End of Politics, published by ZER0 Books.

Picture: Wikimedia Commons

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.