Labour’s attack on the right to trial by jury

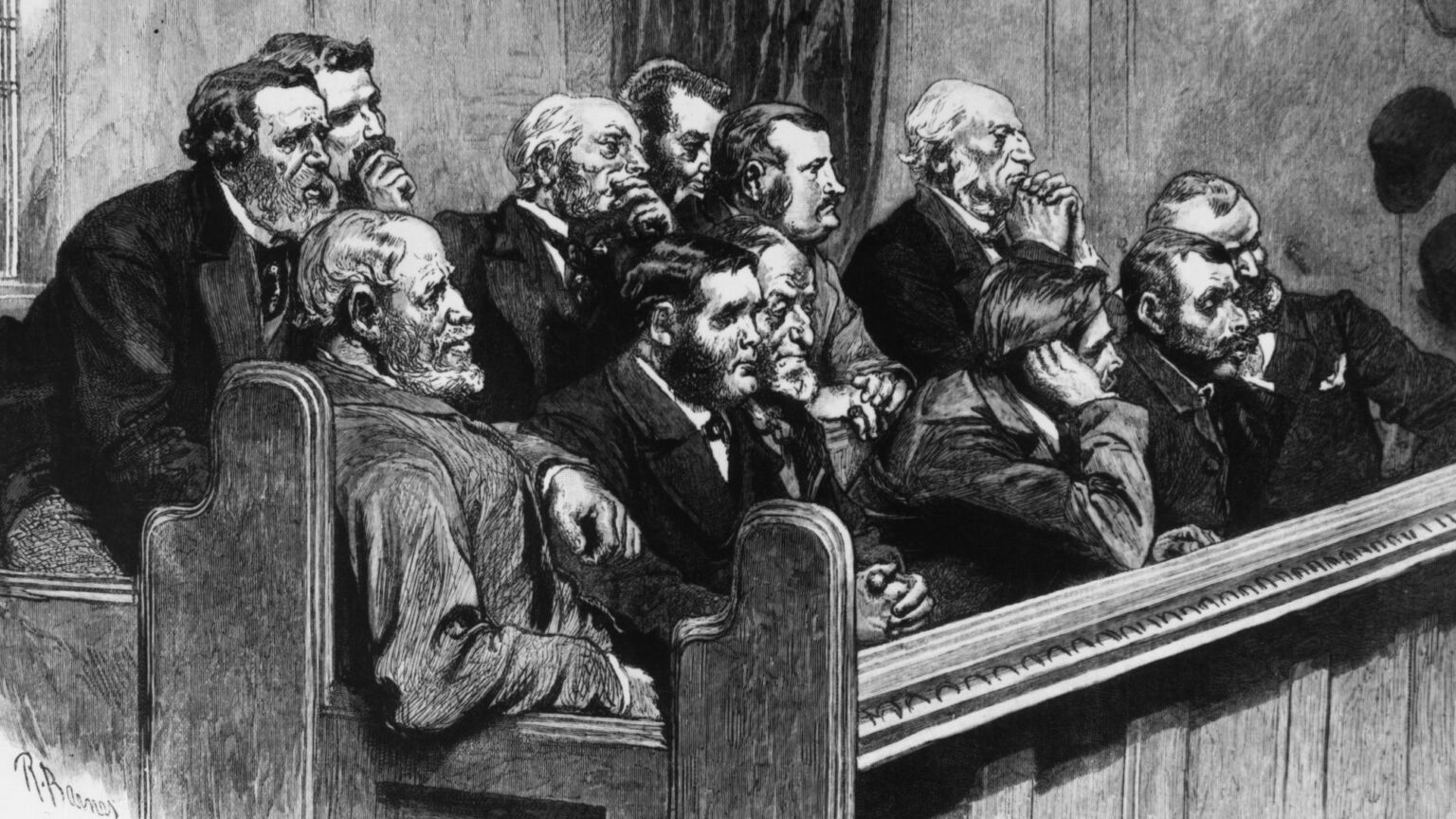

Jurors are the ultimate protectors of our liberty. No wonder the political class hates them.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

In 1670, two Quakers – William Penn and William Mead – were put on trial in London. They were charged with unlawful assembly for preaching to a crowd in Gracechurch Street, after the recently passed Conventicle Act banned religious meetings of more than five people outside of the Church of England.

The jury, led by Edward Bushell, refused to convict the defendants, despite strong pressure from the judge. The judge was furious and locked the jurors up without food and water in an attempt to change their verdict. But the jury held firm and acquitted Penn and Mead. In response, the judge imprisoned the jury as punishment for their verdict.

Bushell and his fellow jurors challenged their imprisonment, claiming it was unlawful. The Court of Common Pleas agreed with Bushell, finding that the jury was independent and had a right to return any verdict that was in accordance with the law. This is known as Bushell’s Case. Today, there is a plaque dedicated to it on the wall of the Old Bailey in London. The case is featured in any decent textbook on the English legal system.

Juries have played an essential role enforcing public morals in our courts, ever since Bushell’s courageous fightback. They played a powerful role in combatting unjust laws surrounding slavery, often refusing to punish those who had helped free slaves. This refusal to convict defendants accused of breaking an unjust law became known as ‘jury nullification’.

This has continued to the present day. In 1985, a British jury acquitted Clive Ponting, a senior civil servant in the Ministry of Defence. Ponting leaked classified documents to opposition Labour MP Tam Dalyell that contradicted the Thatcher government’s account of the sinking of the Argentine warship, General Belgrano, during the Falklands War. He had been charged under the Official Secrets Act. The judge said he had no defence. The jury disagreed.

This is why we should always be wary of calls to limit trial by jury. Juries are the final bastion of public morality in our legal system. They allow the public to be the arbiters of how the black letter of the law is applied. Lord Devlin famously described the jury system as ‘the lamp that shows freedom lives’.

Calls to dim this lamp have been made often in recent years. Serious fraud trials are said to be too complicated for the public to understand. In rape trials, jurors are presumed to be too bigoted and backward to fairly assess the evidence. Time and again, the political class has sought to sacrifice trial by jury for the sake of greater efficiency in the justice system.

Now it’s the turn of Keir Starmer’s Labour government. UK courts minister Sarah Sackman said last month that the ‘acute scale’ of the post-pandemic courts backlog means that the time for ‘intermediate courts’ has ‘probably come’. This proposal, currently under review by Sir Brian Leveson, a former judge on the Court of Appeal, would create courts where a judge and two magistrates would preside over ‘serious cases’ that would otherwise go before a jury. Sackman also said that less serious ‘either way’ offences, which can be tried in either a crown court or a magistrates’ court, could also be heard in these intermediate courts. These either-way cases represent more than half of the nearly 80,000 cases waiting to be tried.

Giving up trial by jury on the grounds of cost-effectiveness or speed would be a false economy, however. It would likely give rise to a tide of appeals, with defendants arguing that they had been denied their fundamental rights. There would be a challenge under Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees the right to a fair trial. All of this would probably delay the resolution of the cases within the backlog even further.

Still, the practical arguments are not really the point. Conceding our right to jury trial would set a terrifying precedent. It would suggest that our fundamental rights can be brushed aside in favour of efficiency.

There are other ways to clear the backlog. We should be looking at diverting more cases away from the criminal-justice system. We could experiment with US-style drug courts, which provide more therapeutic interventions for those repeatedly charged with low-level drug offending. We could divert more offenders with clear mental-health issues away from the criminal courts. We should invite the Crown Prosecution Service to carefully review the cases within the backlog to make sure that all of them justify prosecution. There is a good chance that many of them could be dealt with through out-of-court disposals, such as cautions or so-called community resolutions.

What we cannot do is continue to entertain these attacks on juries. You only have to spend a day in a modern courtroom to see the common sense that juries bring to an often arcane and impenetrable system. A trial by magistrates is no substitute. We must defend the jury trial at all costs.

Luke Gittos is a spiked columnist and author. His most recent book is Human Rights – Illusory Freedom: Why We Should Repeal the Human Rights Act, which is published by Zero Books. Order it here.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.