Why Prevent failed David Amess – and will fail again

How did counter-extremism officials allow Islamist killer Ali Harbi Ali to slip through the net?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

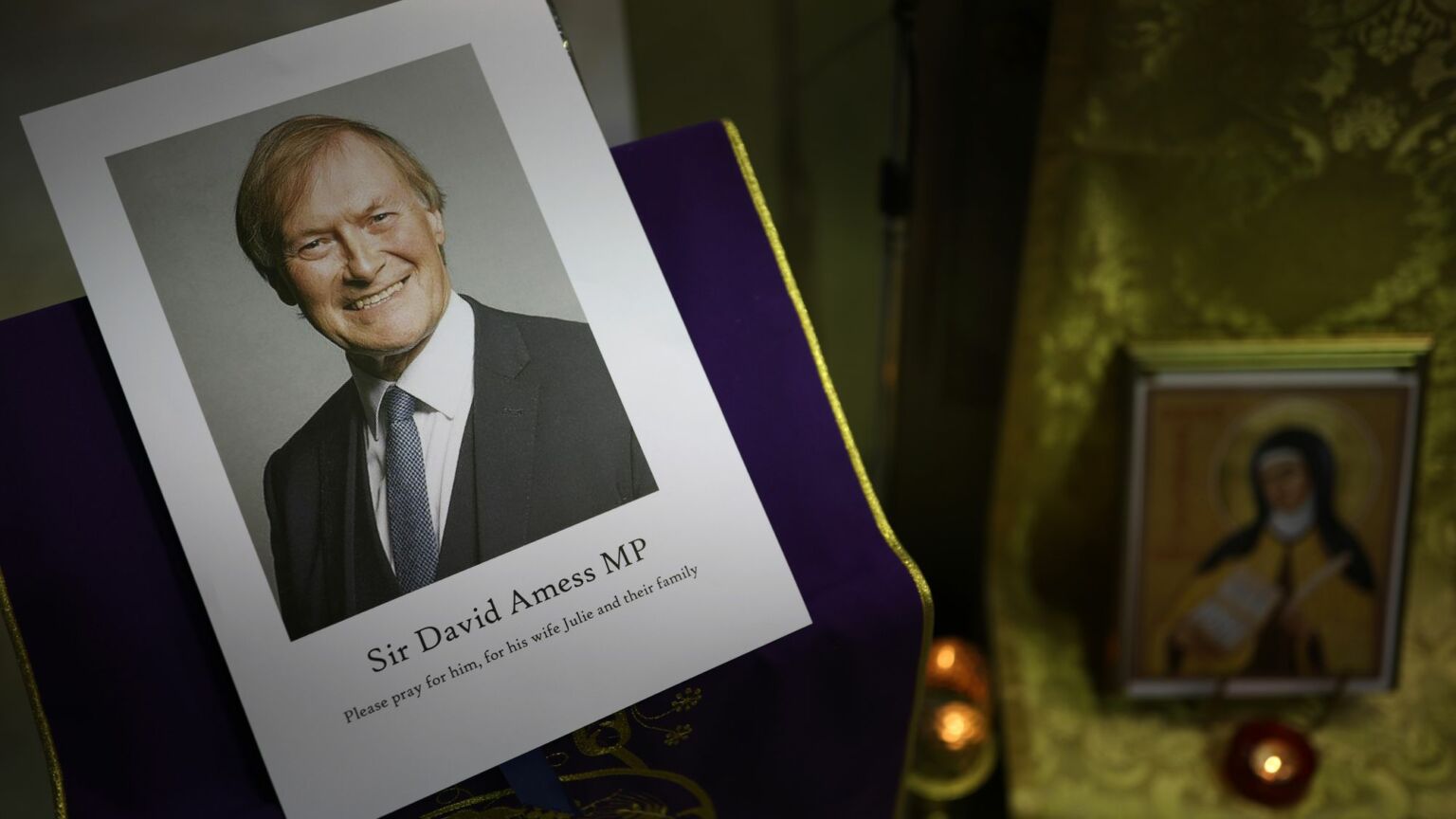

After the Islamist terrorist, Ali Harbi Ali, murdered Tory MP David Amess in October 2021, it quickly emerged that Ali had taken part in Prevent, the UK government’s counter-extremism programme. This week, the Home Office finally published its ‘learning review’ into Prevent’s handling of Ali’s case, three years after it was circulated internally. Not even the redactions or the bureaucrat’s heavy hand can disguise the glaring failures that let Ali slip through the net.

The report describes what are often indefensible failings in a dry, bureaucratic language and a tone of gentle disapproval. Decisions about managing the risk Ali posed were ‘sub-optimal’, it says. Prevent’s sole face-to-face intervention with Ali was ‘problematic’. The approach taken by officials to spot and stop tomorrow’s terrorists was ‘questionable’. Yet it is still impossible to forget when reading the report that what is being outlined here is the state’s inability to contain murderous extremism.

What are the facts? Ali was referred to the Prevent programme in 2014 by his school. This once ambitious student with a bright future ahead of him had changed so considerably in terms of his behaviour, demeanour and performance that teachers feared he was becoming radicalised. He started wearing traditional Islamic clothing. He became withdrawn and started to express extreme views. His schoolwork took a nosedive.

When he was first assessed by Prevent officials, his risk of harm was considered so great that he was referred to Channel – the part of the Prevent programme that determines and manages interventions for those not filtered out by the initial screening process. To give this context, only seven per cent of Prevent referrals in 2024 resulted in Channel interventions. Despite the fact that Ali crossed this high bar, the management of his risk was seriously deficient in several important respects.

Most notably, Ali was exited from the Prevent programme far too quickly. By early 2015, the panel of Channel officials overseeing him concluded he was ‘low risk’, and a few months later he was out of the programme. His school did not receive any feedback from the process and was not involved further after his initial referral. That meant an important line of communication, which might have made caseworkers aware that Ali was still a risk, was severed.

According to the report, one of the main tools used by Prevent practitioners, the ‘vulnerability assessment framework’ (VAF), was of little value in accurately assessing Ali’s risk. Filling out his VAF form was merely a ‘check-box exercise’, which was no help in interrogating or reacting to any changes in his behaviour or attitudes over time. What’s more, the reviewer suggests that the VAF’s criteria for measuring someone’s risk of radicalisation is outdated.

Still, even if officials had the right tools at their disposal, it is clear from the review that it was not obvious who should have been making decisions about Ali – the police or Home Office officials. Responsibilities were ‘blurred’, it says. Both bodies were involved in Ali’s Channel panel, which could have authorised further interventions.

Only one ‘intervention provider’ ever met with Ali, and this was on just one occasion in January 2015, in a McDonald’s. Even then, only one of two required activities was completed. There was confusion about what the precise objective of the intervention was – the intervention provider was only briefed orally. There is no evidence of any risk assessments or written follow-up reports of what happened during the encounter. There seemed to be no communication between the person giving the intervention and either the police or the rest of the Channel personnel, who should have been overseeing Ali’s case.

The independent reviewer reassures us that such failures could not happen again, as reforms have been made to Prevent since Ali’s case. This is to put too much weight on the correct following of processes rather than actual outcomes. In Ali’s case, there clearly were many inexcusable and elementary failures in risk management that should never have happened in the first place. Basic steps were clearly missed. But a focus on process is a cultural disability that has taken root across state agencies, usually at the expense of the intuition, scepticism and professional curiosity that’s needed for dealing with complex threats.

The review wearily cheers all the ways in which the Prevent strategy has supposedly improved since its ‘sub-optimal’ encounter with Ali. That will be scant comfort to the relatives of David Amess. Or indeed the many other victims of killers who have slipped through Prevent’s cracks – most notably, Axel Rudakubana, the Southport murderer, who was referred to the scheme three times, once in 2019 and twice in 2021.

There are several other striking things about this independent review. The reviewer did not interview the key players involved. He relied solely on logs and emails, provided by police and Home Office officials. I do not impugn his professionalism in any way, but his reliance for information on people who might have been implicated in the failure to contain Ali is less than ideal.

Moreover, the review was released internally on 8 February 2022, after Ali was charged and before he was convicted. As such, there are several references to the need to be mindful of not jeopardising the police investigation or the upcoming trial. It’s not clear whether this limited what material could be considered for the report.

Finally, the list of the review’s intended recipients reveals something worrying. It shows that two of the key players in our national counter-terrorism strategy, the head of Prevent Intervention Programmes and the head of Channel Improvement, were (at least at the time of the review) only ‘junior civil servants’. What does this say about the importance, or lack thereof, that the British state attaches to stopping terrorism?

Counter-terrorism is not easy work. No one in this awful scenario set out to fail David Amess and his loved ones. But it is clear that far more work is needed than what this latest review suggests. Insisting that lessons have been learnt is simply not good enough.

Ian Acheson is a former prison governor. He was also director of community safety at the Home Office.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.