Long-read

How schools are turning kids against their families

Activist teachers, politicised lessons and endless mental-health initiatives are subverting parents’ authority.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Education in the UK has become ever more politicised in recent years. Through the curriculum and beyond, our schools are being used to inculcate children with values that may run directly counter to those of their family and community.

As I explore in a new report published this week – Teachers or Parents: Who Is Responsible for Raising the Next Generation? – the politicisation of education has taken three main forms.

First, new subjects have been added into the school curriculum that are inherently political in nature. For example, relationships and sex education (RSE) lessons cover contested concepts like gender identity and the nature of intimate relationships, while so-called citizenship classes look to cultivate particular attitudes to the nation and the environment.

Second, new politicised content has been introduced into more traditional academic subjects. Geography focusses on sustainability and environmentalism, literature becomes a vehicle for exploring attitudes towards race and gender, and history centres the sins of Britain’s past.

Third, pupils now pick up messages outside of timetabled lessons through assemblies with guest speakers, charity days and policies around behaviour and uniform. This ‘extra’ or ‘hidden’ curriculum has become fertile ground for activist-teachers.

In May 2024, in one of its final acts in office, the Conservative government announced new guidance for the teaching of RSE. Children were not to be taught about sex before the age of nine and contested ideas about gender identity were not to be taught as facts. This was an important first step towards altering a curriculum that had come to be perceived as overly sexualised and highly politicised. In order to appreciate the concerns of parents, and the lack of trust some have for teachers, we need to consider what schools were offering children prior to the most recent government intervention.

Previous statutory guidance on RSE had been introduced in 2019 and came into effect in 2021. The new curriculum was influenced by groups like Stonewall and the World Health Organisation and promoted a shift from sex to ‘sexuality’ education. Classes in secondary schools were to cover topics such as ‘consent, sexual exploitation, online abuse, grooming, coercion, harassment, rape, domestic abuse, forced marriage, honour-based violence and FGM’. In addition, schools were to teach children about gender identity and same-sex relationships. Children were taught not to assume that cis-gendered people, heterosexual relationships or the traditional family are, in any way, ‘normal’.

Significantly, while parents maintained the right to withdraw their children from sex education, they could not remove them from relationships classes. This not only made attendance in the most overtly politicised and contested lessons compulsory, it also effectively annulled the right to withdraw children from sex-education classes. When pupils looked at their school timetables, they saw RSE as a single subject. Withdrawing children from sex education while ensuring they attended mandatory relationships lessons would have required them to enter and leave a classroom at five-minute intervals.

In June 2022, members of the House of Lords complained that parents were being prevented from seeing what was being delivered to their children as part of RSE lessons. A few weeks later, Labour MP Rosie Duffield asked the then education secretary, Nadhim Zahawi, if he was disturbed by reports that headteachers were being prevented from sharing sex-education materials with parents.

These interventions reflected a growing concern among parents that children were being routinely exposed to material in RSE lessons that was sexually explicit, ideologically driven and scientifically inaccurate. These lessons sexualised children at an inappropriately young age and did so without parental knowledge or consent.

Last year, the New Social Covenant Unit compiled a dossier of evidence setting out the content of so-called sex-positive classes. They highlighted classroom activities that involve children ‘stepping away from heteronormative and monogamy-based assumptions’ in order to appreciate that ‘there are a variety of sexual preferences and practices’. This could involve children being taught about topics such as masturbation, oral sex, anal sex, fisting, rough sex, gender-queerness or polyamory, while the youngest children are expected to engage in activities such as drawing penises and making vulvas out of Play-Doh.

In October 2023, education secretary Gillian Keegan wrote to all schools in England stating that parents should be able to see what their children are being taught in RSE lessons, and that ‘schools must share teaching materials with parents’. This did little to alter the balance of power between school and home when it came to teaching children about relationships. Despite parents, journalists, think-tanks and MPs all having raised concerns about sexually graphic and age-inappropriate content being routinely used in school sex-education classes, another round of guidance was required in spring 2024.

RSE is not a traditional school subject. It has no disciplinary basis, no substantive body of knowledge and – although some make claims to the contrary – there is no such thing as a relationships ‘expert’. RSE is a means of imparting a particular set of values and political assumptions to a captive audience of school pupils. Although RSE lessons have changed, subject to further reviews by the new Labour government, the previous iteration of RSE caused harm. It caused harm to individual pupils who were subjected to inappropriate content that encouraged some to question their own gender identity and perhaps even seek medical interventions. And it also caused harm to collective parental authority in promoting the idea that the state, via teachers, is responsible for imparting attitudes and values about the most intimate aspects of life.

Citizenship education is another example of a political project that has been transformed into a school subject. It aims to steer children towards social-justice and environmental activism, and promote loyalty to transnational institutions. Citizenship classes often promote the values of global, rather than national, citizenship.

Citizenship education took off in the late 1990s, under Tony Blair’s Labour government, amid growing concern over young people not voting or otherwise engaging with public institutions. An advisory group on citizenship and democracy in schools was established and its final report was published in 1998. The ambitious aim was, ‘no less than a change in the political culture of this country both nationally and locally’. The report argued that all children needed citizenship lessons to tackle ‘political disconnection’.

In August 2002, the New Labour government made citizenship education compulsory for every student in English schools. A 2007 curriculum review led by Sir Keith Ajegbo expanded its remit. It set out a ‘vision’ that all schools should be ‘actively engaged in nurturing in pupils the skills to participate in an active and inclusive democracy, appreciating and understanding difference’. The connection between citizenship education, diversity and community cohesion was then formalised in the new national curriculum introduced into schools in 2008. The aim of citizenship classes was to enable all young people to become ‘responsible citizens who make a positive contribution to society’. In addition, a new theme, ‘identities and diversity: living together in the UK’ involved ‘appreciating that identities are complex’, ‘considering the connections between the UK, Europe and the rest of the world’ and ‘exploring the diverse national, regional, ethnic and religious cultures, groups and communities in the UK and the connections between them’ (1). Citizenship classes effectively became a catch-all solution to a variety of social and political problems.

In 2013, under the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, the citizenship curriculum was again re-drafted. Its new aim was to ‘foster pupils’ awareness and understanding of democracy, government and how laws are made and upheld’. It had a more national focus but remained an ill-defined subject that encompasses topics from personal financial planning to ‘how laws are shaped and enforced’. Such broad content, combined with a focus on practical, local activities, left classes open to the different political enthusiasms of individual schools and teachers.

Post-Brexit, several headteachers and representatives of professional associations signed an open letter to then education secretary Justine Greening calling for a renewed commitment to the teaching of RSE, citizenship and religion. Their focus was not national, but global citizenship. In other words, they envisaged citizenship education – elevating international commitments over an affinity with the nation state – as a direct challenge to the sentiments that were assumed to have led to British citizens to vote to leave the EU. In this way, citizenship classes distanced children from the values of their parents, an older generation that many held responsible for the vote for Brexit.

Citizenship classes are informed by a political agenda that is hidden behind a rhetoric of ‘values’. Children are encouraged to take on board a particular worldview without the capacity to disagree. This worldview is reinforced through more traditional academic subjects, such as geography, which promote anti-growth and anti-development ideas like sustainability (2).

The history curriculum has likewise become a means to steer children’s attitudes away from those of their parents and community. For over five decades, considerable effort has been invested in shifting the focus of the history curriculum from a chronological national story to an emphasis on the present. In 1972, the Schools History Project ‘launched a radically new content offer’, which ‘included topics strongly linked to present-day crises’, such as Northern Ireland and the Arab-Israeli conflict, as well as ‘world themes across time such as energy and medicine, and an emphasis on local history through the archaeology of the built and natural environment’ (3). This was, at least in part, a reaction to shifts in the academy that centred ‘black history, women’s history and attention to indigenous peoples that sought to transcend and critique colonial lenses’. This identitarian approach leaves history open to today’s critical race theory-inspired movements to ‘decolonise’ the curriculum.

In 2010, the Conservative government attempted to overhaul a history curriculum that had come to be seen as not just political but anti-British, too. Then education secretary Michael Gove pledged that ‘all pupils will learn our island story’ and went so far as to argue that ‘this trashing of our past has to stop’. His announcement was criticised by teachers, academics, teaching unions, historians and the presidents of learned societies, such as the Historical Association.

In 2021, research by the Universities of Oxford and Reading found that 87 per cent of UK secondary schools had made substantial changes to history teaching – not to emphasise a national story but to address issues of diversity. The reasons cited included ‘a sense of social justice, to better represent the nature of history and the stimulus of recent events’, a reference to the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. Seventy-two per cent of teachers claimed their classes covered the history of migration, while 80 per cent said they engaged pupils in a study of black and Asian British history. Most common was a focus on the postwar period, including the experiences of the ‘Windrush generation’, but many also reported teaching the black Tudors. Meanwhile, the UK’s biggest teaching union, the National Education Union, published a report urging the decolonisation of ‘every subject and every stage of the school curriculum’. It argued that every aspect of school life, from the design of school classrooms to the structure of their daily routines, has colonial roots.

Education is clearly being used by schools and teachers to promote a distinct set of values that may be at odds with those held by a pupil’s parents. Some educationalists see schooling as a means to bring about social change. On matters such as climate change or gender identity, children are expected to educate their parents and other adults, rather than the other way round.

At one primary school in Birmingham, children are co-opted into policing their classrooms and playgrounds. If a teacher misspeaks, pupils hold up brightly coloured posters highlighting the particular speech crime that has been committed. They are praised for shaming the teacher, compelling an apology and alerting fellow pupils to the incident. Each week, the two children who pursue this task most enthusiastically are rewarded with a certificate. In 2021, St Paul’s Girls’ School in London replaced the title ‘head girl’ with the more gender-neutral title, ‘head of school’. This sends a message to pupils and parents alike that the word ‘girl’ is outdated and offensive.

Politicised schooling moves education away from the transmission of traditional bodies of knowledge that connect children to their intellectual inheritance. Instead of education enabling a conversation between the generations, it now breaks with the legacy of the past. Instead of weaving a thread between children and their parents, grandparents, community and nation, it pushes political values that are often in stark contrast to the values of an older generation.

Alongside instructing pupils in beliefs and values that may run counter to the views of their parents, teachers encroach upon what was once assumed to be the responsibility of the family in relation to the health and wellbeing of their children. Take a typical rite of passage such as walking home from school alone. This is now actively discouraged by schools. Although independent travel is not illegal, many primary schools now have policies in place to prevent children leaving school alone or collecting younger siblings.

Kildwick Primary School in Yorkshire has a typical ‘walking home alone policy’. It states: ‘We believe that pupils in years 3, 4 and 5 should be still brought to and collected from school and this is our school policy. Therefore, as regards pupils in Year 6, we believe that you as parents need to decide whether your child is ready for the responsibility of walking to and from school alone.’

The school assumes responsibility for children below the age of 10 and makes a clear decision that they should not be allowed to walk home unaccompanied by a parent or other approved adult. For children above the age of 10, this responsibility lies with parents. However, the school does not simply leave parents to decide for themselves what is in their child’s best interests. It tells parents to ‘assess any risks associated with the route’ and to ‘work with your children to build up their independence while walking to school through route finding, road-safety skills and general awareness’.

By telling parents that younger children should not walk home unaccompanied and issuing guidance as to how such a decision for older children should be reached, the school positions itself, and not parents, as the experts in childhood. In other words, the act of telling parents that they should decide how their children get to and from school presumes that parents require advice and are subservient to the authority of teachers.

A similar dynamic can be seen around food. While many schools have canteens and provide lunches to children in the middle of the day, a substantial proportion of parents opt to give their children a packed lunch. Traditionally, what a child ate was considered to fall under the purview of parents. But increasingly, primary schools especially have ‘packed-lunch policies’ that set out which foods are permissible. St Winifred’s Catholic Primary School in London specifies strict guidelines for what lunch boxes must contain including, ‘at least one portion of fruit and one portion of vegetables every day’ and ‘dairy food such as milk, cheese, yoghurt, fromage frais or custard every day’. Chocolate, sweets and crisps are all prohibited. Parents at Wibsey Primary School in Bradford are informed that ‘staff on duty, midday supervisors and catering staff will monitor the contents of packed lunches’ with ‘serious concerns’ highlighted to the school’s senior management team.

School travel and lunch policies considerably expand the remit of teachers beyond education and into all aspects of childrearing. In the process, they undermine parents’ confidence in making decisions about their own children’s independence and safety. Parents are expected to defer to the advice of other adults who purport to be experts in their children.

Perhaps the most fundamental way in which schools assume expertise in and responsibility for areas other than education is in relation to child mental health. The Department for Education expects all schools to have a ‘whole school’ approach to promoting and supporting mental health and wellbeing. Among its ‘eight key principles’ are ‘curriculum teaching and learning to promote resilience and support social and emotional learning’, ‘identifying the need for and monitoring the impact of interventions’, ‘targeted support and appropriate referral’ and ‘working with parents and carers’. The DfE assumes that child mental health falls under the remit of teachers, whether that is through the curriculum or by offering targeted support to individual pupils identified as struggling, or working with families by suggesting ways for parents to support their children.

Commonly used school mental-health interventions include mindfulness, meditation and yoga. Government guidance suggests that teaching and learning should take place with a view to focussing on a child’s emotional responses in order to help them manage their ‘thoughts, feelings and behaviour’. This can be done through ‘emotional registers’, which involve asking children to observe and report on their feelings at various points throughout the school day. ‘Circle time’ can involve children in more open-ended discussion about their emotions with the teacher taking on the role of group therapist.

Clearly, teachers have a duty of care to seek help for children who are experiencing mental-health problems. But the routine use of whole-school interventions suggests that every child is considered to be in need of support and that it is the responsibility of schools, alongside or instead of parents, to care for a child’s mental health.

It seems to be assumed that families, far from providing a source of comfort to children, are in fact the source of emotional problems. In this way, teachers as experts in child development at best assume responsibility for children’s mental wellbeing in lieu of parents. At worst, they actively undermine family relationships.

We urgently need a reset. Teachers need to be reminded of the important role they play in relation to the transmission of knowledge and, through this, cultural norms and values. They should be rewarded and respected for high levels of subject expertise more than for a general interest in the wellbeing of children.

Similarly, we need greater cultural validation for the institution of the family. Not all families exist in circumstances that parenting experts consider ideal. However, what matters more than either specific circumstances or diligence in following official guidance is that the overwhelming majority of parents love their children and want what is best for them.

Joanna Williams is a spiked columnist and author of How Woke Won. She is a visiting fellow at Mathias Corvinus Collegium in Hungary.

The above is an edited extract from Joanna’s new report, Teachers or Parents: Who is responsible for raising the next generation?, published by Civitas.

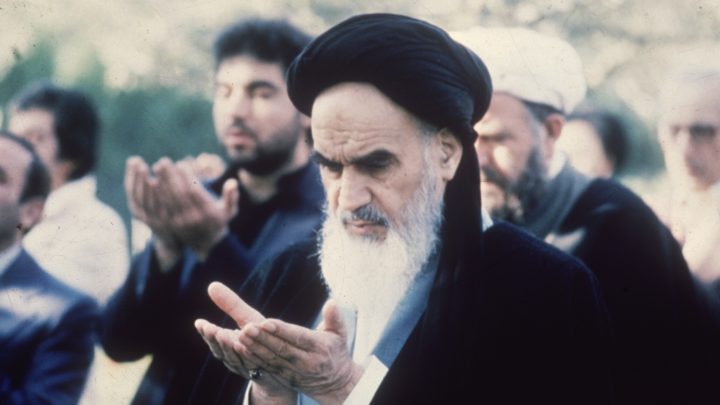

Pictures by: Getty.

(1) SAGE Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Democracy, by James Arthur, Ian Davies and Carole Hahn (eds), SAGE, 2008

(2) ‘Whatever happened to sustainable development?’, by I Selmes, in Teaching Geography, Vol 44, No 3, Autumn 2019, pp108-110

(3) ‘History’, by C Counsell, in What Should Schools Teach?: Disciplines, subjects and the pursuit of truth, by Alka Sehgal Cuthbert, Alex Standish (eds), UCL Press, 2021

(4) ‘History’, by C Counsell, in What Should Schools Teach?: Disciplines, subjects and the pursuit of truth, by Alka Sehgal Cuthbert, Alex Standish (eds), UCL Press, 2021

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.