Long-read

Why the West must fight for its history

The culture war against the past is depriving us of a future.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In my new book, The War Against the Past: Why the West Must Fight For Its History, I argue that unless we retrieve our historical memory, we are doomed to a state of cultural paralysis.

This act of retrieval won’t be easy. Our historical memory is under sustained assault by a significant swathe of our cultural elites. While many involved in this culture war appear to be focussed on controlling the way we speak and think in the here and now, their main mission is to render toxic the legacy of Western civilisation. This ceaseless attack on our history threatens to distort society’s memory of the past and create a state of historical amnesia.

My principal argument is that a key driver of this elite culture war is, as the title of my book suggests, an undeclared war against the past. At times, supporters of the culture war against Western civilisation behave as if its legacy is a menace to the contemporary world. Their frenetic targeting of Western civilisation’s symbols, values and achievements is designed to make people feel ashamed of their cultural origins and who they are. They believe that through gaining control over the representation of the past they can acquire ideological hegemony over the present.

This project goes beyond the rewriting of history. It is about directly intervening in and poisoning society’s memory of the past, and delegitimatising its great achievements. Take the recent decision of the National Gallery in London to present John Constable’s iconic 19th-century painting, The Hay Wain, as a ‘contested landscape’. The curators’ aim here is not to showcase a great work of art but to outline what Constable should have painted. They effectively chide Constable for failing to address the social problems that plagued rural England in the late 18th and early 19th century. ‘Contesting’ this work of art entails questioning its integrity, and encouraging viewers to adopt a cynical attitude towards Constable’s idyllic vision of the rural past.

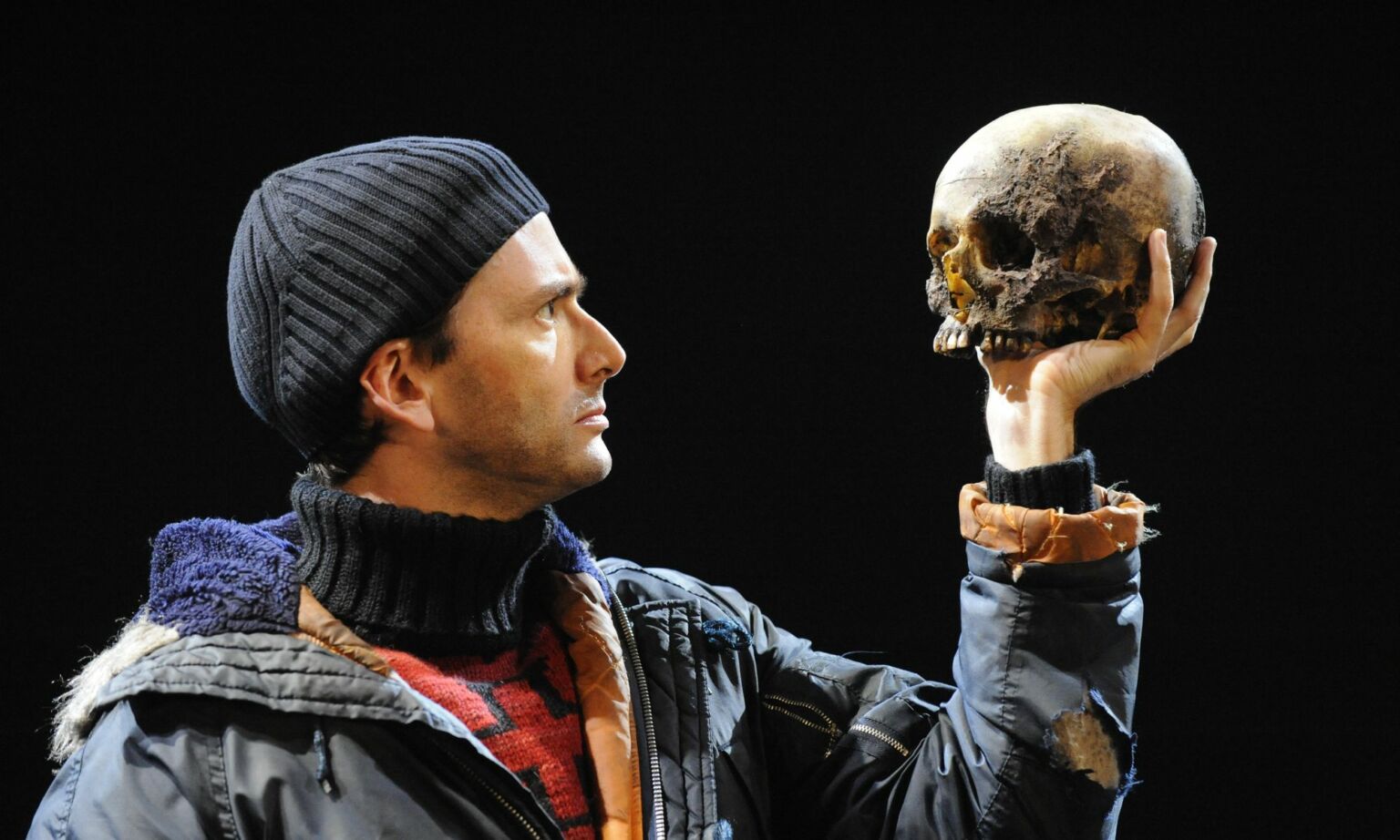

This attempt to contaminate the past and turn great historic figures into our moral inferiors is often animated by a spirit of revenge. Shakespeare is a favourite target. He is frequently attacked today as a proto white supremacist, despite race not existing as a concept in 16th-century England. Like the National Gallery curators accusing Constable of covering up social injustice, countless academics and writers anachronistically claim that Shakespeare’s great plays carry a racist message. One theatre company even changed the language of Titus Andronicus, ahead of a run at London’s Globe Theatre in 2022, so as to bring out its supposedly implicit racist character. Director Jude Christian said that the language of the production needed to resonate more clearly with the outlook of contemporary audiences. ‘Racism in the play is masked by Shakespeare’s language’, said Christian. ‘What we’ve done is show clearly what the words meant in Shakespeare’s time.’

But Christian’s production didn’t really bring out the meaning of Shakespeare’s language. Rather, it put present-day words into Shakespeare’s mouth. It replaced antiquated 16th-century terms, such as ‘Moor’ and ‘raven-coloured’, with contemporary racial terminology like ‘black’. Through this rewriting, 21st-century ideological attitudes towards race are inserted into a play over four centuries old.

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, the Globe even organised anti-racist Shakespeare webinars to discuss race and social themes in Shakespeare’s work. At one American University, Titus Adronicus and other Shakespeare plays were ‘discussed through the lens of critical race theory’.

For today’s culture warriors, what’s important about Shakespeare is not the beauty and audacity of his use of language but his work’s alleged hidden meaning. Those who seek to racialise the Bard’s texts are far more interested in what he did not say than what he did. They arrogantly assume that their versions of these plays, based on what he ‘really meant’, are superior to what Shakespeare actually wrote.

There’s a reason Shakespeare in particular is being presented as an ideologue of ‘whiteness’. It’s because he is recognised as arguably the key figure in the Western canon. By painting him as a proponent of white supremacy, culture warriors are trying to sully the reputation of one of the foundational figures of our entire literary tradition. They want to push him off his pedestal, leave his entire corpus of work compromised and devalue the canon itself.

Culture-war assaults on the likes of Constable and Shakespeare are now the norm. There has rarely been a time when so much energy has been devoted to questioning and criticising historical figures and institutions. Activists appear to be trying to fix contemporary problems by attacking and colonising our shared historical legacy. In doing so, they are erasing the boundary between the present and the past.

The crusade against the past has proven particularly successful at alienating wider society from its own history. Public and private institutions ceaselessly paint history in the darkest colours, and apologise for just about everything that has happened, no matter how long ago. Even the most spectacular achievements of human civilisation, from Greek philosophy to the Enlightenment to the scientific and technological advances of modernity, are now regularly indicted for their supposed association with exploitation and oppression. It is not just a small clique of headline-grabbing historians engaged in these attempts to draw attention to the malevolent, oppressive, exploitative and abusive dimension of the past. In many cultural spheres today, history now possesses the status of the ‘Bad Old Days’.

Those damning history in such terms often call for a break with the past and its legacy. They argue that this is necessary because wider society is not able to acknowledge the wrongs perpetrated by previous generations. They argue that the negative features of the past greatly outweigh the positive ones, and are sceptical of the value of a cultural inheritance that has inspired communities for centuries.

They reserve much of their moral condemnation for the historic achievements of European societies. In these negative histories, inspiring historical experiences and achievements are downplayed or called into question. It is what Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey, during arguments over Australia’s treatment of aboriginal peoples in the 1990s, described as the ‘black armband’ view of history – a history, that is, of mourning past misdeeds.

According to one American proponent of this school of negative history, the United States ought to view its very foundation as a source of shame. It does ‘not yet have the stomach to look over its shoulder and stare directly at the evil on which this great country stands’, she writes. According to this view, writ large in the New York Times’ ‘1619 Project’, the United States’ past possesses few redeeming qualities.

In these negative, accusatory histories, a teleology of evil is at work. They reduce history to a tale of unfolding malevolence – a malevolence that continues to manifest itself in oppressive and exploitative behaviour today. For those who subscribe to this perspective, it is essential to cleanse the present of the influence of the past, to wrest the present free from history. In recent times, this view has evolved from a need to break with history to a desire to exact revenge on it.

This results in a paradox. Those wanting to wrest the present free from the past are simultaneously obsessed with it. This paradox is expressed by advocates of what I call Year Zero ideology. They have twin objectives: to eradicate the past and to denounce the historical memory associated with it. They want to condemn Western civilisation while simultaneously damning and punishing ever more figures and achievements from the past.

Year Zeroists are judging the past according to the norms and values of today, and in doing so they look down on everyone who preceded us. This disdainful attitude towards the world of our ancestors makes no allowances for the different historical circumstances within which they lived. Nor does it appreciate the long and difficult journey on which humanity embarked thousands of years ago. Instead of seeking to understand the different historical experiences through which individuals’ and communities’ attitudes and behaviour developed, Year Zeroists prefer instead to indict them for their superstitious, tradition-bound and oppressive behaviour.

This is to read history backwards. It is to treat past societies in accordance with the experiences and values of the contemporary world. People from the past are contemptuously dismissed as moral inferiors who lack the awareness of their 21st-century critics.

This amounts to a self-flattering presentism. It diminishes society’s sense of historical consciousness and inevitably leads to a failure to grasp different historical moments in their specific contexts. The integrity of the cultural achievements of the past is increasingly treated with indifference. This is why contemporary critics engage with a painting by Constable as if it ought to be addressing rural poverty or a play by Shakespeare as if it is a 21st-century political statement.

What we are witnessing is the unravelling of any sense of historical continuity and the development of a deep historical amnesia. In the late 1970s, American historian Christopher Lasch was one of the first to recognise the coming crisis. ‘We are fast losing the sense of historical continuity’, he wrote in The Culture of Narcissism (1979), ‘the sense of belonging to a succession of generations originating in the past and stretching into the future’.

Since the 1970s, this loss of any sense of historical continuity has mutated into a consciously induced form of historical amnesia. As historian Tony Judt warns:

‘Of all our contemporary illusions, the most dangerous is the one that underpins and accounts for all the others. And that is the idea that we live in a time without precedent: that what is happening to us is new and irreversible and that the past has nothing to teach us.’

The war against the past has further weakened our consciousness of history and fuelled our social amnesia. This poses serious challenges. Presentism limits society’s understanding of historical variability and change, and the role human agency plays in the making of the world.

Contempt for the achievements of our ancestors is profoundly anti-human. By asserting that people in the past have achieved so little worthy of preservation and praise, today’s culture warriors call the moral status of humanity itself into question.

The harm done by the vandalisation of the past lies all about us. Young people are now growing up with a weak sense of connection to what preceded them. They are the human casualties of the war against the past.

This attack on the past also affects Western society’s relationship with the future. We used to view it largely as an opportunity to build on the shoulders of our ancestors, a chance to continue and improve upon the world they had bequeathed to us. That positivity and confidence has evaporated. Today, trapped in a presentist quagmire, the West has turned in on itself. It is full of self-loathing. George Santayana, the Spanish-American philosopher and poet, once said that ‘those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’. A nation that cannot remember its own history deprives itself of a future.

Re-reading Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, I am struck by a passage warning of the loss of historical memory. A colleague in the Records Department of the Ministry of Truth warns the novel’s protagonist, Winston Smith:

‘By 2050 – earlier probably – all real knowledge of Oldspeak [standard English] will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron – they’ll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely changed into something different, but actually changed into something contradictory of what they used to be.’

It is not yet 2050, but a crusade designed to distort the understanding of the past is in full swing. Today’s Ministry of Truth operatives are systematically robbing society, especially young people, of their cultural inheritance. Their objective is to turn the past into an object of shame.

A society that becomes ashamed of its historical legacy invariably loses its way. Its capacity to socialise its children quickly weakens, plunging them into a permanent crisis of identity. It is our responsibility to the young to ensure that they have access to the legacy of the past. It provides the foundation for genuine solidarity across society and across generations. Without it, society becomes de-historicised, lost in a timeless wasteland.

As Shakespeare reminded us through the mouth of the Earl of Warwick: ‘There is a history in all men’s lives.’ Human beings are historical animals and the past lives through us. The possession of a sense of the past is integral to what it means to be human. Without it, we are all lesser beings.

These are perilous times. But the war against the past is not over. There is still much to fight for.

Frank Furedi is the executive director of the think-tank, MCC Brussels.

His new book, The War Against the Past: Why the West Must Fight For Its History, is published by Polity. Order it here.

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.