2023 revealed the tyranny of the ‘sensitivity reader’

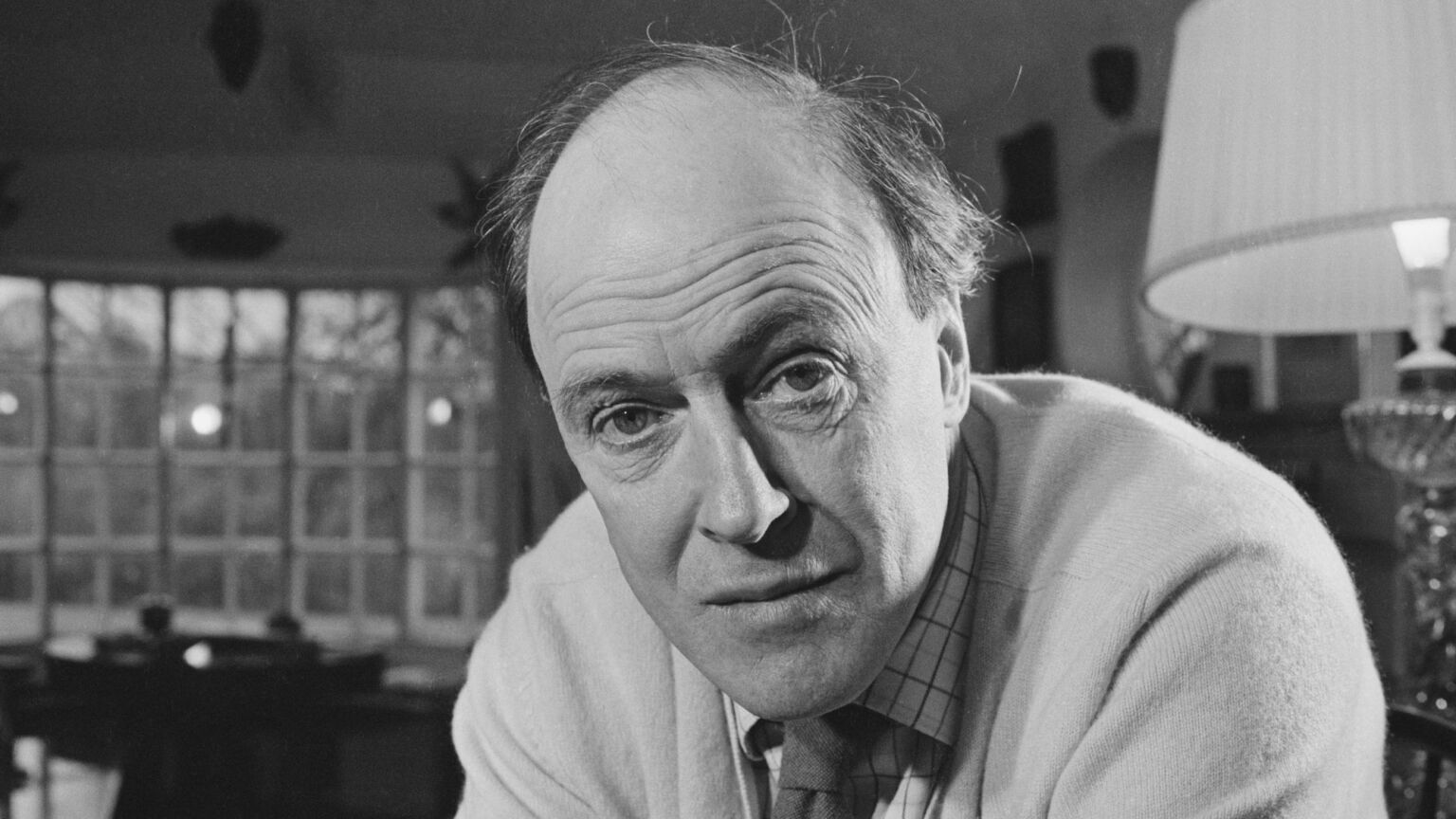

From Roald Dahl to PG Wodehouse, no literary genius is now safe from the censor’s pen.

Perhaps we should be pleased, reassured, that literature is still considered to be of sufficient importance, to have power to persuade, that it is still policed to the same extent today as social media, academia and film. 2023 was the year that pretty much any work of literature became fair game for censorship, re-editing or ‘re-imagining’.

This magazine – and your present correspondent, in fact – noted a number of the skirmishes as they came. First to come under attack, in February, was God. Specifically, God the Father, as he is described in the Bible, the holy book itself. And His critics were, of course, coming from inside His house. The Church of England’s Liturgical Commission proposed using gender-neutral terms to describe the almighty in services. It even suggested dropping ‘Our Father’ from the Lord’s Prayer. The fear was that presenting God as a father might be triggering to those who either had none or perhaps had suffered at the hands of a less-than-infinitely-loving one. This suggestion was very clearly nonsense, and it seems to have smouldered and been parked for now.

The next outrage came in March, with a deliberately provocative BBC ‘re-imagining’ of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, often cited as his masterpiece. Whenever the Beeb adapts a Victorian classic these days it can be expected to grate and this was no exception. It was, of course, ‘dark’, both linguistically (plenty of oaths were rather more explicit than in the original) and visually, in its Christopher Nolan-esque colour palette. And, as you’d expect, the casting was ‘diverse’, not to say wildly inaccurate. But as many people pointed out, at least the book remains available to anyone who wants to access those more nuanced qualities that earned Dickens such affection in the first place.

The same cannot quite be said of PG Wodehouse, whose Jeeves and Wooster novels were tweaked, tinkered with, smartened up, toned down and made fit for modern consumption back in April. Most notably, surgical incisions were made into both Thank You, Jeeves and Right Ho, Jeeves, which many regard as containing the most perfect comic prose in the English language – all to excise the use of the n-word.

For those of you who missed the story, and are surprised to learn that such a rough racial slur would ever appear in Wodehouse’s immaculate light comedy, it should be said that both Bertie Wooster and his chum, Chuffy, use the word cheerfully to refer to minstrels, apparently oblivious of its oncoming capacity to offend. It is not intended to denigrate anyone, at least not to the extent that it would be today – nor to demonstrate the author’s grasp of authentic street slang.

Does it matter? I doubt the n-word will be missed. The removal was conducted with the approval of Wodehouse’s estate, and I expect the stitches have been removed by now and the scar barely visible. Still, I couldn’t – and still can’t – help feeling uneasy about revisionism of this kind, and especially with tales as innocent as these.

Worse, in my view, was the meddling of ‘sensitivity readers’ in the genius of Roald Dahl back in February. His publisher, Puffin, made hundreds of changes to his classics. The Oompa-Loompas from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory are no longer ‘tiny’ or ‘titchy’, just ‘small’, and are gender-neutral ‘people’ instead of ‘men’, for some reason. Augustus Gloop is no longer described as ‘fat’, nor is any plus-sized character in Dahl’s updated oeuvre. In some cases, whole sentences have been excised and new lines added to preempt any potential for causing offence.

Unlike Wodehouse, who could pass across a field of wildflowers without denting a single daisy, Dahl can be deliberately trampling, viciously so. Cruelty is part of the recipe with Dahl. Many characters in his books, both adult and children, are exposed to his withering contempt, whether for character flaws which they might be expected to correct, or for their physical deformities, which they might not.

So, when Dahl calls a child fat or draws attention to a witch’s large nose, you cannot simply pluck these out and replace them with more ‘inclusive’ insults without neutering the entire project. They are porcupine quills, intended to wound. Without them, what you have is an overgrown Guinea pig.

This year, beloved characters were ‘updated’ for the times, too. The once-swaggering James Bond has now been tamed and domesticated, at least in the new Bond books. Charlie Higson’s novel, On His Majesty’s Secret Service, was commissioned for the coronation of King Charles. Unlike Ian Fleming’s Bond, who thought nothing of uttering racial slurs and aggressively seducing women, the 21st-century Bond can mostly be heard complaining about cringeworthy UKIP types and golf-club bores.

The key takeaway from all this is probably the same as it has been for some years: if there is an author you value or think you might like to investigate in the future, then it is probably worth getting hold of second-hand copies, or at least avoiding Kindle. Now that the literary vandals are inside the gates, no book is safe from their meddling.

Simon Evans is a spiked columnist and stand-up comedian.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.