The civil service needs to grow up

Accusations of ‘bullying’ belong in the playground.

The ousting of Dominic Raab over ‘bullying’ should worry anyone who wants to live in a robust, grown-up society. The former UK deputy prime minister was effectively forced to resign last week, following the publication of a report into his behaviour. Civil servants of various Whitehall departments had lined up to accuse him of bullying them. The weight that has been given to their allegations should trouble us all.

Accusations of bullying are far more prevalent now than they used to be. The charge is, by definition, a subjective one. The bullying complaints against Raab were upheld on the grounds that he acted in a ‘way which was intimidating… and persistently aggressive in the context of a workplace meeting’. Adam Tolley KC, the lawyer in charge of investigating the complaints, concluded that Raab’s ‘conduct was bound to be experienced as undermining or humiliating by the affected individual and it was so experienced’. He inferred that Raab ‘must have been aware of this effect; at the very least, he ought reasonably to have been so aware’.

Reading between the lines, it appears that Raab was an assertive, demanding and possibly insensitive person to work with. Clearly, he took his work very seriously and was concerned with getting the job done. He paid little attention to the egos of his civil servants. Nowadays, such single-mindedness in the workplace is treated as evidence of bullying.

There was a time when bullying was perceived as an unpleasant but unavoidable part of growing up. The word used to refer to the actions of children and the aggressive or anti-social behaviour exhibited by some kids towards their peers. It wasn’t viewed as a problem that might afflict adults. That was until the 1990s, when one survey after another reported that bullying had reached epidemic proportions in the workplace. Teachers complained that they were being bullied by parents. Campaigners argued that workplace bullying not only caused distress, but also serious mental-health problems.

In 2012, in Australia, a parliamentary commission estimated the total cost of ‘workplace bullying’ to be between $6 billion and $36 billion annually. At the time, Australia’s then workplace-relations minister, Bill Shorten, described workplace bullying as a ‘secret scourge’ that was ‘far too common’.

Workplace bullying now covers a multitude of sins. Virtually any negative or uncivil encounter can be defined as bullying. The term now encompasses everything from sarcastic put-downs to vandalism, from crude gestures to unwanted eye contact. This inflation of the meaning of bullying suggests that grown-ups are now finding it difficult to deal with any emotional challenge. Gossip and snide remarks are now discussed as if they are unbearable threats to the adult psyche. This is incredibly infantilising.

Nowadays, even miscommunication can be represented as bullying. Widely accepted definitions of bullying insist that the victim’s feelings, rather than the intention of the perpetrator, are what counts. For instance, the Australian Medical Association defines bullying in the following terms: ‘Sometimes bullying is deliberate and intended to make a person upset. But it can sometimes still be bullying if someone repeatedly acts in ways to make a person upset or frightened, even if it is not deliberate.’

As Dominic Raab has discovered to his cost, your intentions now provide no defence against the charge of bullying. The harm caused by the unwitting bully is supposedly no less serious than if he or she had intended to cause someone pain. This shift in the meaning of bullying has been propelled by the modern notion that even adults are ‘fragile’ and need to be protected from nebulous forms of ‘harm’.

The current bullying narrative erases the distinction between adult and child. It treats all stressful and negative experiences as potentially traumatic and unbearable. And as Raab’s case has shown, when several colleagues join together to denounce someone as a bully, their claims are readily accepted. When a few people claim they feel hurt and humiliated, this can now be taken as proof that a workplace is dominated by a ‘culture of bullying’. Any leader who is assertive, or has an uncompromising work ethic, is likely to fall foul of this ethos.

The fact that so many mature adults are behaving like put-upon children is a serious problem – especially for an institution as important as the civil service. These civil servants need to grow up and start taking themselves seriously.

Frank Furedi is the executive director of the think-tank, MCC-Brussels.

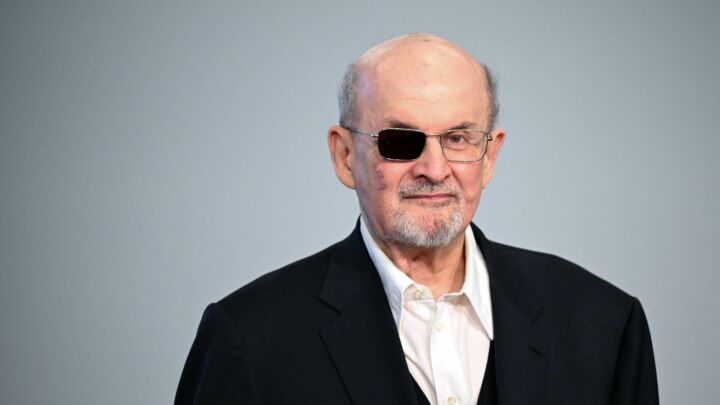

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.