An eye for a hurt feeling

The attack on Salman Rushdie exposed just how medieval cancel culture can be.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

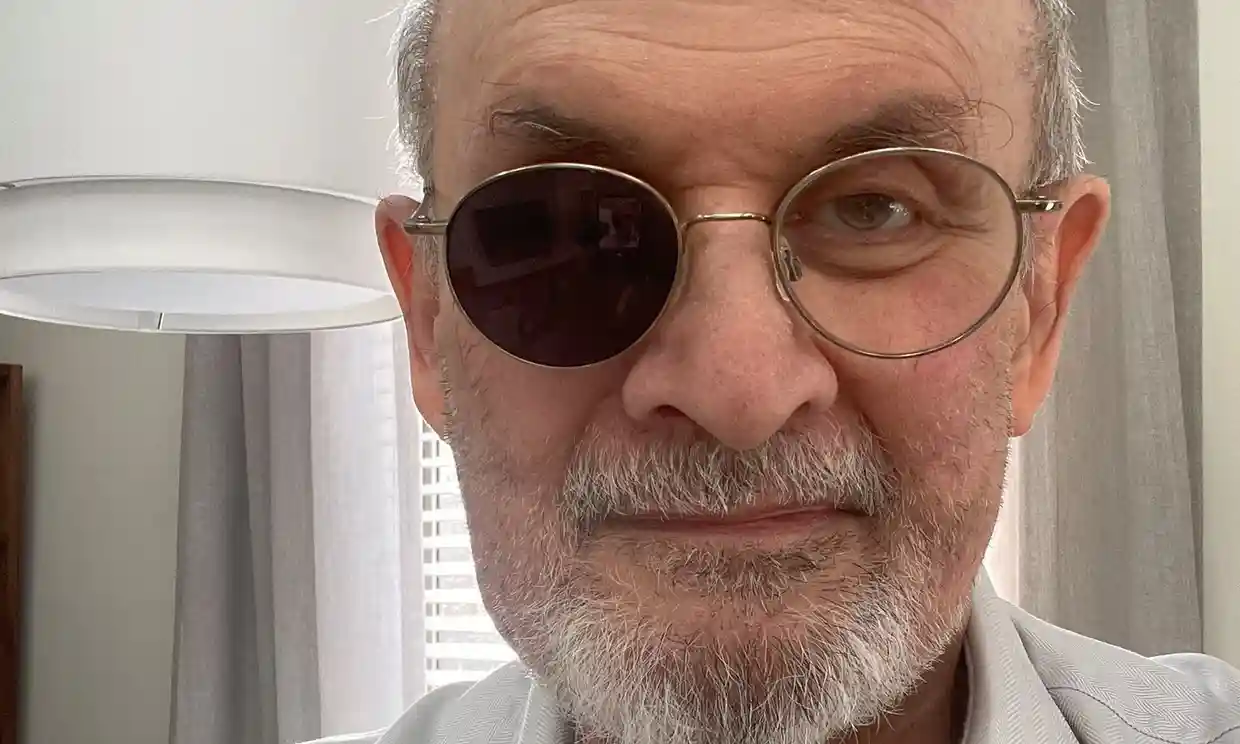

We look back with horror at the idea of an eye for an eye. At that Old Testament belief that vengeance was the best form of justice. And yet in our unforgiving era of cancellation, we face something even worse. Now it’s an eye for a hurt feeling. An eye for a bruised ego. Behold the new photo of Salman Rushdie, the first to be published since he was brutally attacked in New York state in August last year. He’s wearing glasses with the right-hand lens blacked out. That’s because he’s blind in his right eye. A man felt offended by a novel Rushdie wrote 35 years ago, and he took one of Rushdie’s eyes as compensation.

Everyone should look at Rushdie’s face following the medieval assault on him last year. Those who use the word ‘Islamophobia’, who believe criticism of Islam is a moral ill society should not tolerate, should be forced to look, so that they might see the wages of their ideology. The photo appears in the New Yorker alongside an interview with Rushdie by David Remnick. Rushdie was stabbed around a dozen times. He has scars on his face. His mouth droops when he speaks. He finds it difficult to type because the severing of the ulnar nerve in his left hand took away the feeling in his fingertips. Reading is difficult too, following the butchering of his sight. He now ‘reads with an iPad so that he can adjust the light and the size of the type’. In the Inquisition a tongue-tearer was used to cut out the tongues of those who uttered heresies – in the New Inquisition a writer has his ability to write violently stymied for his crime of offending Islam.

One of the most disturbing things about the attack on Rushdie was the silence that followed it. Sure, there was an explosion of media coverage in the hours and days after Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old American citizen of Lebanese origin, allegedly stabbed Rushdie on stage at the Chautauqua Institution over his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses. But it fizzled out with unseemly, spineless haste. There were a handful of small pro-Rushdie public readings, but a ‘Je Suis Salman’ movement was notable by its absence. The attempted extrajudicial execution of one of the great novelists of the modern era for writing a novel that the ayatollahs disapproved of did not bother the Western conscience for very long.

One was forced to wonder if silence is still violence. ‘Silence is violence’ is the great rallying cry of the woke, beloved of BLM protesters in particular. If you stay schtum in the face of injustice, they say, then you’re party to that injustice. So was the deafening hush among ‘progressives’ following the suspected Islamist strike against Rushdie a kind of complicity, too? Was that silence violence? It was certainly cowardice. The low instinct for self-preservation, for doing everything in one’s power to avoid attracting the attention of Islamist hotheads, became the organising principle of the West’s cultural and media elites. Literary solidarity be damned – we have our necks to protect.

Two days after the attack, a writer for the Atlantic said the lack of righteous outrage over Rushdie’s stabbing pointed to a ‘faltering of the culture’. We no longer seem to believe, he said, ‘that the liberty of individuals is worth fighting and dying for’. This elite sheepishness over an alleged act of Inquisitorial terror echoed the shameful behaviour of sections of the literary establishment when Iran first issued the fatwa in 1989. As Remnick reminds us, many in the great and good failed to back Rushdie back then. John le Carré suggested he withdraw his novel ‘until a calmer time has come’. Roald Dahl denounced him as a ‘dangerous opportunist’. Cat Stevens said he should have known that, according to the Koran, ‘if someone defames the prophet, then he must die’. Jimmy Carter, Germaine Greer, Auberon Waugh, the Archbishop of Canterbury and others all expressed their disapproval of Rushdie and his boat-rocking book.

But in some ways, the silence after the stabbing was even worse. It wasn’t just a case of looking down at one’s feet in the hope that the violent Islamist cancellers will pass you by, which would have been bad enough. It was also brute confirmation that some in the new elites actually share the Islamist belief that it is wrong to mock Islam. Sure, they would never assault Rushdie or attack the offices of Charlie Hebdo. But they agree with those people’s violent tormentors that blasphemy against Islam – or ‘Islamophobia’, as it’s fashionable to call it – is a socially destabilising thing that causes ‘suffering’. Remember when big-name writers challenged PEN America’s presentation of Charlie Hebdo with an award for courage? The massacre was sad, they said, but let’s not forget that Charlie Hebdo’s potshots at Islam are designed to cause ‘humiliation and suffering’. This speaking of the ‘suffering’ of hurt feelings mere months after the infliction of real violent suffering on Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists and writers was a testament to the moral disarray of the modern elites.

This is the dark truth of the Rushdie affair: it represents a merging of old-style religious intolerance with the new secular creed of cancellation. Rushdie for the past 30-odd years has been caught in a kind of pincer movement, with pious religious censors on one side and politically correct controllers of public discourse on the other. The attack on him in August was not as alien to our civilisation as we would like to believe. It was really a more violent, more medieval manifestation of an idea that is tragically commonplace now – that words wound, feeling offended is terrible, and steps must sometimes be taken to blacklist or silence those who hurt your feelings. Hadi Matar might yet prove to be simply a more menacing enforcer of the cult of cancellation that has Western society in its baleful grip.

The liberal capitulation to the violence of the easily offended must end. Let us instead remember Rushdie’s outline in Joseph Anton of things it is really worth ‘fighting for’ – ‘Freedom of speech, freedom of the imagination, freedom from fear… Also scepticism, irreverence, doubt, satire, comedy and unholy glee.’ We must never ‘flinch from the defence of these things’, he said. Now those are words to live by.

Brendan O’Neill is spiked’s chief political writer and host of the spiked podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show. Subscribe to the podcast here. And find Brendan on Instagram: @burntoakboy

Picture by: Twitter / SalmanRushdie .

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.