A brief history of the end of the world

Religious visions of the Final Judgement live on in modern fears about the climate.

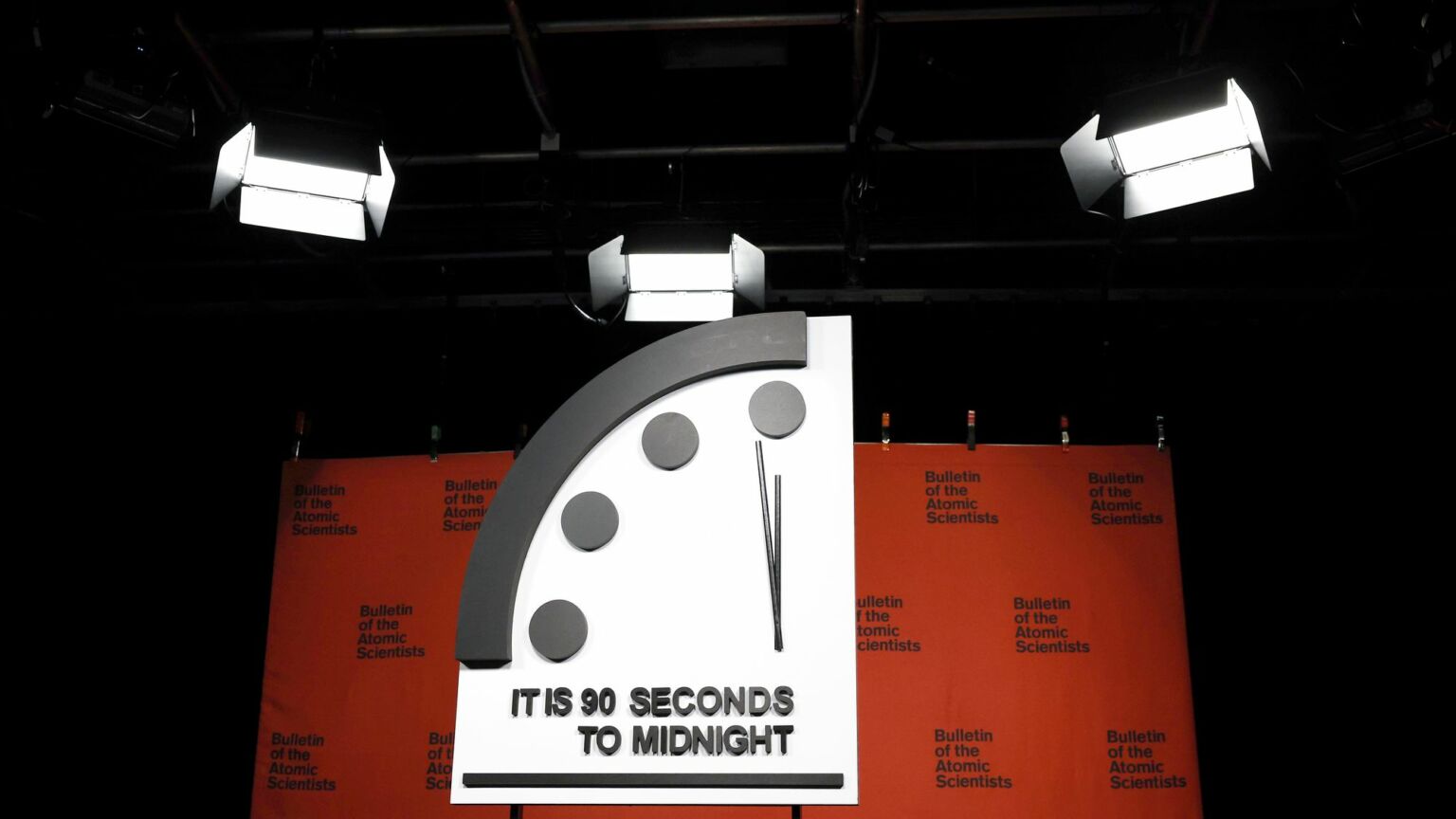

Fearing a nuclear war over the conflict in Ukraine, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has moved its ‘Doomsday Clock’ forward another 10 seconds. Apparently, we are now at 90 seconds to midnight, meaning that humanity is closer to oblivion than ever before.

The Doomsday Clock, as even its custodians admit, ‘is not a forecasting tool’. Rather, it is a symbolic visualisation of the potential threats posed to mankind. The scientists of the Bulletin meet twice a year to assess this threat level. This month, they were looking at the conflict in Ukraine and the number of nuclear warheads in the world. They also took into account the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the acidity of the oceans and rising sea levels. Other supposed threats the Doomsday Clock now incorporates are infectious diseases and, bizarrely, online disinformation.

It is true, of course, that the war in Ukraine is a profound threat to the people who live there. It also has a very real potential to set off wider conflicts across Europe and the world. Russia is, after all, a nuclear power. Still, a singular fixation on the potential for a nuclear extinction-level event is an unhelpful distraction from the conflict on the ground.

Ever since it was established at the outset of the Cold War, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has championed détente and has called for nuclear disarmament. This concern with nuclear armageddon was understandable during the Cold War – the development of rival nuclear arsenals certainly put vast swathes of the world in jeopardy.

On the other hand, during the Cold War, while radicals fixated on the horizon of nuclear destruction, the widespread militarisation of the rest of the world was often overlooked. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists joined peaceniks in singing ‘Kumbaya’ outside cruise-missile stations, while the great powers carried on waging dirty wars in the developing world.

The End Times holds a powerful grip on our collective imagination. The trouble is, when that grip becomes too powerful, we lose sight of more tangible problems in the here and now.

The fancy word for doomsaying is ‘eschatological’. That is to say, fixed on the end. It comes from the Greek word eschaton, which refers to the religious idea of the Day of Judgement, the realisation of God’s plan for the world. The Greeks also gave us the word ‘apocalypse’ – when a deity reveals the cosmic mysteries.

Apocalyptic or eschatological prophecies tend to come to the fore in times of misery or disorder. They are an expression of despair. Towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Joanna Southcott electrified tens of thousands of Britons with her revelation that she was to give birth to the Messiah on 19 October 1814, despite her being 64 at the time. When the date passed without event, the Southcottian movement broke up, although a few followers persisted.

Some apocalyptic prophecies have proved more enduring. In the 1870s in Pennsylvania, Charles Taze Russell’s ‘Watch Tower’ congregations predicted that God’s Kingdom on Earth would be inaugurated in 1914, only for the Great War to break out instead. After another failed prophecy for 1918, and again for 1925, the group re-established itself as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who today still look forward to the Second Coming.

Unsurprisingly, apocalyptic attitudes were common during the First World War, when people were being killed in their millions. In the interwar years, science-fiction stories began to imagine yet more routes to the End Times, like HG Wells’ The Shape of Things to Come. When it came to the political scene of the time, death cults were common on the far right. German philosopher and Nazi Party supporter Martin Heidegger wrote positively about ‘being-towards-death’ (Sein-zum-Tode), arguing that looking towards death is an integral part of the human experience.

After the Second World War, and with the advent of the Cold War, organised religion declined. But the apocalyptic visions continued under more secular guises. The squeezed middle classes, caught in between the worldly demands of big business on the one hand and militant workers on the other, were often prey to the fantasy that the world was coming to a literal end. The middle-class imagination was tortured not only by an impending nuclear winter, but also by the prospect of environmental disasters – particularly the alleged threats posed by overpopulation and pesticides. (Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, predicted a future of barren farmland and an epidemic of cancers and birth defects.) Meanwhile, the influential Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report in 1972 predicted that economic collapse due to resource depletion would happen by around 1990.

Over the past 35 years, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has been gathering scientific evidence of global warming. This is routinely given an apocalyptic interpretation by middle-class green activists seeking to dramatise their demands. In the late 2000s, greens became fixated with the idea that carbon emissions in the atmosphere would soon take the Earth to an irreversible tipping point. Eco-activist Andrew Simms launched his own version of the Doomsday Clock in the Guardian in the summer of 2008, saying that we had just 100 months to save the planet – that is, until the end of 2016. Of course, 2016 came and went, and the world did not end.

Objectively speaking, human life on Earth will eventually come to an end. In around five billion years from now, the Sun will become a red giant, expanding and engulfing Earth in unsurvivable heat. But that need not worry you or me too much. The greater danger today is that, overcome by an existential angst too overwhelming to deal with, people will become incapable of coping with day-to-day problems that could actually be addressed.

We are starting to see this play out in children and young people. Child psychologists Mala Rao and Richard Powell have warned that significant numbers of young people are profoundly distressed by what they’ve heard about climate change. Many believe that humanity has no future. This is despite the fact that deaths from climate-related disasters have been on a downward trend over recent decades. When a problem like climate change is presented as an apocalyptic threat, it is inevitable that a lot of people will feel paralysed rather than activated.

Spreading doom and gloom about the end of the world solves nothing and helps no one.

James Heartfield’s latest book is Britain’s Empires: A History, 1600-2020, published by Anthem Press.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.