How we gave up on education

School closures and rampant grade inflation have had disastrous consequences for young people.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

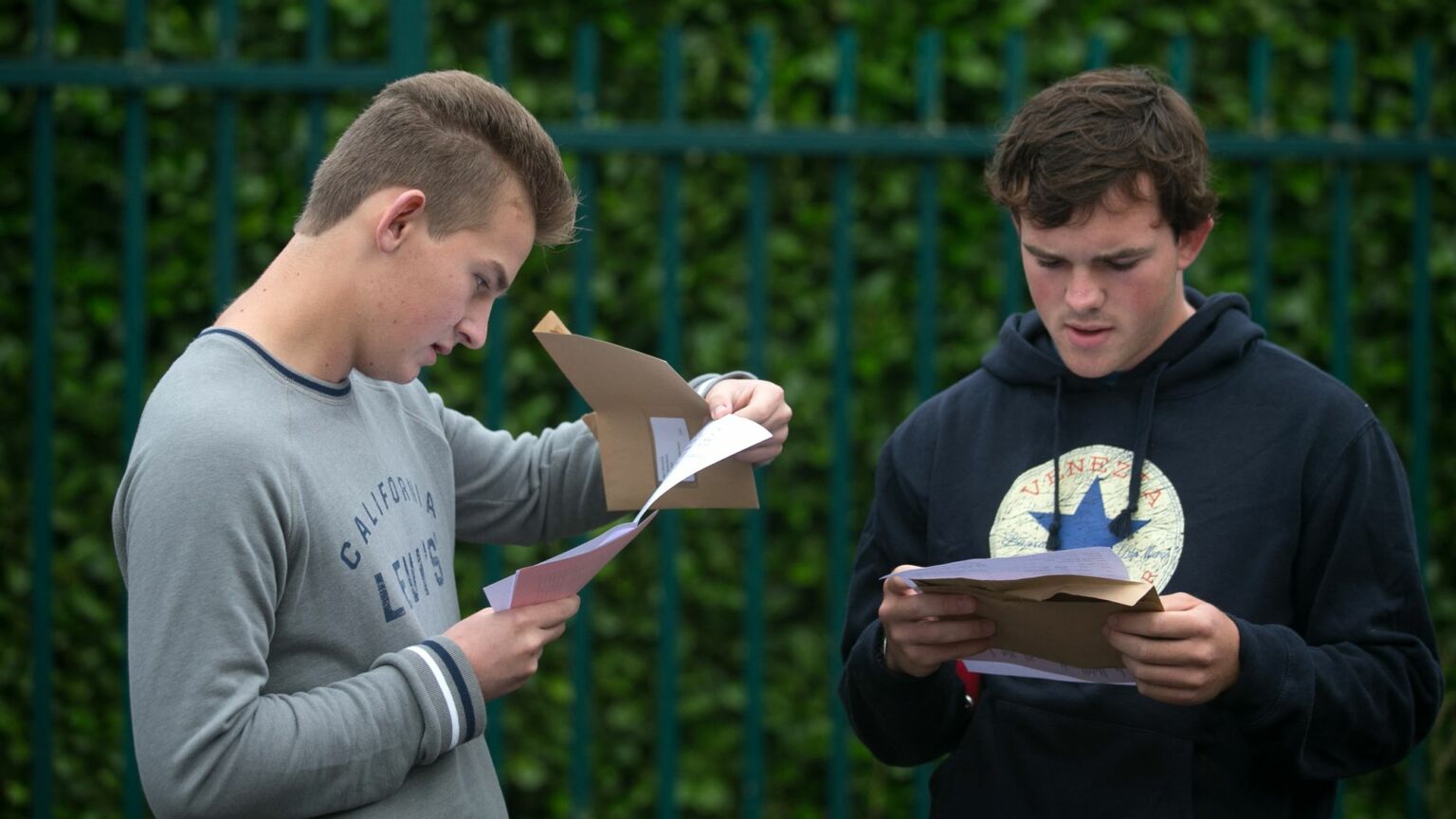

It’s hard not to feel sorry for those young people due to get their A-level results this week. Not only did lockdown school closures disrupt their education, but they are now predicted to end up with lower grades and fewer university places than past cohorts.

A-level results look certain to be lower this year than in either of the past two years, when exams did not take place. What is striking is that this is not in any way a reflection on the effort or ability of this cohort of students. Instead, the Department for Education (DfE) wants results to return to the levels they were at before the pandemic. This year is supposed to represent a mid-point, with results pegged half way between last year’s peak and 2019’s much lower threshold. Manipulating grade boundaries in this way suggests that, at the national level, exam results are more a political football than an accurate record of academic achievement.

That the DfE needs to do this at all is a tacit admission that the teacher-assessed grades awarded during the two years of Covid disruption were hugely inflated. This time last year, we were expected to buy into the fantasy that less education – less teaching, less time in the classroom, less time working with classmates – could magically produce better results. According to this logic, shutting schools completely would ensure all children an A grade in every subject.

This is, of course, nonsensical. But the ‘higher grades for less time in the classroom’ trick served an important purpose. It allowed the disastrous impact of school closures to be swept under the carpet. The flurry of certificates meant fewer awkward questions about what children had actually missed while schools remained closed for so long. Many pupils and teachers no doubt worked extremely hard to make up for lost opportunities. But for the education establishment to try to pretend that overall results were not just normal, but actually better than in previous years, was to engage in an unconscionable cover-up. It was a cowardly attempt to evade accountability.

One worrying trend that would have been far more apparent without rampant grade inflation is the growing social-class divide in educational attainment. During lockdown, it was clearly documented that children from well-to-do homes could just about keep up with schoolwork, thanks to them having laptops, quiet rooms to work in and parental input, while children from homes without these advantages struggled. Since schools fully reopened in March 2021, shockingly little has been done to ameliorate this inequality. This year’s Scottish exam results, out earlier this month, confirm that the poorest children north of the border have indeed fallen further behind their more affluent peers.

Nevertheless, the education establishment still refuses to acknowledge that high quality face-to-face teaching is both vital for all children and crucial to the life chances of the poorest.

This growing class divide is also being disguised by changes to university admissions. For the first time this year, students from affluent backgrounds were less likely than other groups to get a university offer. This is because of the widespread use of ‘contextual offers’, which set applicants’ exam results against factors such as their address, the school they attended and family income. Working-class pupils are, of course, fully deserving of university places. But they are also more than capable of achieving them through a combination of good teaching and their own efforts. Positive discrimination tells underperforming schools that they do not need to up their game. And it tells students that intellectual merit, academic excellence and effort are no longer crucial to success.

The same grade inflation is at work in universities, too. The number of first-class degrees awarded to undergraduates has risen from 14 to 36 per cent since 2010. This trajectory continued unabated during the two years when universities stopped face-to-face lectures and seminars.

It’s no wonder, then, that the difference between a first-class degree and a lower grade doesn’t seem to count for much anymore. For instance, it was announced this week that the multinational corporation PwC will no longer expect applicants to have a good degree in order to secure a post. PwC is keen to present this move as a challenge to class privilege. But working hard at school and university has been a well-trodden route to social mobility for generations of aspirational youngsters. The fashion for firsts-for-all and for companies to say ‘we don’t care about your degree result’ tells young people not to bother making the effort.

Perhaps most disturbingly of all, this great educational swindle prevents lessons being learned from the recent past. Rather than school closures being recognised as a disaster that must never be repeated, there is already talk of schools resorting to a three-day week this winter in response to rising energy and staffing costs.

When education itself is no longer considered important, keeping schools open becomes such a low priority. That we are tinkering with grades and entry requirements, instead of actually reckoning with the damage done to education in recent years, makes it abundantly clear how little our society values academic attainment and the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. We seem to have just given up on education.

Joanna Williams is a spiked columnist and author of How Woke Won, which you can order here.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.