Long-read

Brexit is not to blame for our economic woes

The UK economy is in a dismal state – but not because we left the EU.

Britain’s departure from the European Union (EU) was bound to have economic effects. The Single Market is the world’s most obtrusive protectionist bloc, and so British traders now have to tackle onerous border controls, paperwork and checks. Exiting the EU also meant an end to the ‘free movement’ of EU citizens into Britain. Voters in 2016 and 2019 were aware of these repercussions when they backed Brexit. As exit polls showed in 2016, most viewed these as secondary concerns. They were primarily motivated by ‘taking back control’ in order to restore national sovereignty.

But Remainers are not interested in having an argument about democracy and popular sovereignty. Instead, they continue to claim that Brexit is wrong because of its supposedly catastrophic economic consequences. And so they now blame almost every facet of Britain’s indisputable economic malaise, from high inflation to labour shortages, on Brexit.

This is politically motivated guff. Blaming Brexit for Britain’s slump sidelines the genuine sources of our economic decay. And it gets in the way of public discussion about how we as a nation might build a durable and prosperous future.

Ironically, this determination to blame Brexit for everything is letting the Tory government off the hook. Politicians used to blame the EU for their own inaction on economic policy. Now our establishment blames Brexit for Britain’s continuing economic woes, alongside Covid and the war in Ukraine. This ignores the failure of successive governments to pursue a programme for productivity growth.

Blaming Brexit

Commentators and politicians have been voicing their hatred of Brexit with ever greater gusto recently. A combination of Boris Johnson’s spectacular fall, the sixth anniversary of the referendum vote, and the widespread financial hardships being endured by many households have emboldened elite Remainers.

Tory grandee Michael Heseltine has openly said that he sees Johnson’s fall as an opportunity to reverse Brexit. Like other sore losers from 2016, he repeats the mantra that ‘Brexit has had dire consequences for the economy’. Meanwhile, a Financial Times ‘big read’, unironically entitled ‘The deafening silence over Brexit’s economic fallout’, recently summarised the current economic case against Brexit, declaring that ‘the damage is real and it is not over yet’. It went on to reference Britain’s ‘lagging’ post-pandemic trade recovery, its ‘trailing’ business investment record and ‘lost’ productivity. And it implied that Brexit was responsible for the recent OECD forecast that next year the ‘UK will have the lowest growth in the G20, apart from sanctioned Russia’.

Certainly, there are plenty of legitimate business complaints about the post-Brexit arrangements. There are now more obstacles both in recruiting EU workers after the end of ‘free movement’ and in trading with businesses inside the highly protectionist Single Market.

Yet, in our highly regulated, rules-constrained times, businesses and other organisations have long been grappling with operational barriers like this. So is it reasonable to single out the extra post-Brexit regulations as the cause of so much extra damage? And, more importantly, is there really ‘mounting evidence’ of Brexit being an economic ‘disaster’, as Remainers claim?

Much of today’s anti-Brexit economic commentary is woefully simplistic and misleading. It starts with Britain’s truly abysmal economic condition, points out areas where Britain is doing worse than some of its continental neighbours and then concludes that, since these other countries did not leave the EU, Britain’s relative underperformance must be due to Brexit. Logicians might call this the ‘questionable cause’ logical fallacy.

There is little doubt that the British economy is in a worse state than most other advanced industrial economies. This calls for a nationwide debate over the causes and potential fixes for this productivity slump. But to say that it’s all Brexit’s fault is a specious thesis that has little to do with economics. This argument needs to be opposed. Primarily, because it is thoroughly anti-democratic. It is part of an attempt to reverse the result of the 2016 referendum. But the economic arguments should also be criticised on their own terms, because they act to obscure what we really should be discussing about Britain’s economic depression.

The truth about inflation

This ‘Britain is doing worse, so it must be Brexit’ approach is not just logically suspect, it also lacks empirical evidence to back it up. Take inflation, widely seen as the big economic problem of the moment. It is often pointed out by Brexit’s critics that Britain has faced similar price shocks as other Western European countries, from the pandemic lockdowns to the war in Ukraine, yet it has reached higher inflation levels. Remainers say that this divergence must be down to Brexit.

For example, economists at the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) assert that ‘Brexit has amplified the inflationary impact of a simultaneous common shock… Any alternative explanation to Brexit would have to offer another Britain-specific reason for the size and timing of the marked divergence in core inflation rates’. This is a spurious argument.

In June 2022, the ‘core’ inflation rate (excluding energy and food) in the UK was 5.8 per cent and 4.6 per cent in the EU. Does that really constitute a ‘marked divergence’, as PIIE economists suggest? It is worth noting that a comparison between the UK and EU headline consumer-price inflation rates in the same month was even narrower: 9.4 per cent versus 8.6 per cent. So the divergence is really not so marked.

In fact, the UK’s core inflation rate is remarkably similar to the US’s core inflation rate of 5.9 per cent. Everyone recognises that there are specific drivers behind the US’s particular rate of inflation (including a Covid-19 fiscal splurge under presidents Trump and Biden). Likewise, we need to recognise that there are specific drivers behind the inflation rates of France, Germany and, yes, Britain that have little to do with Brexit and the EU.

It is likely that these slightly differing national inflation rates have something to do with each nation’s particular economic structures, the relative state of their economic fundamentals and the specific policy measures taken to keep a lid on domestic prices. James Smith, a developed-markets economist at ING Group, has pointed out one germane factor: ‘The most obvious reason why UK inflation is likely to take a little longer to come down than, say, the eurozone average is that the energy price cap has created a longer lag between higher gas prices and the pass through to consumer prices.’ In other words, the UK’s higher inflation rate is likely a policy driven variation, not a product of Brexit.

As it stands, the more likely reason that Britain is doing worse economically than other European nations is simply because it has a weaker economy, regardless of Brexit. This could be due to the poor underlying state of the fundamentals in Britain, or to the impact of domestic economic policymaking, or both. Indeed, Remainers’ years-long attempts to try to stop the implementation of Brexit, in parliament and the courts, could themselves have had some disruptive economic effects.

Either way, the correlation between Brexit and Britain’s relative economic underperformance is no proof of causation. On the contrary, understanding Britain’s poor economic performance looks like an instance of ‘Occam’s razor’, where the simpler explanation is the best one. In particular, if Britain is being hit worst by recent shocks it is probably because it lacks the material resources and competent political leadership to cope with these shocks. These problems cannot be attributed either to the Brexit vote, or to the end of the Brexit transition period earlier this year.

Spot the Brexit impact

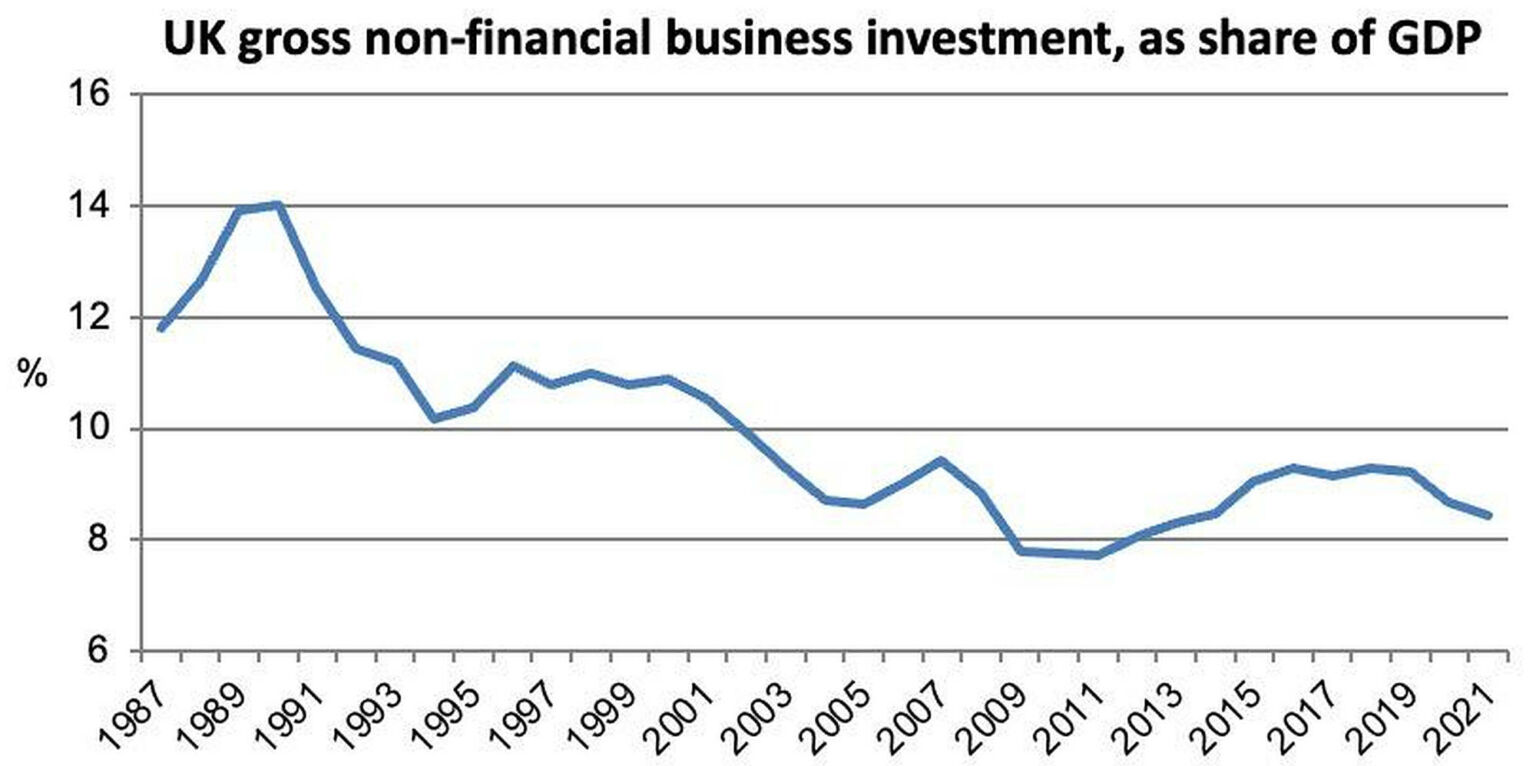

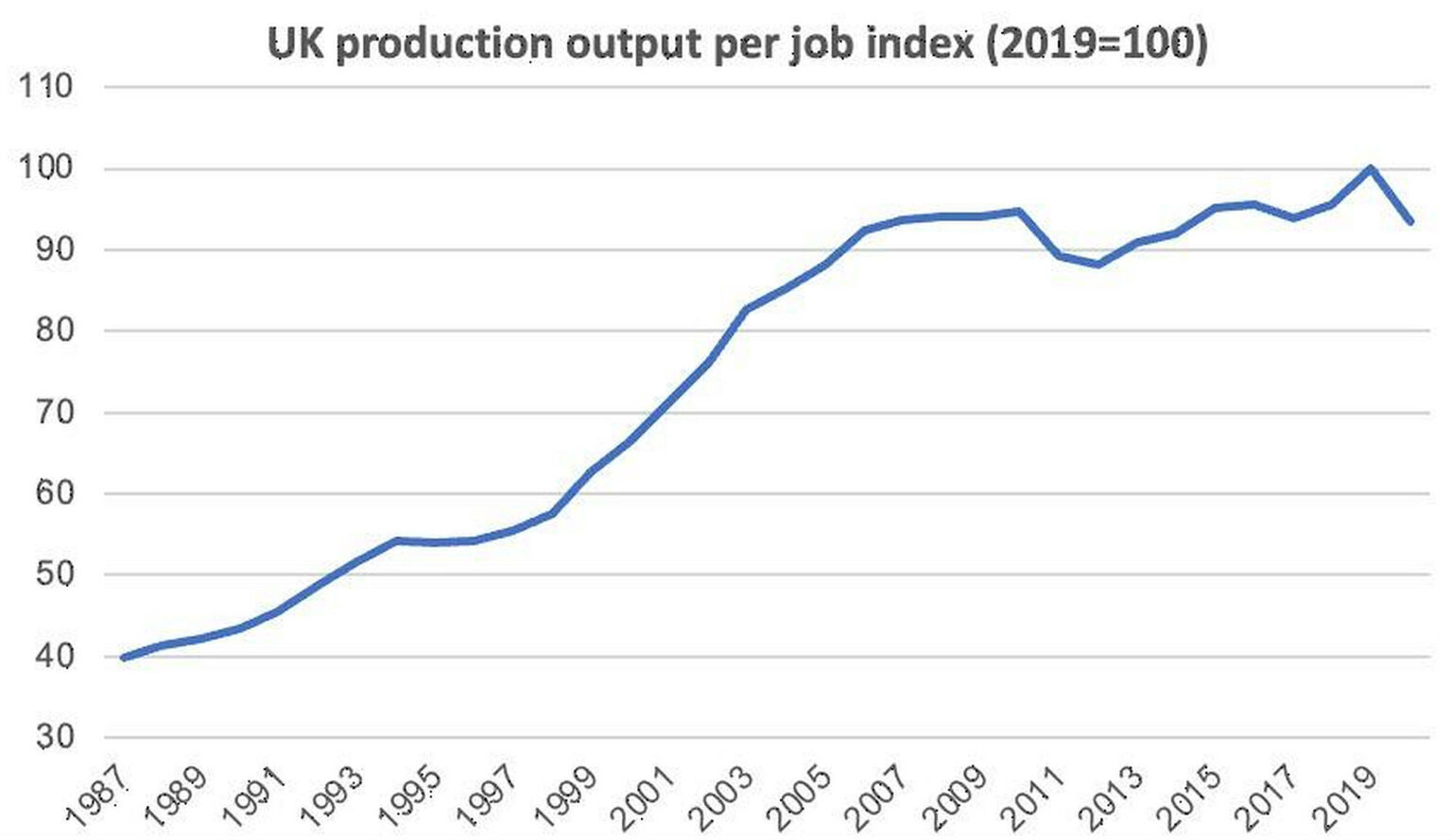

A quick look at the trends in business investment and productivity growth before and since 2016 shows how limited Brexit’s impact has been (see charts one and two below). The trends show that any potential post-Brexit fluctuations – and there always are fluctuations – are a sideshow to the bigger picture of long-term decline in both investment and productivity growth in the UK.

This economic decay existed long before the referendum and does not show much if any additional Brexit influence.

One could legitimately say that it is too early to see much in the data, as the UK’s actual departure from the EU only happened 18 months ago. In addition, over that time, Covid lockdowns and the war in Ukraine will have disrupted and tainted economic data. What seems clear though is that the data so far do not amount to the ‘evidence’ claimed by some unyielding Remainers.

Those ‘missing’ EU workers

What about foreign employment and foreign trade? Adam Posen, the president of the PIIE and a former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, has pointed to the ‘effective exclusion of European migrant workers’ as one way in which Brexit might have fuelled higher inflation.

This is a familiar trope by Remainers about post-Brexit Britain. They frequently declare that Brexit is driving a shortfall in foreign people working in Britain. This is said to have a depressing effect on economic output and a tightening effect on labour markets, which adds to the inflationary pressures.

To make their case, Remainers usually draw on statistics that show a recent fall in net UK migration, especially from the EU. But the focus on overall migration numbers rather than on worker numbers leads to misleading conclusions. Migration trends are not the same as foreigner employment trends. Lots of people migrate for study, family and other non-working reasons.

Indeed, as recently pointed out by Spectator editor Fraser Nelson, the latest official employment data challenge the Brexit explanation for strains in the labour market. For a start, the number and share of all foreign workers in Britain has continued to grow, not fall, since the Brexit referendum. It has grown by half-a-million people, from 3.4million in June 2016 to 3.9million in March 2022. There is no overall decline in foreign workers in Britain. Indeed, the share of foreign workers within the UK workforce is now at a historic high of 12 per cent.

It is true that the steady pre-2016 growth in EU nationality workers has subsequently tailed off. However, there has been no absolute decline. Given the official figures are not seasonally adjusted, comparisons are best made at the same time each year. Since the latest figures are for March 2022, we will take March 2016 as the pre-referendum level, March 2020 as the pre-pandemic level and March 2021 as the post-Brexit transition figure. The number and workforce shares of EU workers were 2,144,000 and 6.8 per cent in March 2016; 2,415,000 and 7.3 per cent in March 2020; 2,197,000 and 6.8 per cent in March 2021; and 2,227,000 and 6.8 per cent in March 2022.

So this March there were still over 2.2million workers of EU nationality in the UK, representing the same share of the workforce as before the referendum. Indeed, this is 30,000 more EU workers than just after the transition period ended (when overall workforce numbers were deflated by the Covid lockdowns). And it is 83,000 more than just before the referendum. So much for the ‘effective exclusion of European migrant workers’.

The idea of an exodus of European workers following the Brexit vote is therefore a myth, so far at least. Indeed, since the referendum the total number of EU workers has consistently remained above where it stood at any time before the end of 2015. It is clear that European workers are missing in some of those well-publicised sectors, like hospitality and the care sector, but this cannot be attributed to an overall absence of EU workers. Maybe these particular shortages have more to do with the low wages and unappealing working conditions that are often on offer in those occupations? The EU-worker numbers show that we need to look closer to home to understand why the UK workforce is still 400,000 people smaller than in 2019.

Trade after Brexit

The Remainer thesis that declining exports impairs productivity growth was always erroneous – our productivity levels drive our export competitiveness, not the other way round. But there is also a lack of empirical evidence to suggest that Brexit has caused a decline in exports.

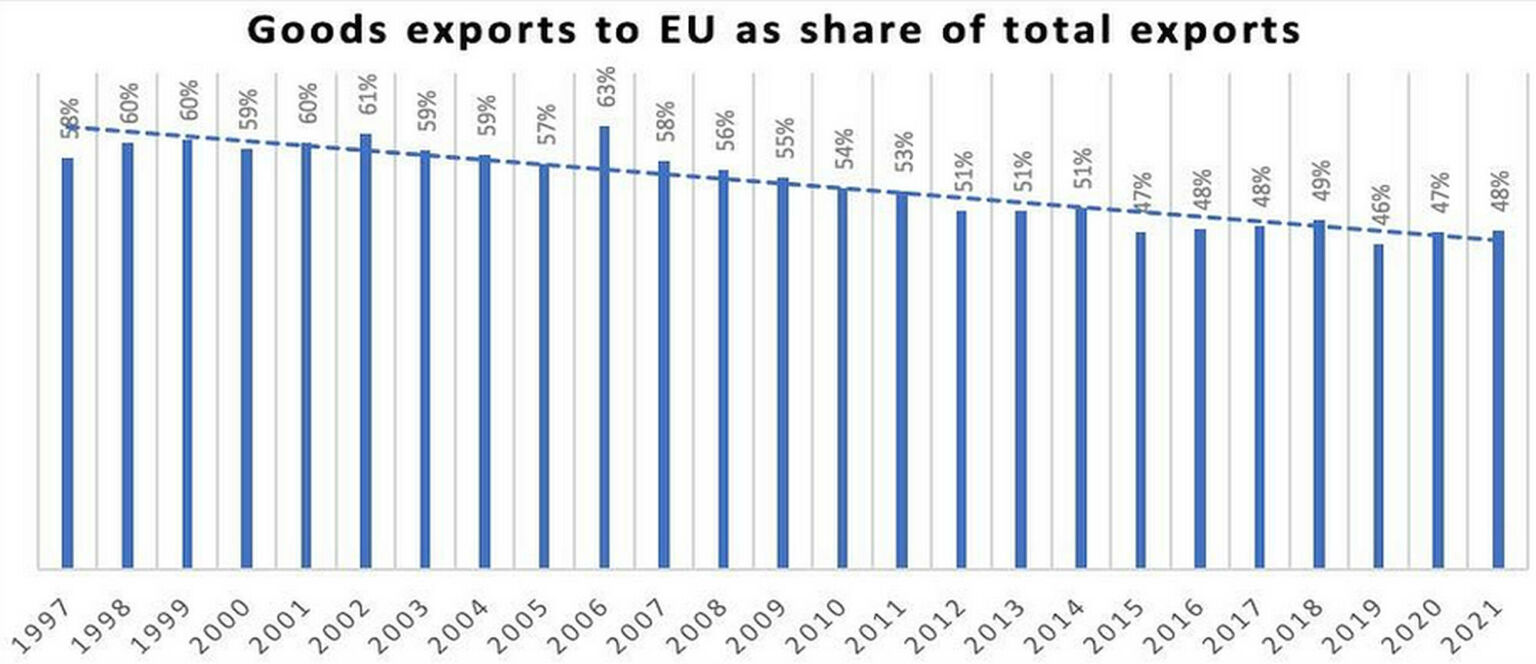

Since 2016, there has been no additional downturn in British exports to the EU compared with the rest of the world (see chart three). The bigger story is that Britain’s exporting capabilities since at least 1997 have been deteriorating, both in trade to the EU and to the rest of the world. This is consistent with Britain’s protracted decline in productivity, which impairs the average competitiveness of British goods on all world markets.

Indeed, the longer-term trend in British exports has been for the EU market to become relatively less important (see chart four). Brexit can’t be blamed for this decline as it began well before 2016. As I wrote in March 2017: ‘The EU peaked in its relative importance as an export market for British goods and services in 1992, just before the Single Market began. That peak market share was at about 60 per cent, up from 40 per cent when Britain joined the Common Market in 1973. Today, the share is back down to about 45 per cent, and has been falling pretty steadily since 2000.’

In fact, for goods only, the ONS’s figures in chart four confirm this decline, with goods exports to the EU falling as a share of total exports, from 59 per cent in 2000 to 48 per cent by 2016.

Strangely, the decline in the EU share of exports from the UK has slowed since the referendum and the end of the Brexit transition period. In the five years before 2016, the EU’s relative importance as a market for UK goods fell by five percentage points, while in the following five years it remained flat at 48 per cent. This development directly contradicts the idea that Brexit has distinctively, and disastrously, cut Britain out of a lucrative export market.

Leaving the Single Market has undoubtedly caused problems for businesses. But a far greater problem has been caused by the government’s failure to implement an economy-wide programme for investment and productivity growth. Indeed, since 2016, the government has repeatedly missed opportunities for economic renewal. People are right to be worried about the dismal state of the economy. But this stubborn Brexit excuse is distracting us from challenging the policies that are actually making matters worse.

Phil Mullan’ s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Emerald or Amazon (UK).

Main picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.