We are lurching from crisis to crisis

The UK economy is in a parlous state. And the government is pretending not to notice.

Last month, the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) announced that the British economy had marginally shrunk between February and March. An accompanying report showed business investment also falling, still nearly one-tenth below pre-pandemic levels and no higher than where it had been 15 years earlier before the financial crisis.

Apparently unphased, prime minister Boris Johnson responded to these grim bulletins by telling his cabinet that he felt ‘encouraged’ by the data. On the same day, he doubled down on his boosterism in a radio interview, where he claimed growth ‘will return very strongly in the next couple of years’. Meanwhile, his chancellor, Rishi Sunak, boasted that Britain’s quarterly growth was faster than that in the US, Germany and Italy.

These breezy responses to such bleak economic news were even more absurd given they came only a few days after the Bank of England had warned of ‘sharply’ slower growth on the horizon, and just before consumer-price inflation hit a 40-year high of nine per cent.

When the arrival of a ‘stagflationary’ slump – that is, fast-rising prices accompanied by sluggish or no economic growth – is greeted so positively by Britain’s leaders, we have surely reached a peak in political complacency. This tendency to evade the depth of our economic challenges, and to paint a picture of an economy doing pretty well considering the circumstances, has plagued the nation for far too long. It is an even larger problem for people’s livelihoods than the current spikes in consumer inflation, as bad as these are.

As we now know, the UK government’s unwarranted economic positivity was soon followed by an emergency announcement last week of £15 billion of additional financial support for households impacted by rising energy prices. Unfortunately, many of the early critical responses to Sunak’s statement have also failed to recognise the deeper issues that are being exposed by the cost-of-living crisis. Certainly, the Labour Party’s official reaction seemed more concerned with petty point-scoring than addressing the plan’s real limitations. Indeed, for shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves to claim that Labour is winning the ‘battle of ideas’, simply because Sunak is introducing a windfall tax on energy firms, is almost as delusional as Downing Street’s fantasies of a strong economy.

Some of the other responses were more valid. Yes, the government package was grudging and belated. Yes, as welcome as the extra handouts are to everyone struggling to pay their bills, they only dampen the financial pain and don’t remove it. Yes, more relief packages could well be needed if energy, food and other prices remain unusually high next year, as seems likely. And yes, such a large government intervention also exposes the myth that the Conservative Party believes in ‘free markets’ and tax-cutting.

But the real problem is the government’s continued failure to grasp that emergency assistance, while necessary for hard-pressed households, is an insufficient sticking plaster for an economy that is stuck in a long depression. The chancellor’s mini budget is yet another piece of short-termist pragmatism that shuns the more substantial tasks of reviving economic growth and of meeting the needs of the nation – such as building enough homes, modernising our transport infrastructure and ensuring a reliable and cheap supply of energy.

The cost-of-living crisis is not just a question of increasing prices. The reason the current inflation can even be considered a crisis is that the UK has not been creating enough wealth for people to afford these higher prices. And while the recent dislocations and disruptions caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine have had an impact, Whitehall still seems incapable of acknowledging that things were not going well economically both before the war and before the pandemic.

So far, most of the discussion about the cost-of-living crisis has focused on the ‘cost’ aspects. There is a general consensus here. Recent price hikes are attributed, partly, to the international supply-chain disruptions caused by the pandemic lockdowns and reopenings. For energy and food products, the war in Ukraine has been a significant driver of price increases. And when it comes to oil and gas specifically, the Net Zero agenda has led to extended shortfalls of corporate investment in exploration and production, thus curtailing supply. This has caused what some have dubbed ‘greenflation’.

It is not surprising that so much commentary has focused on the recent geopolitical drivers of inflation. But this tendency to fixate on the new has crowded out almost any appreciation of the longer-running ingredients of the cost-of-living pressures. Instead, we need to pay much more attention to the ‘of living’ aspect of the equation.

Why have the increased costs become so unbearable for so many households? Why is there so little capacity at an individual, business or societal level to cope with these price spikes? Without addressing these historical issues underlying the current hardship, we are likely to see a continuation of crisis management rather than a durable fix.

Look at income, not just prices

In time, in late 2022 or in 2023, depending on factors like the duration of the war in Ukraine and the impact of Beijing’s lockdowns, the annual rate of inflation will likely abate. But even as the current rapid pace of inflation eventually slows, households could still be struggling to meet those higher prices of essentials like food and energy. And even if those particular costs began to subside, many people would continue to live on the edge, until the next shock sends them deeper into privation. These scenarios reveal that today’s cost-of-living crisis is not just a product of price increases.

The weightier issue is this: we live and operate within an exhausted and overstretched economy that is less able than ever to provide the resources needed to cope with the jolts and blows that arise from time to time. Just one illustration of this atrophied condition, which happens to have a direct bearing on people’s ability to handle today’s rising prices, is the flatlining of incomes.

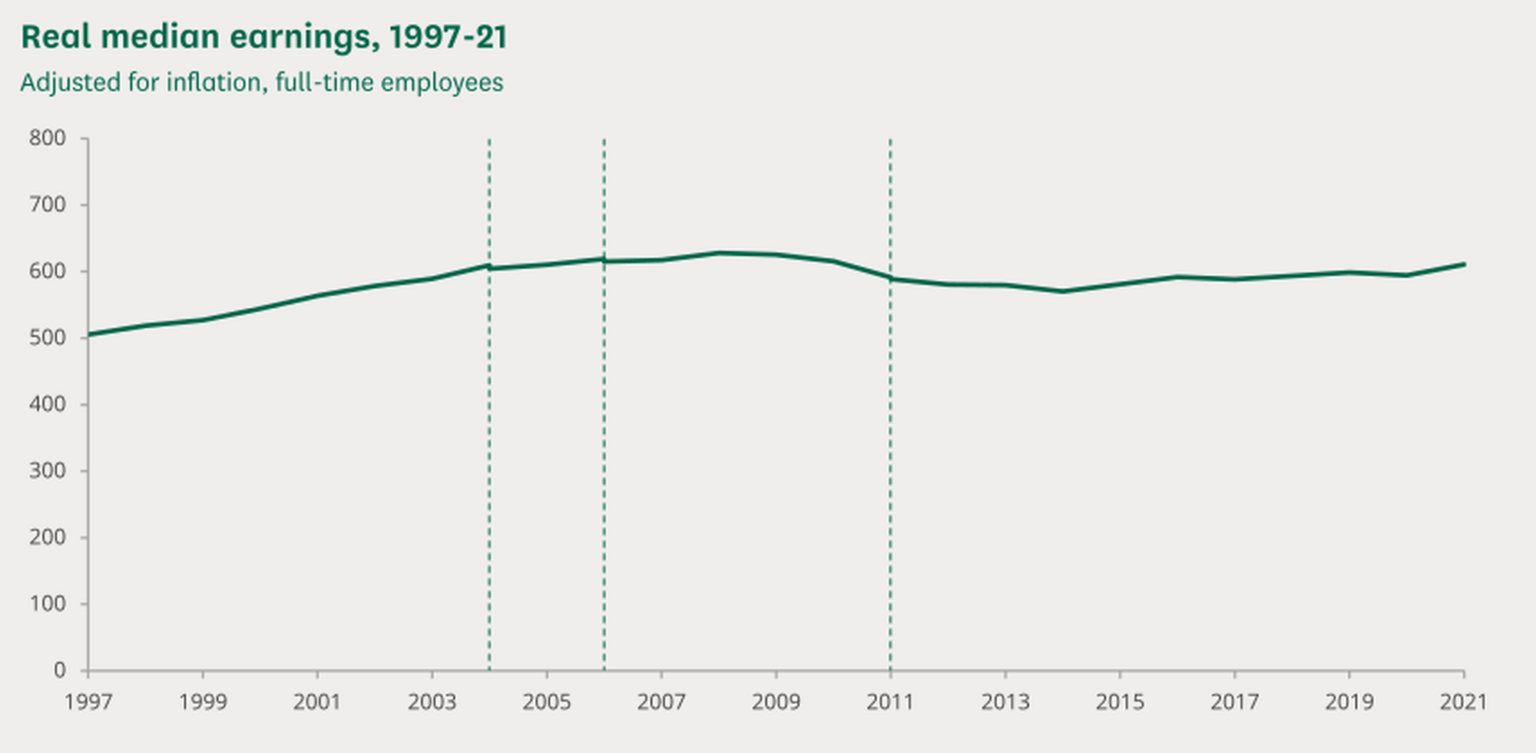

Earlier this year, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) warned of a record fall in living standards in 2022, as wages fail to keep up with rising prices. But this is just the tip of the iceberg following a long period of lacklustre income growth. Not so long ago, we expected living standards to double roughly every generation, but this prospect began to erode in the dying decades of the 20th century. Instead, we now have flatlining incomes. Indeed, after adjusting for inflation, average real wages in 2021 were still more than two per cent below where they had been before the financial crisis. We are living through the biggest squeeze in living standards since the Napoleonic Wars – and the main contributor is not inflation but depressed incomes. Wage growth between 2010 and 2020 is estimated to be the lowest over any 10-year peacetime period since the Battle of Waterloo.

We need a major shake-up

Britain’s economic prospects are determined by three principal factors.

First, the state of the economic fundamentals. This is encapsulated by the level of productivity – that is, the amount of goods and services that are being produced by people in a set time. Productivity underpins almost everything about our economic circumstances, from people’s living standards to the wealth available for public services and infrastructure.

Second is the state of our wealth reserves and other capabilities that people, businesses and government can call on, either to drive future prosperity or to provide resilience in the face of exogenous shocks – such as a financial crash, a pandemic or a war.

The third factor is the impact of government policies, and the extent to which these policies bolster or impede future growth.

In all three areas, Britain’s prospects look dire. Productivity growth has been dismal for a long time. And stalled productivity is at the root of our recent income stagnation. Despite the long-running discussion among economists about the ‘paradox’ or ‘puzzle’ of disappointing productivity in an age of more advanced technology, there is no puzzle here. It is the outcome of decades of lacklustre investment in innovation and in labour-saving technologies.

The UK also has few reserves or cushions to fall back on. More than anything, steadily rising indebtedness going back to the 1970s – combining personal, business and government borrowing – is a sign that we lack the self-generated resources we need to sustain economic expansion and provide for rising prosperity.

Debt used to be a means for funding corporate investment, or was used as an emergency respite in times of crisis. But in recent decades, borrowing has primarily become a substitute for insufficient wealth, reserves and resources to pay for current spending. Debt is now used mostly to finance consumption. And expanding debt has become the norm outside crisis periods, too. Since the 1980s, the UK has been borrowing from the future just to meet present expenditures. The cumulative effect of extreme indebtedness is that we now risk moving from a period where we drifted from one economic crisis to the next into one of almost permanent crisis.

For several decades, government policies have made all of these problems worse. Previously, economic policies were geared toward creating stronger economies, but in recent times this has changed. Successive governments going back to the late 1980s have emphasised the goal of stability in place of change. They have privileged the conservation of the status quo over potentially disruptive transformation.

Rather than embracing capitalism’s potential for pro-growth ‘creative destruction’, governments have got in the way of change. They have used a range of fiscal, procurement, regulatory and other policies to prop up incumbent businesses. Inadvertently, this then entrenches sluggish economic conditions. For instance, the burgeoning indebtedness that sustains the low-productivity zombie economy is not a spontaneous reaction to inadequate wealth creation. It has been enabled by official policies and practices intent on sustaining the status quo – in particular through the ultra-easy monetary policies of the Bank of England, which make borrowing easier and cheaper.

There is another way

Here’s the good news: because policy has played such a large role in creating the current crisis, this situation can be remedied. If the government reverses its pro-stability, preservationist stance, if it revokes those policies that reinforce sclerosis, it could instead help to rekindle the creative side of the creative-destructive process.

Historically, we know that crises can create opportunities for doing things differently, by shaking people and firms out of their complacency. However, there are no signs of this so far. For all the rhetoric about ‘building back better’ and ‘levelling up’, this government has continually put off boosting economic growth. It has not even set out a plan as to how it might achieve it.

Ministers understand that establishing the conditions for durable growth would be disruptive. They cling to the status quo because they fear how their constituents might respond to radical economic change. But disruption need not be painful and the public need not be feared.

Politicians need to radically rethink how they engage with the public in economic matters. There needs to be a nationwide conversation about how we take the difficult but necessary steps towards reviving economic dynamism. This is the only way we will be able secure future prosperity and progress – and be able to cope with whichever shocks come next.

Phil Mullan’ s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Emerald or Amazon (UK).

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.