The cost-of-living crisis has been decades in the making

Sustained underinvestment and rising borrowing have left Britain trapped in the Long Depression.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The soaring cost of living, aggravated now by the fallout from the war in Ukraine, is bringing dreadful difficulties and hardship for huge numbers of people in Britain. Even before anything like the full effects of the war can be predicted, the Resolution Foundation has warned that British people are facing the worst cost-of-living crisis since at least the 1970s. Over the next year it suggests the spending power of the average household could fall by £1,000 in real post-inflation terms, or by about four per cent.

It could get much worse. The conflict in eastern Europe, along with the associated sanctions imposed on Russia, is already driving the prices of energy, foodstuffs like wheat and grain, and other goods further beyond the previous highs caused by the disruptive effects of successive lockdowns. On top of the war and the pandemic, there are also the rocketing energy prices, brought about by decades of policy failures and a sustained lack of investment in energy production. And with the war triggering not just slower economic growth but potentially even another economic recession, lots of families could be facing extreme financial deprivation for a while yet.

Boris Johnson’s administration is now under increasing pressure to do something meaningful to help households financially through these grim times. Any government would be strained by having to react to these sharp increases in consumer and industrial prices. However, handling such challenges is not just a matter of political resolve – it also has a potent material component. Amid the government’s justified attention on the human and geopolitical effects of today’s European conflagration, it would be remiss for it once again to ignore the longer-term reasons why these exceptional price rises are leaving so many people in dire circumstances.

This is not the 1970s

Given the immediate focus on soaring energy prices as a key driver of increased household costs it is not surprising that many commentators are looking back to the oil-price shocks of the 1970s. Comparisons with the 1970s have helpfully identified some big differences between then and now. Some highlight, correctly, that the organised labour movement in Britain and other industrialised countries no longer exists with anything like the muscle it had then. As a result, although people could do with compensating wage increases in order to afford higher prices, this is unlikely to be achieved through the sort of collective action that characterised the 1970s (a few public-sector trade union strongholds aside).

Other commentators have highlighted, rather less convincingly, that we now have ‘independent’ central banks that have supposedly learnt from the 1970s and 1980s about how better to control inflation. However, in practice these central banks have been pumping liquidity into their economies for several decades now, triggering inflated prices and bubbles in various financial assets, from houses to equities. This experience doesn’t exactly instil confidence in their ability to resolve today’s cost-of-living pains.

This puts the onus for coping with today’s dramatically inflated consumer prices either on to people themselves, or on to the government as the people’s elected agent. This is where another significant difference with the 1970s becomes pertinent. The 1970s marked the start of the Long Depression that followed the postwar boom, whereas today we are half a century into that depression. We have had five decades of decay in wealth-creating capabilities. This means that compared to the 1970s there is much less slack for dealing with shocks, such as today’s hikes to household costs.

Of course, even with the slowdown in productivity growth that has occurred during the Long Depression, it is true that absolute economic output is more than double what it was in the 1970s. But relative to people’s expectations today, individuals and their governments have much less scope for managing economic shocks – whether it is a pandemic, a war nearby, a common-or-garden financial crash or recession, or today’s explosion in household-living costs. The stock of wealth available to handle particular adversities has been steadily depleted. After 50 years of productive atrophy, people and governments simply don’t have sufficient reserves of wealth to deal with these metaphorical bombshells. This turns them into much more severe and devastating events.

Because of the dearth of investment during the Long Depression, too many people haven’t had good enough jobs to accumulate their own stocks of wealth to withstand today’s cost surges. Meanwhile, governments have also had their income sources squeezed as economic growth lags, limiting their capacity to relieve people’s privation as their bills shoot up.

Ultimately, it is the wealth deficiencies arising from successive governments’ toleration of the Long Depression that underpins today’s predicament. Instead of being able to beat them, every economic challenge seems to develop into the next crisis. As Evening Standard columnist Martha Gill entreated, ‘We can’t go on running the economy by lurching from crisis to crisis’.

British society in depression has now gone well beyond living on the edge. We have become dependent on living off the future. Households, businesses and governments have all been forced to accrue substantial indebtedness in order to cover their expenditures. And even with all this borrowing, spending remains below what it should be for a prosperous well-functioning society. There is not enough business investment to bring about a better future, not enough government spending on core public services, and, for many people, not enough private means to enjoy a good standard of life.

This burgeoning indebtedness is not because a profligate, impudent culture has taken us over. It is because not enough new wealth is being created, and, as a result, borrowing has become the means by which we avoid unpleasant drops in living conditions. Debt has expanded because of the economy’s inability to generate the resources required to pay, directly or indirectly, for our needs and aspirations today. Meanwhile, especially over the past three decades, state practices have facilitated this accrual of debt, both through various government support initiatives and through the central bank’s easy-money policies.

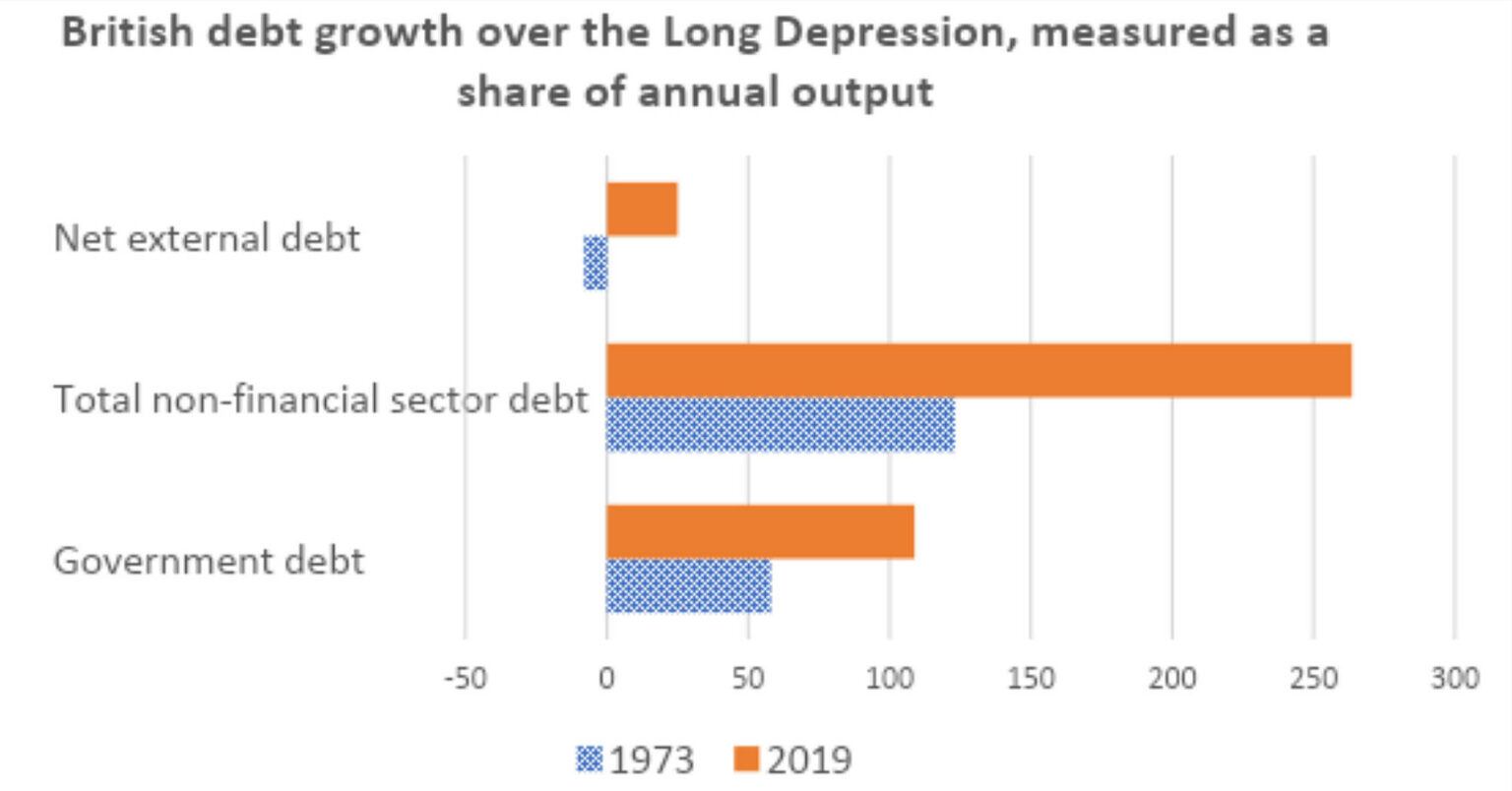

Indeed, a good illustration of how much more financially fragile and exposed we are today than in the 1970s is to see what’s happened to our collective state of indebtedness. In the graph below, there are three debt comparisons between the beginning of the Long Depression and today: Britain’s government debt; its total non-financial sector debt (that’s households, non-financial businesses, as well as the government); and its net external debt, summarising the country’s dependence on the rest of the world. All three reveal the greater mortgaging of the future.

In 1973, at the start of the Long Depression, Britain still retained more external assets – accumulated over more than a century of overseas investments – than it had liabilities to other countries. That net positive stock then measured about eight per cent of annual national output (gross domestic product). By the eve of the pandemic, nearly five decades later, Britain had long lost its international creditor status. It was then in hock to the rest of the world by about half a trillion pounds in net terms, the equivalent of a quarter of annual output.

Over the same period, the total indebtedness of the non-financial economy more than doubled to reach over two-and-a-half times annual output. Of that, the public-sector component grew by a similar rate, rising from a level of about half of gross national product to reach an amount equalling all the new value produced in Britain over one full year.

This expanding indebtedness confirms the absence of a cushion to withstand blows to economic production or to living standards. As a society, it is as if we are always balancing on the financial precipice until that next upset sends us tottering again. Each economic jolt, such as today’s ballooning prices, mutates into a bigger emergency because people and governments lack the spare resources to manage their way through the disruption.

Of course, those five decades of increasing borrowing also show there is no objective limit to how much debt is ‘too much’. But the higher are the debt burdens, the less room there is to weather whatever tests the future might bring. The more debt we have today, the more has to be spent simply servicing past borrowing, rather than being available for addressing present needs. It also makes it more difficult to find future lenders, except on onerous terms, which brings the potential of transforming a specific crisis into an even bigger one.

There is a solution

Rishi Sunak has faced calls, from within his party and beyond, to come up with more support for people and businesses to help them ride out this inflationary spike. Maybe he will relent in his spring statement and provide a bit more money, though probably not nearly enough to alleviate all the current and impending hardships. Or maybe he will resist, relying instead on his pledge to return the country to ‘sound finances’, after the skyrocketing public expenditure that accompanied the pandemic lockdowns.

While Sunak can be criticised for a lack of political will and imagination, the treasury is suffering from genuine material poverty. There are no rainy-day reserves he can call on as chancellor, putting him in an analogous position to many hard-pressed households. For example, Britain’s unemployment benefits system is the most paltry of all the advanced countries, not just because of successive mean-minded governments, but because Britain’s productivity – the output that each working person produces – has been among the slowest growing for many years. This represents an objective, tangible check on public spending.

The error Sunak and his predecessors at the treasury have made is to fail to acknowledge the depth of Britain’s economic decay. This means that he is blind to seeing that the solution to the treasury’s real financial constraints is not penny-pinching, but to help bring about an economic restructuring that can revolutionise the country’s wealth creation. The government needs to sponsor an escape from five long decades of depression. That’s the only way the government can build a genuinely resilient economy capable of generating the resources of wealth to surmount problems like today’s cost pressures.

The shock of the Covid-19 pandemic and the deficiencies it exposed in healthcare facilities, productive capacities and welfare support should have been a wake-up call to the government. We need economic renewal. Last October’s budget and three-year spending review was another missed opportunity. The question now facing the government is whether this war might at long last be the catalyst for a different approach.

Because until the government embarks on a wholesale plan for durable economic growth, dramas that could be withstood in prosperous times risk continuing to become serious and disruptive calamities. Without establishing much stronger productive capacities that can restore reserves of wealth, the country seems doomed to stumble from one crisis to the next.

Phil Mullan’s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Emerald or Amazon (UK).

Pictures by: Getty Images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.