This anti-sleaze crusade will not bring down the Tories

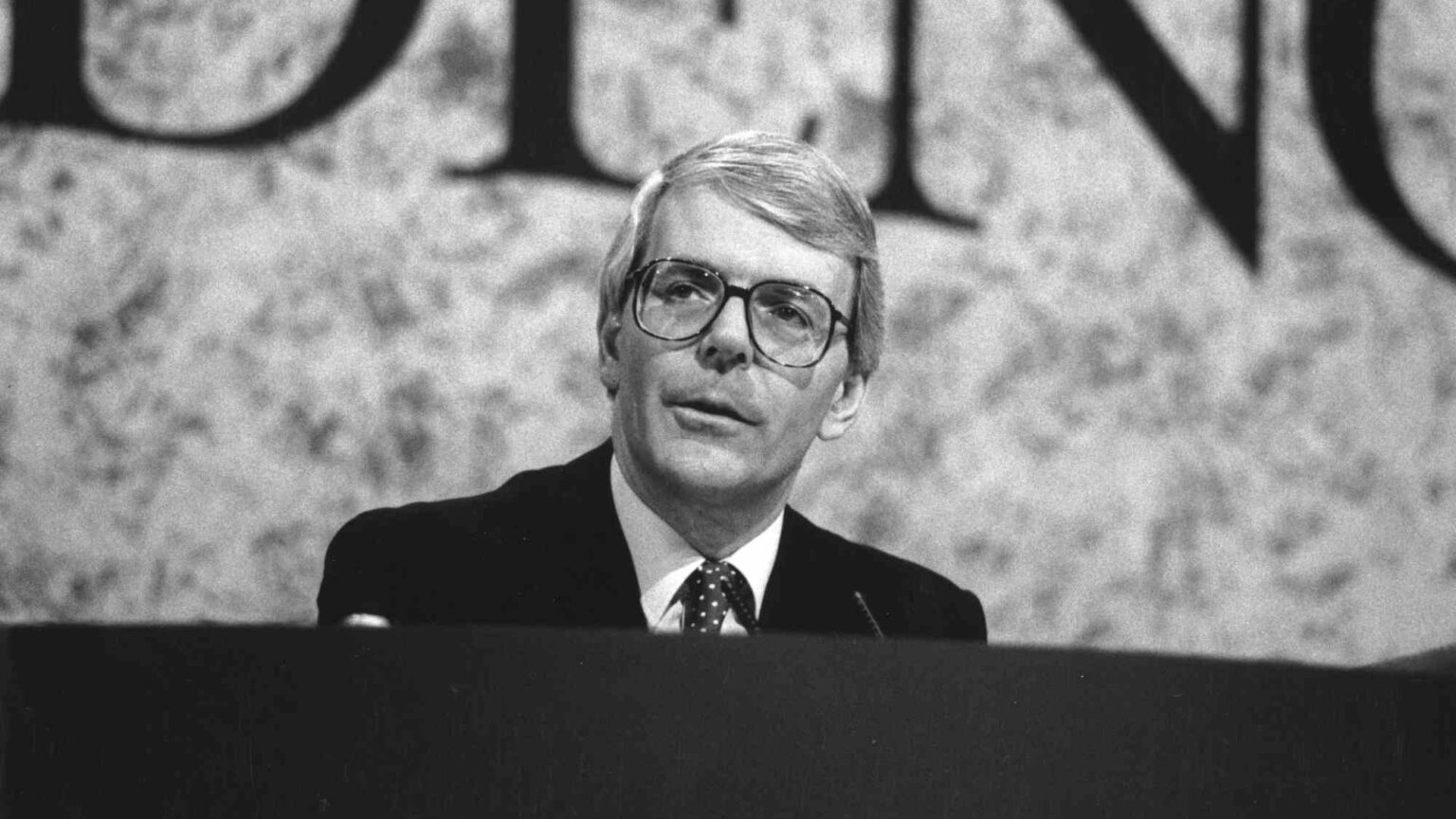

Labourites are drawing the wrong lessons from the John Major years.

Rarely has a period of British political history been as misremembered as the early to mid-1990s. Indeed, listening in recent weeks to Labourite pundits excitedly invoking the Tory ‘sleaze’ scandals of the John Major years, you could be forgiven for thinking the Major government really was brought low by the original cash-for-questions furore and a slew of extramarital affairs.

But that is as much a fantasy now as it was then. The truth is that Major’s Tories were already a busted flush long before the endless tales of infidelity earned the governing party its sleazy sobriquet.

It might seem odd to talk of Major’s Tories as ‘finished’ in the early 1990s, given the scale of their victory at the 1992 General Election, which they won with an unprecedented 14million votes. Yet that victory was as much a product of voters’ aversion to a strangely smug Labour Party – still clinging, Clause IV in hand, to the statist politics of the 1970s – as it was an endorsement of Major’s post-Thatcher Tories.

There was just very little fuel left in the Tories’ tank. They had already undertaken the brutal destruction of the postwar consensus, breaking apart the relationship between the state, the unions and employers by which capitalism had been managed for decades and replacing it with a more direct form of capitalist rule. And they had basked in that moment for much of the 1980s. But after that, what exactly was the point of the Tories?

Economic competence, mediated through the newly formed European Union, was the answer given at the time. That one source of ebbing authority was destroyed within just five months of Major’s 1992 election victory. On 16 September 1992, the pound collapsed and Britain was forced to withdraw from the exchange-rate mechanism (ERM), which was meant to pave the way for Britain’s adoption of what would become the euro. The exit from the ERM and the stock-market collapse, now known as ‘Black Wednesday’, effectively killed off the Tories as an electoral force. It undermined their economic authority and destroyed the pro-EU platform on which Major and others had staked their political careers.

Major later called Black Wednesday a ‘political and economic calamity’, which ‘unleashed havoc in the Conservative Party and changed the political landscape in Britain’. He was not far wrong. For it was this moment, and not the sleaze scandals that followed, that really did for the Tories for over a decade.

The polls tell this story well. In May, a few months before Black Wednesday, a MORI / Sunday Times poll put the Tories on 43 per cent and Labour on 38 per cent. In October, the same poll put the Tories on just 35 per cent while Labour were on 45 per cent. The Tories never recovered. From that point on, their poll rating only slipped further, at some points even dropping close to 20 per cent. (It’s interesting to note that the sleaze scandals made no difference to the parties’ poll ratings, with even the cash-for-questions affair having no noticeable impact on voters’ intentions.)

Without Europe, economic competence and the socialist enemy to ‘kill’, as Thatcher once put it, Major had no political vision to offer the UK. The closest he came to articulating one arrived in October 1993, when he called for a return to a ‘conservatism of a traditional kind’: ‘We must go back to basics and the Conservative Party will lead the country back to those basics right across the board: sound money, free trade, traditional teaching, respect for the family and the law.’

‘Back to basics’, as this vision came to be known, wasn’t meant to be a reference to personal or private morality. But that is how it was interpreted. And so, with every sex scandal, it became a cheap, often mirthful charge of hypocrisy to be delivered after every three-in-a-Tory-bed romp made the Red Top front-pages.

The sleazy ambience around Major’s Tories did not bring them down, however, as some now seem to suggest it did. It merely reinforced the already-existing sense that this was a politically and ideologically exhausted government, playing out its final, decadent days. Or as a Sun editorial put it in 1995, ‘This is a sleazy, dishonest administration led by a political pygmy’.

Yet, while the Tories certainly weren’t brought down by sleaze, what is true is that Labour and the media desperately tried to exploit it. Or, more accurately, they tried to use the notion of sleaze to conjure up the Tories not just as political opponents, but also as moral adversaries, a force of evil set against the emerging good of New Labour.

This was captured best in the case of then Tory MP and junior minister Neil Hamilton. In October 1994 the Guardian reported that Hamilton and another minister, Tim Smith, had received money from Harrods owner Mohamed Al-Fayed in return for asking questions on his behalf in the Commons. Smith stood down, but Hamilton, swearing his innocence, refused, and, ahead of the 1997 General Election, vowed to stand for re-election in his Cheshire constituency of Tatton.

Incredibly, Labour and the Lib Dems both agreed to stand down in order to allow war correspondent Martin Bell to stand as an independent ‘anti-corruption’ candidate.

Bell wasn’t a political figure, of course. He had no party and no policies. He was little more than a pompous, moralistic gesture stuffed into a white suit – the crass symbolism of which he had made famous while reporting on the war in Bosnia, before bringing it to the streets of Tatton.

Tatton made for a disturbing and prescient spectacle. Labour, the Lib Dems and the media – after all, Bell was a high-profile BBC reporter – had effectively set up the General Election for Tatton voters as a choice between good and evil, between the pure and the corrupt, the BBC man and the wicked Tory. Reports at the time noted that some Tatton electors were annoyed at what looked like an elite stitch-up. Some even felt they were being morally blackmailed.

Which in a sense they were. But then that is precisely the point of anti-sleaze campaigning. It moralises what should be a political conflict, presenting one side as tainted by evil – or by cash in brown envelopes – and the other as the good. It doesn’t clean up politics. It puts an end to politics, reducing all political debate to a question of good versus evil.

New Labour won the 1997 General Election and Bell won his seat, of course. But it is telling that Labour achieved its landslide win with fewer votes than Major’s Tories won in 1992. Turnout was down, too, and continued to fall throughout the New Labour years. Far from reinvigorating politics, the simple-minded sleaze-mongering merely turned many off it.

Today’s anti-sleaze crusade has the same characteristics. It is a desperate attempt to moralise politics and turn a future vote for the Tories into a source of shame. We are seeing, effectively, a revival of the Tatton election campaign writ large. Politics is being stripped of all substance and reduced to a simple moral choice – not between Labour and the Tories, but between good and evil. Hence the coercive tone of the countless broadsheet op-eds wondering if the latest Tory sleaze scandal might finally cause voters’ scales to fall from their eyes – perhaps this time, Guardianistas say over and again, voters will recognise the Tories for what they are: corrupt, immoral, a bit evil.

Playing the sleaze card doesn’t win elections or see off governments. And it certainly doesn’t address the very real problems generated by the private sector’s proximity to ministries of state. But it will cultivate apathy and anti-political cynicism – the very sentiments we all now associate with the New Labour period.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.