The dangers of guilt by ancestry

Cancelling people for the crimes of their families is absurd and dangerous.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Every Briton will have their own favourite woke moment from the past year. Who, for instance, could forget Edward Colston’s unscripted swim in Bristol harbour; the weird paramilitary parade by BLM London; or, a personal favourite, the BBC celebrating ‘largely peaceful protests’ in which 27 policemen and policewomen were injured? However, if you want to get at the dangerous potential of this unwinding cultural revolution, then look past these distractions to the more obscure but more telling business of ancestor cancellations.

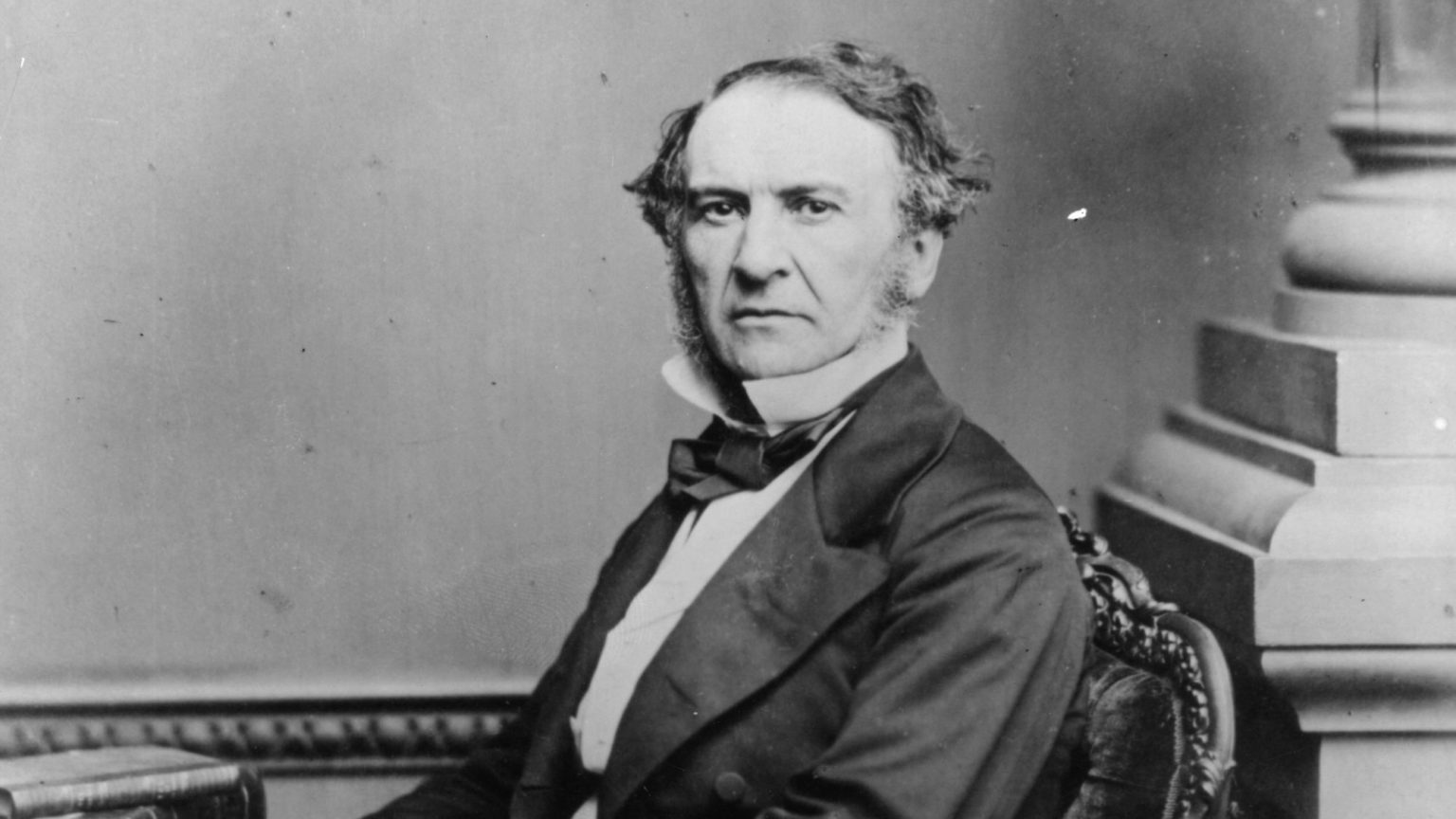

Ancestor cancellations are a novel form of abuse whereby we are made to accept responsibility for our ancestors’ misdemeanours. These cancellations grew out of talk of reparations for national crimes (some real, some imagined) and have moved quickly, over recent months, from entire peoples to lonely individuals. Take a simple British name-change. Liverpool University joined the social-justice wars by agreeing to rename Gladstone Hall, one of its residence blocks. It was encouraged to do so by an open letter from student activists in June 2020. ‘We cannot’, stated the letter, ‘facilitate normalising people like William Gladstone by naming our campus [sic] after them’.

An innocent outsider might admit to confusion here. William Gladstone was, by a meandering country mile, Britain’s most radical 19th-century prime minister. He was also from a Liverpool family (of Scottish origins). So surely Gladstone Hall was a geographically appropriate, progressive name for one of Britain’s more right-on universities? But there was a problem – upholding slavery. Not on the part of Gladstone himself – although he took the side of plantation interests in his maiden speech in May 1833, he was vocally anti-slavery through his subsequent political career. No, it was Gladstone’s slave-owning father who had offended the mandarins of woke. To be clear, Gladstone’s name had to be removed because of something that Gladstone senior had done.

Or take the poet Ted Hughes. In autumn last year, the British Library placed Hughes in a list of authors connected to slavery. Most of Hughes’ fans will have been surprised at this revelation. Was there some previously unnoticed allusion in Remains of Elmet, perhaps? Had a poor Cambodian been chained up in the Hughes’ garage? Nothing of the sort. But one of Hughes’ ancestors (Nicholas Ferrar, born 1592) had possibly been involved in the slave trade 300 years before Hughes was born. Nor was Hughes the only great writer to be punished by the British Library for the sins of his ancestors: Byron, Wilde and Orwell have also been found guilty by association.

There have, broadly speaking, been two methods employed against ancestor cancellations. The first has been to argue that the facts are wrong. For instance, Hughes’ biographer Jonathan Bate questioned whether Nicholas Ferrar was really related to Hughes. ‘Has anyone actually done a family tree?’, Bate asked. He also noted, one would have thought decisively, that Ferrar had not had any children.

The second strategy has been what could very loosely be called ‘the plea for context’: cue some the-past-is-a-foreign-country breast-beating about different values in a different age. This is a similar strategy to that used in the face of more conventional woke attacks on historical personalities. Gladstone, according to this approach, was an all-round decent fellow (‘look what he said about Ireland’), hence we should give him a pass (for the views of his father).

But both of these strategies skip past the most shocking feature of ancestor cancellations: the sheer dottiness of criticising people for things that other people have done; the unfairness of taking Jill to task for Jack’s failings. Our entire legal system, our religious system (in as much as it has survived) and our civil system is based on the principle of individual responsibility. You get praised and you get punished for what you do, not for what people connected to you have done. There is a lot to be said for this system. After all, when you do things wrong there is at least the hope of redemption: crime and punishment and, then, maybe, salvation. If you are paying for what others have done, there is no way out of the rat maze you are born into.

Of course, we all live with social and economic facts that shape our early lives. But generally speaking, individual responsibility holds in our society. This seems self-evident to most of us. We would not encourage our children to say ‘sorry’ for things that they had not done. Many of us would go further and teach our children to say ‘sorry’ only for what they do, not for who they are.

It is certainly striking how little space either the Common Law or the Roman Law countries have, at least since the rise of the communes, given to anything approaching collective punishments. Even at the height of the Second World War, the (somewhat provoked) British debated the destruction rained down on the general German population around Burke’s phrase ‘You cannot indict a whole nation’ – a phrase that Churchill trotted out in his public and private pronouncements.

There were some 20th-century Western attempts to make others pay for the guilt of relatives. The Soviets institutionalised the blacklisting of dissident family members: a tradition that has now been digitised by the Chinese Communist Party. Hitler created Sippenhaft, by which he was able legally to murder the relatives of his German enemies. But these were thankfully, in the West, brief aberrations.

As with much else in the woke universe it is tempting to characterise British attempts at blood-guilt as ridiculous misunderstandings, with relatively few real-world consequences. After all, we are talking here about a library spreadsheet and a hunk of Merseyside brick. Nothing to see, move along? But what is most alarming about ancestor attacks is how they show our own filters fraying and breaking. Yes, these stories are outrageous enough to be reported, and to be criticised by Gladstone and Hughes aficionados and by the shrill right. However, the outrage is not enough to force change: Liverpool University went ahead, rather smugly, with its decision to rename Gladstone Hall just last month; Ted Hughes was removed from the slavery database but the database itself (with other ancestry victims) remains.

Perhaps we would all be best advised to relax and climb back inside our Zoom bubbles for a few more months until sanity returns. But, no, it is much too serious for a supine turn. We are seeing in Britain a rapid dance on the part of public and private institutions, which either want to cause or to get ahead of change. Successful ancestor attacks on Gladstone, say, would have been unimaginable even five years ago. In two years, we’ll be saying the same thing about attacks on the living through their ancestors. The balance between the individual and society is tilting in the UK towards the collectivist chasm. As Hughes and Gladstone can tell you, there is precious little light down there.

Simon Young is a British author, freelance journalist and historian.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.