The case for a new world map

The Indo-Pacific is now at the centre of geopolitical conflict.

Maps shape how we view the world. ‘What a nation imagines on the map is a marker of what that nation considers important. This in turn shapes the decisions of leaders, the destiny of nations, strategy itself’, writes Rory Medcalf in Indo-Pacific Empire. Maps create a sense of shared geography between different nations, compelling cooperation and competition. Having the correct map, either on your wall or in your head, helps give the correct perspective of the world. As Robert Kaplan says in his book, Monsoon: ‘The right map provides a spatial view of world politics that can deduce future trends.’

Government plans to reshape British foreign policy post-Brexit, shifting its focus towards the Indo-Pacific, reflects a broader shift in focus. We need to discard the old Mercator projection map, which puts Europe and Africa at the centre of the world. In its place, on our walls and in our heads, we should have a Pacific-centric map of the world. Australia should be at the centre, with the Indian Ocean and Africa to its left, and the vast Pacific Ocean and the Americas to its right. This Pacific-centric map will allow us to better understand the great power struggles and economic forces that will define our world in the 21st century.

The origins of our current Mercator map lie in the European age of discovery. At some point around 1500 AD, European countries emerged as the most dynamic in the world. Their states possessed the greatest capacity, their economies were the most productive, their technology was the most effective, and their weapons were the most deadly. From this small corner of the Eurasian landmass, European armies spilled out across the world over the course of several hundred years and forged global empires. By the 19th century, save for a few remote outposts, the world became one knowable thing for the first time in history. In such a world, it made sense for Europe to occupy the centre of how we imagined it.

But even as power started to shift west to the United States, this map remained in our heads, despite some half-hearted attempts to create a US-centric map. By and large that was because the Mercator map still made sense to America.

On gaining independence, the young American republic saw itself as sitting on the western edge of the world, alongside the other newly liberated republics of Latin America. The old world, with its tyrant kings, petty squabbles, ancient hatreds and archaic class systems, sat across the Atlantic Ocean. America was both separate and connected to these powers. The US was ever wary of the old powers across the ocean to its east. And to its west, at least until the late 19th century, lay a vast wilderness on land, and an even vaster ocean.

Of course, that changed in the late 19th century, with America’s increased penetration of the Pacific. In 1898, the US annexed Hawaii and seized the Philippines from the crumbling Spanish Empire, making the republic very much a Pacific power. But even so, what lay over the vast Pacific was not the other world powers, but places other world powers went to conquer. America was merely claiming its own slice of the pie. In the American mind, the world was still centred in London, Paris and Berlin.

The First World War only compounded the perceived centrality of Europe. But then, the importance of the Pacific theatre in both the Second World War and subsequent Cold War further added to the sense of America as a Pacific power.

At the same time, the Cold War led to the creation of several subdivisions on the map for compartmentalising different theatres of engagement: Europe with its Iron Curtain; Southeast Asia, the frontline of insurgency; and the Middle East, a volatile region of shifting alliances.

Even with this regional compartmentalisation, it was still easy to imagine Europe as the centre of the world. Europe, after all, while the calmest theatre of the Cold War, was where the stakes were highest. America recognised early that without a democratic and prosperous Europe, its position in its competition with the Soviet Union would be fatally undermined. Europe, still at the centre of the map, was flanked by two superpowers – the Soviets to the east and Americans to the west.

Pacific thinking was still important in the Cold War, however. Much of the Pacific was considered key to containing Communism. At the same time, the rise of the Asian Tiger economies and California’s tech economy in Silicon Valley led to talk of the regions forming a ‘Pacific Rim’ in the 1980s and 1990s. Similarly, America’s strategic advantage was always explained by its unique position straddling two oceans.

Today we are entering a multi-polar world of competition between two great powers. Chiefly this is taken to mean competition and even conflict between the US and China. But the competition will not be simply defined as the incumbent US versus the Chinese newcomer.

Instead, new powers are emerging and old powers are re-entering the field. The US and China’s rivalry is just one part of this. The rise of China has disrupted whatever regional equilibrium existed before and the question is how other states react. To understand this, we need a Pacific-centric view of the world.

The first thing Europeans will notice is that Europe is now in the top-left corner. Europe will play almost no important role in the coming world of great power politics, except as a venue for negotiations and as a large consumer market. Placing it far from where the action will be is accurate.

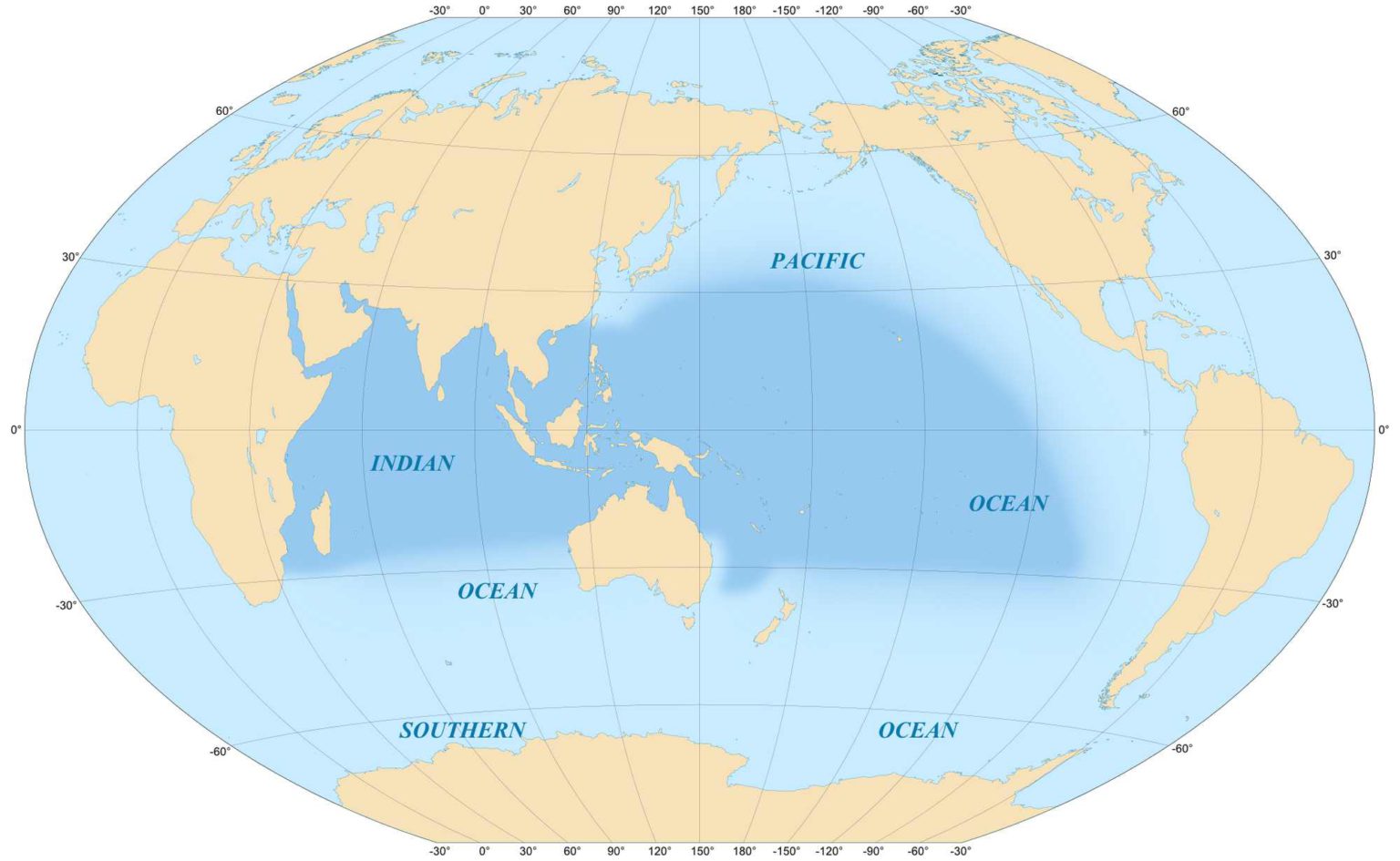

Instead, the new map shows the centre of the world to be two great lakes of water – the Indian Ocean in the west and the Pacific Ocean in the east. More accurately, the centre of the world is the pivot point between these two great lakes.

Of course, both of these regions are set to become ever more important on their own. The Pacific region will likely continue to be the home of the world’s most dynamic economies. Meanwhile, the Indian Ocean is home to some of the world’s future economic powerhouses. In its north-west corner sit the oil-exporting Arab states of the Persian Gulf. Further east are the rapidly growing and populous states of South Asia, including India, a likely future superpower.

But what is most important about the map is that it shows how the two oceans are connected, with the middle of the world where these two bodies of water meet. For it is here, where the Indian Ocean blends into the Pacific, that we have one of the world’s most important shipping lanes: the Malacca Strait. Through this narrow shipping lane, sandwiched between Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia, flows much of the world’s trade. The new map rightfully places this narrow strip at the centre of the world.

Almost all of East Asia’s energy imports come through this potential chokepoint, serving Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. Most importantly, China’s oil imports pass through the Malacca Strait. This creates something of a security dilemma for China – the strait could be easily blockaded during a conflict, which would starve China of energy. This problem has long been recognised by the Chinese Communist Party, with former president Hu Jintao calling it the ‘Malacca dilemma’.

Indeed, much of China’s foreign policy can be understood in terms of trying to get around this potential vulnerability. China’s relationship with Russia has often been frosty. But now China treats it as a great friend, largely due to its potential to supply energy from the north. Most importantly though, China’s Malacca fears are a key driver in its so-called Belt and Road Initiatives. One of the flagship projects of the BRI is the development of Gwadar, a port city in Pakistan’s restive Baloch region. China views lots of other countries in terms of their access to the Indian Ocean, including Myanmar, where there have been conflicts at the border.

A Pacific-centric map puts this Malacca Strait chokepoint front and centre. It shows the world to be composed of two vast lakes, divided by an archipelago which the great powers of the region must either work out how to bypass or control.

Seeing this on the map helps make sense of the South China Sea dispute. China is locked in a series of territorial disputes in the South China Sea with the Philippines and Vietnam, among others. China is accused of building artificial islands for military purposes. Whichever side is in the right, this conflict must be understood in terms of the pivot point between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. As Robert Kaplan notes in Asia’s Cauldron: ‘The South China Sea functions as the throat of the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans – the mass of connective tissue where global sea rotates coalesce.’ If China can control the South China Sea, it can control the Malacca and, by extension, these two great oceans.

Beyond the South China Sea dispute, the Pacific-centred map allows for a greater understanding of the general regional ambitions of China. Looking at the old map, China sits at the far eastern edge, with a few other states to its side. Viewed on the new map, China appears much more constrained, as part of a crowded theatre. To its east lies a rearming Japan, a hostile Taiwan and multiple US military bases. Further east sits the behemoth of the United States itself. China looks boxed in, prevented from bursting out into the vast expanse of the Pacific.

The new map also brings Australia and New Zealand into focus. These two states will, and indeed already are, key battle grounds in the new Cold War between China and the US. Under the old map, both nations are remote outposts, former colonies sitting awkwardly below Asia at the edge of the world. Under the new map, they are prizes to be won; sites for wars of influence and information between the new powers of the world.

Indeed, the new map brings to the fore a new alliance and understanding of the world: the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, of which the newly centred Australia is a part. This term was adopted by the United States in 2017 to define its new regional policy in the face of mounting tensions with China. According to Rory Medcalf, this new term breaks down the late-20th-century mental boundary that separated the Pacific and Indian oceans. It does away with ‘the once-useful but now outdated idea of the Asia-Pacific’.

By breaking down this barrier, this term unites states that are looking to collaborate in their bid to counter China’s rise, most notably India and Japan. Normally, the two nations, while both in Asia, are seen as occupying different regions – that is, unless we see the Indo-Pacific as one whole, as the new map forces us to do.

The Free and Open Indo-Pacific has also become shorthand to mean the informal alliance of India, Japan, Australia and the United States, the so-called quad of democracies. In a Pacific-centric map, these four powers all occupy strategic and important parts of the world, spread out across the two great bodies of water at its centre.

The Indo-Pacific is also the lens through which the US military views the world – forces based in Hawaii have recently been renamed the Indo-Pacific Command.

The world’s great powers clearly see the world in accordance with the Pacific-centric map. If we want to understand their motives, strategies and actions, it’s high time we started seeing things this way, too.

Tom Bailey is a financial writer. Follow him on Twitter: @tBaileyBailey.

Pictures by: Getty and Wikimedia Commons.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.