Long-read

Why free speech matters

From the Inquisition to cancel culture, censorship has always been the enemy of progress.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

To accompany the publication of his new book, Free Speech And Why It Matters, Andrew Doyle explains why censorship impoverishes us all.

Our scene begins on a lake of fire. Satan has been cast into Hell after a failed rebellion against God, and is fixed in chains along with his cohort of fallen angels. He assures his second-in-command, Beelzebub, that their defeat is only temporary, and that he intends to recover and continue the struggle against the ‘tyranny of heaven’. He breaks free and flies to dry land where he calls on his army to reassemble.

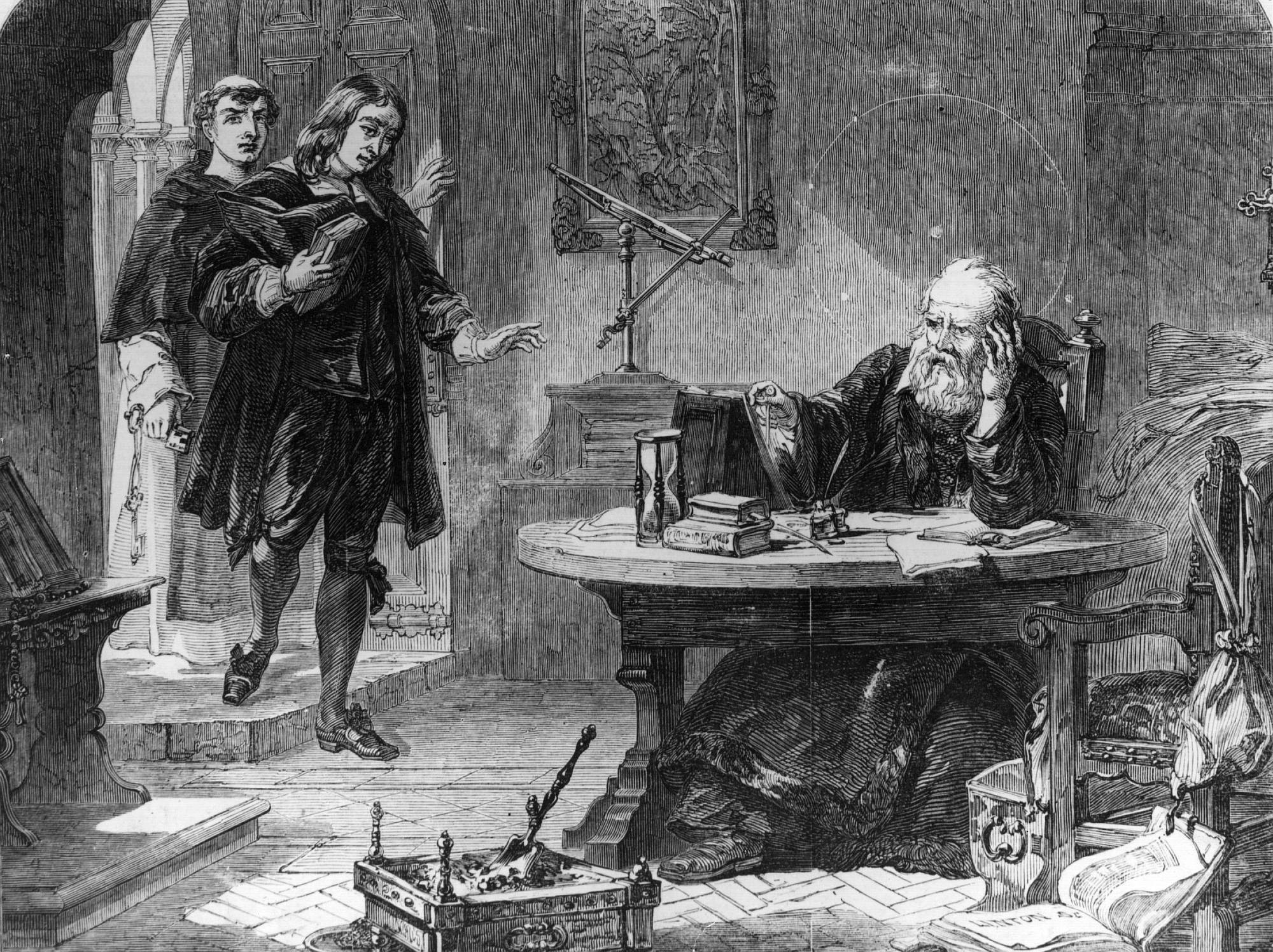

This is the dramatic opening of Paradise Lost (1667), John Milton’s epic poem about the fall of man. Amid Satan’s company of demons and counterfeit pagan gods there is an unexpected cameo which takes the form of a topical allusion. As Satan strides across the fiery landscape, Milton focuses our attention on his mighty stature by comparing his spear to ‘the tallest pine / Hewn on Norwegian hills’, and his shield to ‘the moon, whose orb / Through optic glass the Tuscan artist views’. This is Galileo, the only one of Milton’s contemporaries to be immortalised in Paradise Lost, here depicted with the recently invented telescope that he had adapted for the purposes of astronomical observation. Like Satan, he was cast out of favour for challenging the prevailing orthodoxies of his time – the evidence of his studies had persuaded him of the validity of the Copernican theory of the Earth’s motion around the Sun – but unlike Satan, Galileo was right.

Yet this flattering allusion was not the extent of their association. If Milton is to be believed, he met the ageing astronomer while on a trip to Italy in 1638. The reference appears in Areopagitica (1644), Milton’s counterblast to the Licensing Order of June 1643 which required all printed texts to be passed before a censor in advance of publication. According to Milton, he paid his visit while Galileo was under house arrest for ‘thinking in astronomy otherwise than the Franciscan and Dominican licensers thought’. Contrary to Voltaire’s writing on the subject, Galileo was not groaning away ‘in the dungeons of the Inquisition’, but was in fact living out his final days in his villa among the picturesque hills of Arcetri. It was here that he and Milton most likely met.

The villa still exists, just a 20-minute walk from the Arcetri Observatory. Fanciful visitors are likely to be drawn into vivid reveries of this meeting of two great minds; the young poet traversing the continent to expand his artistic and intellectual capacity, and the elderly astronomer confined to his home for his farsighted labours. From the perspective of the religious dogmatists of the time, Galileo’s words would not only have been considered offensive, but hateful, too. How might he have fared in today’s febrile climate, where feelings are prioritised over uncomfortable truths? If the phrase ‘hate speech’ had existed when Milton was writing his Areopagitica, it could well have been applied to the case of Galileo.

The Inquisition of today is not so savage. Our moral guardians have developed more civilised methods of satiating their bloodlust. Gone are the thumbscrews and the heated metal pincers, and in their place we see the vindictive forms of harassment and public shaming now known as ‘cancel culture’. The zeal is the same even if the methods are not. Anyone who has spent any time on social media will have witnessed the utter delight with which the practitioners of cancel culture bully and demonise those who have stepped beyond their locus of received wisdom. To take a prominent example, gender-critical feminists, who are concerned about women-only spaces for victims of domestic abuse, often have their views misrepresented as a form of heresy. For the crime of asking for an honest and civil discussion about sensitive issues, they are monstered as ‘hateful’ and ‘transphobic’ by a vocal and self-righteous minority of activists, some of whom feel no compunction in openly endorsing violence against them. Had these activists been alive during the time of Tomás de Torquemada, they would have been strapping these women to the rack.

Nor is this simply a problem of a few hot-headed fanatics. The notion that speech must be restricted for the sake of social cohesion is now a standard feature of contemporary policing. Perhaps the most striking image of this new mentality is one that went viral this week. The photograph depicts four officers from the Merseyside police, socially distanced but all facing the camera, standing next to a digital-advertisement van, which bears the slogan ‘Being offensive is an offence’. In this context, the depersonalising impact of their facemasks is all the more menacing. It feels less like a public-service announcement and more like a threat.

The image went viral because it seemed to encapsulate the inchmeal authoritarianism of our time, and the way in which our law enforcement agencies are now seemingly obsessed with monitoring our speech and punishing those who stray from the accepted script. ‘Being offensive is an offence’ is a mantra that would not have been out of place in the mouths of Galileo’s prosecutors. Critics of the police have been quick to point out that offence is entirely subjective, and so it would be impossible to legislate against this reality of everyday life. Following these complaints, the police deleted the tweet and issued a statement to clarify that being offensive ‘is not in itself an offence’.

Yet there are two important factors to this case that have not been widely considered. Firstly, the sign was not produced on a whim by a rogue officer with a Pharisee’s disposition. This was a professionally designed digital billboard which must have been approved in advance by numerous members of staff. There will have been meetings and discussions and a consensus would have been reached on the most appropriate wording. Even if the slogan has now been retracted, the fact that it materialised at all suggests something very sinister about the general mindset of those who are trained to enforce the law. After all, between 2014 and 2019, almost 120,000 ‘non-crime hate incidents’ were recorded by police forces in England and Wales. There have been a multitude of instances of police departments tweeting out warnings to the public that they could be arrested for speaking their minds. Irrespective of the legality, it is now standard police practice to monitor the speech of citizens.

But the more troubling aspect of this story is that, in a sense, the original slogan was correct. Every year in the UK, over 3,000 people are arrested for falling foul of the 2003 Communications Act by posting something online which causes offence. The legislation is explicit on this score; a prosecution will be secured if the material is deemed by a court to be ‘grossly offensive’. In Scotland, the SNP is persisting with its new Hate Crime Bill, which would mean that private conversations in the home would be subject to prosecution if they can be said to ‘stir up hatred’. Presently a 35-year-old man is facing the prospect of up to six months in prison for posting a derogatory tweet about Captain Sir Tom Moore. When the Merseyside police declared that ‘being offensive is an offence’, they had inadvertently let slip a terrible truth.

The principle of free speech has become difficult to defend because so many have accepted the false premise that defending the speech rights of unpleasant people amounts to an endorsement of their words. This is why there is little appetite among politicians to repeal existing ‘hate speech’ legislation included in the Public Order Act 1986 and the Communications Act 2003. In addition, the belief that public behaviour is dictated by mass-media consumption – a theory long discredited by six decades of research into ‘media effects’ – is now taken as an unquestionable truth. A profound distrust of free speech is a natural corollary of the new identity-obsessed conception of ‘social justice’ because it offers a fundamentally pessimistic view that sees words as violence and humanity as predominantly evil. This is why charges of ‘systemic racism’ are levelled at institutions even when the data clearly show that they are false, and why ‘fascists’ and ‘Nazis’ are seen in every shadow in spite of incontrovertible evidence that the UK is more tolerant and progressive than it has ever been.

This is not to suggest that those whose words cause offence are necessarily brave tellers of truth. In many cases, police investigations into ‘hate speech’ are directed at vile individuals who revel in causing distress. As someone who receives online abuse on a daily basis, I by no means approve of such behaviour. I support the rights of citizens to be abusive because I understand that the principle of free speech is too foundational to be surrendered to such objectionable people. They are entitled to express their hatred for the person they imagine me to be, and I have every right not to listen. This is the purpose of the ‘block’ function on social media; far from being a threat to free speech, choosing not to engage is to exercise one’s own freedom. It also means that there should be no need for tech giants to monitor content on their platforms. We can all decide for ourselves what we will and will not tolerate, and certainly do not require the intervention of corporations to act in loco parentis. Most of us would rather not be patronised.

This is a surprisingly common misconception, even among the most educated. Last week, I was the subject of online ire from a group of academics who were upset to find that I had blocked them. Given that I never block anyone for polite disagreement, a more self-reflective approach would have been to ask why it is that higher education has become so overrun with activists who would rather post abuse and assume bad faith than engage in adult discussion. As the author, Helen Pluckrose, pointed out to me, ‘it’s a worry when you can’t tell whether the person yelling at you is a 12-year-old whose parents need to take their Twitter account away, or a professor of sociology’. One academic at Oxford University was so angry with me that he complained directly to my publisher, presumably hoping that they might cancel my new book, Free Speech And Why It Matters.

The most depressing aspect of writing a book in defence of free speech in the current climate is that those who would benefit most from reading it almost certainly never will, unless it is to misrepresent its contents for ideological purposes. With that in mind, it is worth emphasising that the central argument of my book is for social liberalism and civil discourse, and is not to be taken as any form of support for bigotry or abuse. As I point out, the defence of freedom of speech is our most effective guarantee of equal rights for marginalised groups, and is the only way to see bad ideas successfully refuted. Not every heretic is a Galileo, speaking truths to a society not ready to hear them. But once we compromise on the principle of free speech, the Galileos of this world will suffer as much as the trolls.

This is why, in all of these difficult but necessary debates, my thoughts invariably return to that image of Milton and Galileo deep in conversation in a villa on the hills of Arcetri. Galileo had lost his sight by this point, and was worn out following his experiences of interrogation under continual threat of torture and his rejection by society. Is it too far-fetched to see in Galileo’s condition a premonition of Milton’s eventual fate? He too was to end his life blind and disgraced after barely escaping execution, in his case for supporting the republicans during the civil war. Denied the privilege of a place in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, Milton was instead buried in the chancel of St Giles Cripplegate in 1674, only to be mutilated in 1790 by souvenir-hunters who exhumed his body and sold his teeth, bones and locks of hair. The fate of heretics is rarely pleasant.

It certainly seems fitting that Milton and Galileo, both of whom famously lost so much for their honesty, might have enjoyed this fleeting encounter. The substance of their tête-à-tête will forever remain in the realms of fanciful speculation, but we can be certain that Galileo would have approved of Milton’s remark in Areopagitica that the freedom ‘to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience’ is the ultimate liberty.

Andrew Doyle is a comedian and spiked columnist. His new book, Free Speech And Why It Matters, is published by Constable. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Main image: ‘Galileo facing the Roman Inquisition’ (1857), by Cristiano Banti.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.