Why we need to resist road closures

Low-traffic neighbourhoods are harming the lives of local residents.

Roadblocks and low-traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) were introduced last year by councils across London, parts of Birmingham and other towns and cities across the UK, without notice or consultation. Councils say this decision to close off residential roads to through-traffic was taken to protect children and communities from selfish drivers using neighbourhoods as rat runs.

Many disagree, however. Take the Horrendous Hackney Road Closures (HHRC) group, which was formed in September last year by a group of young mothers and carers. With 7,000 members, it is now the largest anti-road closure group nationwide. Which is not surprising given that Hackney council’s road-closures programme is the most drastic anywhere in the UK.

Hackney council says drivers are a minority in the borough. It claims their views should therefore not be considered as valuable as other residents’ views. Council bosses have gone further and branded protesters as thugs and ‘birthers’ (born-and-bred East Londoners), who represent only a self-interested, bigoted minority.

‘The council and pro-LTN groups have been consistently demonising drivers and misrepresenting who we are’, says Josie Hughes, a member of HHRC. So in response, the HHRC has conducted a survey to find out a little more about its rapidly growing membership and why they choose to drive, and to dispel some of the myths about opponents of LTNs

More than 700 residents took part in the online survey, which was live throughout November and December last year. It reveals that the vast majority of members, at 66 per cent, are women. ‘We already knew from our Facebook group stats that women were the majority in every age category’, explains HHRC member Ruth Parkinson. ‘Clearly the issue of road closures is particularly hard-felt among women.’

The survey asked how important owning a car was to the life and wellbeing of respondents. Could they forfeit their car without it harming family life? Ninety-three per cent believed they could not, and that ‘giving up our car would be detrimental to family life’.

It was easy to see why so many of the mainly female respondents deemed the car indispensable. Many rely on cars for childcare, schooling, shopping and household tasks and, of course, holding down a job. That is not to mention those caring for elderly relatives or dealing with disabilities. Here are just a couple of the survey comments:

‘I’m a single mum, self-employed as a cleaner and I have to drive to my clients, due to all the necessary equipment I use. I also care for my disabled grandad who lives in another borough. I take him for medical appointments and take care of him. Without a car I simply would not be able to work, be a mum and a carer all at the same time.’

‘We are a large family of adults who share a car. I need access to the car as I do the household shopping, but also to take my elderly parents for appointments. Some of my extended family live locally but others live in different parts of London, and are not easy to get to on public transport. Our family is our support system, especially now with elderly relatives.‘

Still, politicians and policymakers say these closures are for people’s own benefit, whether they realise it or not. Given this attitude, it is no surprise politicians have no interest in engaging with the people in whose interests they are supposedly developing LTN schemes. Rather, they see it as their job to impose the schemes on people, so as to change or modify their behaviour. As the Department for Transport puts it, ‘Changes [brought about by LTNs] will help embed altered behaviours and demonstrate the positive effects of active travel’.

The undemocratic nature of the implementation of LTNs is striking, especially those rolled out during lockdown. But it is also unsurprising: councils know that if they put LTNs to a vote, they would likely be rejected. For instance, when Hackney residents were consulted in 2016, they rejected proposals to close several roads by almost 70 per cent. One of those most responsible for eventually closing Hackney roads, former councillor Jon Burke, even said he had no interest in consulting ‘rat-runners’.

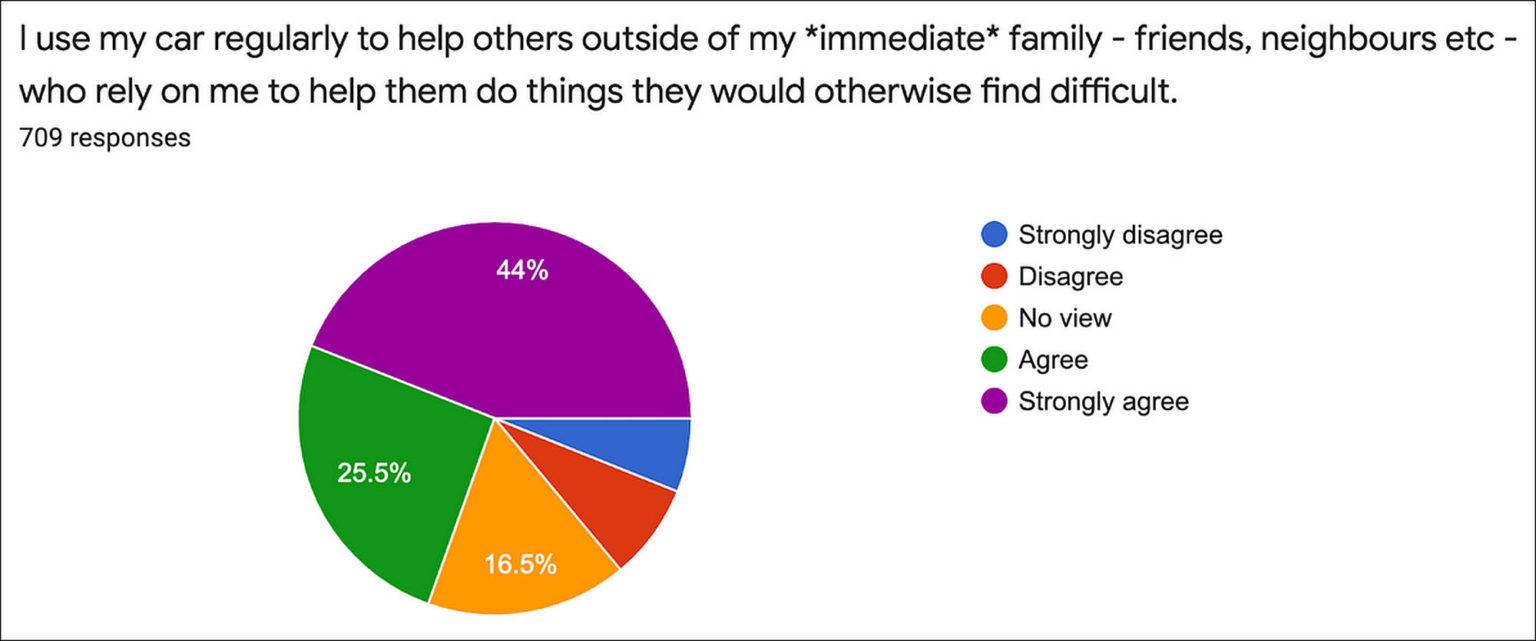

Rat-runners is an unhelpful pejorative that conceals the real reasons people use their cars. As the survey revealed, 79 per cent said they drive regularly to help others outside of their immediate family – elderly neighbours, friends etc – to do things they would otherwise find difficult.

‘We underestimate the usefulness of our cars as a community resource’, Ruth Parkinson tells me. ‘Many in our neighbourhood are held together by informal networks of helpers, carers, companions and shoppers. So often the car is an essential part of that equation.’

‘Over the years’, she continues, ‘I’ve used my car for work, to get myself and colleagues to and from work, for school and childcare drop-off, shopping, ferrying my mum around, taking neighbours to hospital, rescuing stranded teenagers, going to weddings, funerals, christenings, picking family or friends up from airports, train stations, to help friends move house. The list is endless.’

The council claims the roadblocks and LTNs are helping to discourage short ‘unnecessary’ car journeys of one or two kilometres, leaving the roads clear for those who most need them. The reality is quite the reverse. Quiet residential roads, and even school streets, have become gridlocked, sometimes for hours at a time.

Road closures have left many elderly and disabled residents stranded in their homes; massively increased journey times; left people struggling to get to work, hospital appointments, care visits; and have pushed many local businesses to the brink of failure.

The motorcar may have fallen out of favour with today’s political leaders, preoccupied with carbon-reduction targets and visions of a green utopia, but it still plays a hugely important role in the lives of many ordinary people. Cars bring pleasure, freedom and convenience to millions of us. To view them as little more than dangerous carbon-emitters driven by selfish, lazy rat-runners makes for narrow, divisive politics and short-sighted policy.

Niall Crowley is a writer based in London.

Picture by: Niall Crowley.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.